Somewhere close by, a woman is knitting a blanket to keep a person she’s never met warm. Someone else is hand-stitching a pillow to give a stranger a sense of comfort in their new home. A group of volunteers are pulling weeds, mowing grass and clearing debris. And another person is using their free time to answer phones and take out the trash.

On their own, these unassuming tasks appear to hold little significance. But together, they form just a piece of a large grassroots effort that is spurring on a new project in Franklinville – Operation Safe Haven.

A group of South Jersey volunteers has taken the growing trend of tiny houses to an abandoned campground in Franklinville and created something remarkable – a 277-acre retreat that provides veterans with 300-square-foot, fully furnished micro-homes. The hope is veterans can move into the new homes and focus on “getting squared away through various programs designed to give them the tools needed to adapt and overcome the struggles of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a place of true rest and relaxation,” says Pastor Donnie Davis of Franklinville’s Amazing Grace Ministries.

A group of South Jersey volunteers has taken the growing trend of tiny houses to an abandoned campground in Franklinville and created something remarkable – a 277-acre retreat that provides veterans with 300-square-foot, fully furnished micro-homes. The hope is veterans can move into the new homes and focus on “getting squared away through various programs designed to give them the tools needed to adapt and overcome the struggles of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a place of true rest and relaxation,” says Pastor Donnie Davis of Franklinville’s Amazing Grace Ministries.

Davis and Sgt. Ron Koller of the Gloucester County Prosecutor’s Office got the idea for the Operation Safe Haven back in January 2016. “Originally,” Davis says, “we looked into buying the campground to give it back to the community.”

But, as many successful grassroots projects do, things snowballed from there.

“I love those tiny house shows,” Davis says. “I wondered if we could use homes like that for vets and get them in a new space to help get their minds ‘right.’”

Davis knows all too well the realities of PTSD, or what he simply calls “stuff.” Davis served in the U.S. Air Force from 1993 to 1997 as a member of the Honor Guard, an elite unit that leads often somber ceremonies and special events all over the world. He worked in the White House and served at countless funerals at Arlington Cemetery, followed by five years working as a police officer in Prince George’s County, Maryland. The effects were life-altering, he says.

“Fifteen, 20 years later, it’s still hard to talk about,” says Davis, who prefers the term “stuff” to textbook jargon. “It’s hard for so many who are suffering to admit that something is wrong. It means you have a crack in the armor.”

And from his experience, Davis adds, most people in his situation don’t go to therapy.

“We don’t want to talk about it,” he says. “That’s why so many gravitate toward drugs and alcohol. It’s a way to cope and fight depression and the sleepless nights.”

The numbers don’t lie. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, approximately 11 to 20 percent of soldiers who served in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars have PTSD in a given year. That’s compared to about 12 percent of Gulf War veterans and as many as 30 percent of Vietnam veterans. And more than 20 percent of those who have PTSD struggle with substance abuse.

Operation Safe Haven gives them another option, says Davis.

“We’re not doctors,” Davis explains. “We’re just regular people trying to make things better for others. We’ve created this program to help people find their calm.”

The defining steps of the program are twofold: nature and service. Residents get their hands dirty learning how to garden, compost, tend to the chickens and care for the two horses on the property. They also grow their own food, both for themselves and for the program’s food pantry, which helps to feed 75 families in the local community. Veterans who participate are able to live in a tiny home and receive counseling for up to two years, free of charge. The goal is to help them prepare for a return to civilian life.

“You’ve got to get out of your current environment and circumstance,” Davis says. “When you give back, whether it’s to other police officers or to members of the community, you begin to find your self-worth. It’s amazing to see the progress that happens in people.”

David calls Operation Safe Haven, which currently has five tiny homes and plans for several more, an “eco-friendly, self-sustaining property” because of the work the nonprofit does and the food it grows. But it doesn’t take long to see that the services the organization provides are circling back to the veterans in unimaginable ways.

“People tell me we’re crazy and that we’re never going to make it if we don’t start charging people,” Davis says. “But then the phone rings with what we need. Things keep happening for us at just the right time, and it’s all thanks to regular people using their gifts to help.”

Some of those gifts are big. Like the $10,500 donation from Ida Gonzalez, the mother of fallen soldier Army Spc. Michael Gonzalez, which allowed Davis to build the very first tiny house on the property in his honor. Large organizations like Home Depot, BB&T, Wawa and GoFundMe have contributed to the program’s mission, and Comcast has committed to sending 500 volunteers to chip in this year.

But most of the gifts and help Operation Safe Haven receives are sent individually and small but, in true grassroots form, become impactful when stacked together. And Davis is eager to sing their praises.

There’s the $5 bill sent by a woman in memory of her late husband who suffered with PTSD, with a note penned in handwriting that Davis says, “looked just like my nana’s. That one always sticks with me.”

Davis also recalls the group of local homeschoolers who raked 20 bags of leaves. And then there’s the members of Sheet Metal Workers Local Union 19 and The JPC Group who rolled up their sleeves to clear the grounds that had been overgrown by nearly a decade of neglect. Another nearby campground, Hospitality Creek, donated picnic tables. A South Jersey mechanic donated a pickup truck. And when they needed a well, a local man donated a pump and installed it himself. People donate toothbrushes, knit blankets, sew pillows and volunteer their time.

“When mothers call me to say ‘thank you’ because they watched their kids go off to war and become an empty shell, but now they have life in them again…being able to see that you directly help people, that’s what this is really about,” Davis says.

Gonzalez says she knew she wanted to donate to Operation Safe Haven within minutes of walking the property.

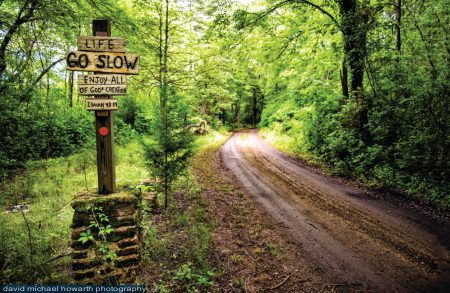

“It was amazing to me how peaceful the environment is,” she says. “I could see myself living there, it’s that nice. It’s so important for everybody to be aware of it.”

Despite Operation Safe Haven’s growing success, Davis is adamant about his refusal to cash in on the program.

“We’re not trying to make any money here. It’s important for people to know that 100 percent of donations go straight to the property.”

The campground isn’t just for veterans, Davis insists. It’s open to the entire community, and to prove that he reinstated the original campground name, Village Dock, a popular destination before it was abandoned years ago.

Davis hopes everyone feels welcome at the new site. “Come take a walk with us,” he says, encouraging anyone suffering from PTSD to stop by for a visit and everyone else to use their talents, whatever they might be, to keep the ripples moving.

“Everyone who steps foot on this property can sense that there is just something about this place,” Davis says. “It’s changing lives.”

Becoming a truly heavenly haven on earth. A very worthwhile cause and a beautiful place.