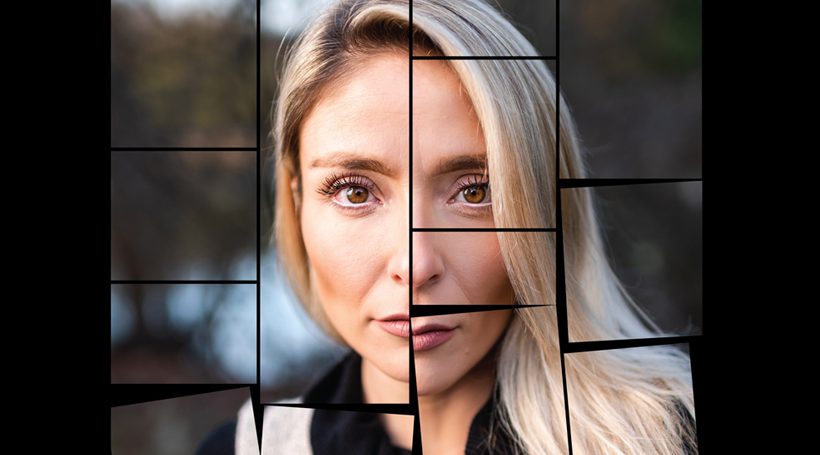

Photo: David Michael Howarth

Sarah Ripoli was just 6 when her abusive father killed her mother in their Medford home. Sheltered from the disturbing details, she went on to have a rather normal life. But all the while, something was missing: the complete story of what actually happened. It was something that always haunted her – until the day she decided to find out.

The sound is something Sarah Ripoli may never forget. She was a month shy of her 7th birthday when her father shot and killed her mother in their Medford home. It was 1999, but Sarah still vividly remembers those fateful minutes. It’s like an awful sound bite she can’t stop hearing.

“I just heard her scream, ‘Frank, no,’ and what sounded like two bricks slamming together,” recalls Ripoli, now 28.

“I just heard her scream, ‘Frank, no,’ and what sounded like two bricks slamming together,” recalls Ripoli, now 28.

It would be more than 2 decades before Ripoli would learn the lurid details of her parents’ marriage and the abuse her mother Brenda suffered at her father’s hands before he finally killed her. Those closest to Ripoli had always protected her from those facts, but a year ago she realized she needed to learn more.

“I shared with the followers of my fashion blog that I was a child of domestic violence and that my dad took my mom’s life,” Ripoli says. “That’s when all the other pieces of information started to fall into place.”

That’s when I knew I needed to find this journalist. She knew details nobody else knew. Who better to ask than the source?”

After seeing Ripoli’s post, her mom’s best friend reached out, asking if Sarah was interested in reading newspaper stories published at the time of the murder. That was from a time before most print articles were cached on Google, so they didn’t exist online.

“She sent me the hard copies of all these articles about my parents that were shielded from me,” says Ripoli, who now lives in Hoboken. “I am thankful for that now because it allowed me to live a normal life.”

Most eye-opening was a Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine piece from 2002 that chronicled the lurid details of Frank and Brenda’s 13-year marriage. From the start, Frank was abusive and controlling. He dominated his wife, forcing her to perform sex acts that he videotaped to use as blackmail, to ensure that she would never leave him. At the same time, he cheated on Brenda with other women during their marriage.

Ripoli learned that a superior court judge involved in the case described Frank as a poster boy for domestic violence. Also from the article, Ripoli discovered there was a letter found after Brenda’s death, in which her mother predicted her life ending at her husband’s hands.

“Maybe I was stupid for not leaving him… but I really believed that he would hurt or kill all of us,” her mother wrote. “I have therefore sacrificed my life to save [my daughter’s] life and the lives of my family members.”

But Brenda finally did leave him. She confided in a friend that his latest demand was too depraved – worse than any of the other sordid things he made her do. Though Ripoli wasn’t aware of her mother’s struggles, she does remember when her mother finally left, whisking Sarah away to her grandparents’ Florida vacation home.

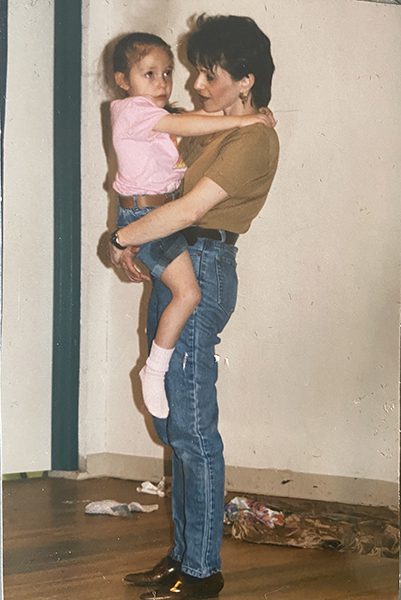

Sarah at 10

“In March of 1999, I was in first grade at Taunton Forge Elementary School in Medford,” she recalls. “My mom came to get me for early dismissal and we went straight to Florida. We didn’t have anything with us – we had to get clothes there.”

They didn’t stay long. Brenda’s lawyer urged her to return to New Jersey, that it would be important to do so to gain custody of her daughter. Brenda ultimately won, but was terrified to go back into their house to get her belongings. Frank assured the judge that his father would be there to guarantee Brenda’s safety.

“The people who were supposed to be supervising were a little girl and my father’s dad, who was hard of hearing and sound asleep on the couch,” Ripoli says. “My mom was going up and down the stairs bringing trash bags full of her things.” That was the last time Ripoli saw her mother. After shooting Brenda, Frank came downstairs and woke up his father. Ripoli remembers her grandfather following Frank up the stairs.

“I knew something wasn’t right,” Ripoli says. “My pop-pop came running down the stairs, saying ‘We have to get the baby out.’ I tried to run up the stairs but my dad blocked me and said my mother was resting.” She can recall then being in her grandfather’s car, where he said her mother was in heaven now. For the next 3 years, Ripoli alternated each week between her mother’s parents’ and her father’s parents’ homes. In 2002, Brenda’s parents, who lived in Mt. Laurel, received full custody, with Frank’s parents getting regular visitation rights.

Though Ripoli has those scattered memories from the day of the shooting, she didn’t know any of the ugly details from before or after. One story in particular, written by journalist Jan Hefler for the Philadelphia Inquirer, really hit her. It focused on what would happen to the 6-year-old child.

“That was me,” Ripoli says. “That’s when I knew I needed to find this journalist. She knew details nobody else knew. Who better to ask than the source? We connected, and it really helped me put all these pieces together. Jan gave me a 360 view of the whole story because she had interviewed everyone involved, including his first wife and co-workers.”

Over the years since writing about the murder, Hefler had often wondered if she’d ever hear from Ripoli.

“It had been one of my memorable stories,” Hefler says. “I’d had a conversation with a social worker about the story’s gory details and how I didn’t want to write anything that would hurt this young child. She said, ‘One day this young child is going to find you and ask you to fill in the gaps and help her understand what happened.’ So it was always in the back of my mind.”

So even though it was out of the blue and decades later, Hefler, now retired, was ready for the day that Ripoli finally reached out.

Sarah with her grandmother Ina Berman

“It was a relief that Sarah turned out to be a solid, decent human being,” Hefler says. “Sometimes people who are scarred are much more shy or bitter – people handle tragedy and trauma in so many different ways. This woman survived it really well. The system actually worked for her. The courts helped protect her, and her grandparents raised her to be such a fine young child who grew up to be a happy grown-up.”

Ripoli has loving memories of her mom Brenda’s intelligence and beautiful smile. “She was always teaching me things and we would play paper dolls and she would read to me a lot,” she says. “It was all happy memories with her. You don’t always remember what people said but you remember how they made you feel.”

Her recollections of her father are different. “I have very few memories, because I feel like he had very little involvement in my life,” she says. “I remember him always wanting to inflict fear. When I was 5 years old, he would force me to watch scary movies. I remember going to an amusement park and he forced me to hold my hands up on a roller coaster when I wanted to put them down.”

Sarah Ripoli today, photo: David Michael Howarth

She last spoke with her father when she was 15. “On Christmas Eve, his mom said, ‘Just wish him a Merry Christmas on the phone,’ even though I wasn’t allowed to,” Ripoli says. “I was on the phone with him for about a minute and I don’t remember how the conversation got to where it did, but he said, ‘She deserved it.’ That was the last time I ever spoke with him.”

Frank was in jail at the time. He had accepted a plea bargain to spare Ripoli the trauma of a nasty public trial, where graphic photos and videotapes would have been used as evidence. He pleaded guilty to a charge of aggravated manslaughter for an 18-year sentence. Frank has now been out of jail for more than 4 years.

“He has yet to try to contact me,” she says. “I don’t think he’s sorry at all.”

Discovering her story – her truth, she calls it – has changed her. Now she’s determined to share her experience as a means of empowering people to leave abusive relationships. Before the pandemic, she did public appearances, specifically reaching out to teens about dating violence and the important signs to recognize.

“I want them to know they are not alone and there’s nothing to be embarrassed about,” she says. “My whole life, I was embarrassed about being different and that this could have happened to me. It took me so long to realize I had nothing to do with this. You have to want to save yourself, and I hope I inspire people to do that.”

Last year Sarah started Angel Energy, an apparel company with a positive message. The line offers casual wear as well as a variety of T-shirts, sweats and other merchandise featuring the logo “Angel Energy.” One quarter of proceeds are donated to charities that fight domestic violence.

“My mom used to wear Angel perfume – it was her signature scent,” Ripoli says. “Angel Energy is having my mom be a part of it. She’s my own guardian angel. The message is using your guardian angel to fuel you to do good. It’s your decision, at the end of the day, to rise above.”