Courtesy of Edelman Fossil Park & Museum

At first glance, Edelman Fossil Park & Museum of Rowan University is just like other museums that introduce us to the world of dinosaurs, showing off a number of creatures reconstructed using fossils.

At first glance, Edelman Fossil Park & Museum of Rowan University is just like other museums that introduce us to the world of dinosaurs, showing off a number of creatures reconstructed using fossils.

But actually, it’s different.

“They lived here,” says Dr. Ken Lacovara, the fossil park’s founding executive director. “It’s a statistical near-certainty that a Mosasaur the size and shape of our 55-foot-long reconstruction was in that exact spot at some point. That level of authenticity – that’s what most other museums can’t provide for their audience.”

It’s been decades in the making, but what started as a little-known dig site has transformed into a state-of-the-art, one-of-a-kind museum. And sure, the museum is a paleontology-fanatic’s dream, but it also carries a lot of weight for anyone from South Jersey – whether you like dinosaurs or not.

“We are a very time-and-place-based museum,” Lacovara says. “Take the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Fabulous museum, but you could pick that museum up and put it in Connecticut, put it in Iowa, and it would be just fine. If you have all the same content, it would make sense in those locations. But not this place.”

The 123-acre site tells the story of the dinosaurs through a South Jersey lens. In the Dinosaur Coast exhibit, visitors will learn about dinosaurs that existed on the east coast of North America – just a bit west of the museum – at the end of the Cretaceous Period. The Monster Seas gallery is made up of creatures found on the property, including that Mosasaur. The events of the mass extinction are laid out as they would have been felt in Mantua Township – how long it took for the earthquake to hit, how long for the tsunami, all calculated for this location.

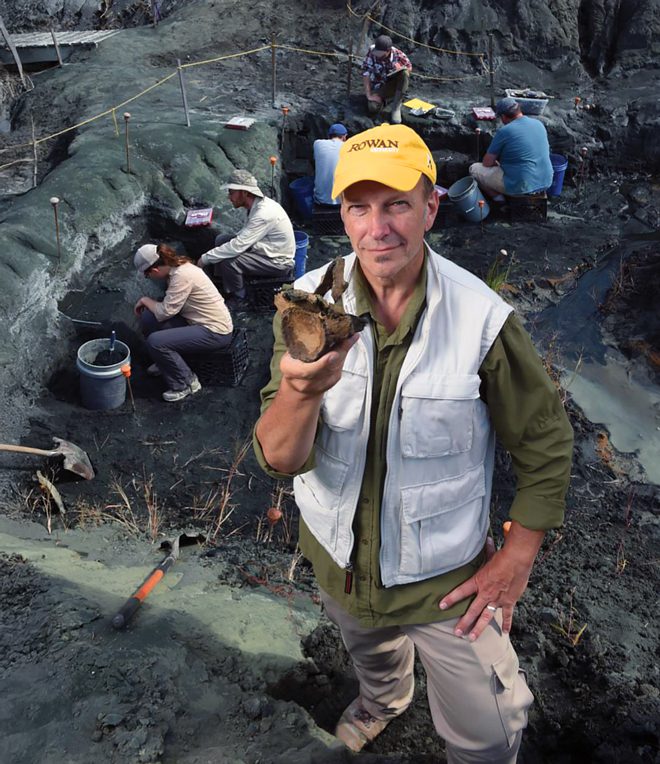

Dr. Ken Lacovera, Courtesy of Edelman Fossil Park & Museum

There is a children’s playground, live animal center, cafe, nature trails, museum store and bird watching. And, of course, the quarry that started it all – where you can actually dig for your own fossils.

Lacovara started excavating that quarry in 2003, digging for fossils with students while teaching in Philadelphia. It was before he traveled the world for his research, before he made history discovering the world’s most complete titanosaur skeleton in Patagonia (2005) and before he realized South Jersey’s impact on understanding the dinosaurs’ extinction.

But when the company who owned the quarry began to discuss selling the pit – and inevitably filling it in – in 2010, the South Jersey native took action.

“I marched into the Mantua Township Municipal building in my muddy green boots,” he says. “And I found Michelle Brewer, the Director of Economic Development for the township. I asked her if she knew what they had right here in her backyard. Miraculously, she jumped in my truck, and we drove over to the quarry. I explained the site to her and how amazing it was, and she saw the promise of it right away.”

The two realized the best way to save the site would be to get the community behind it. So they planned a public dig day, with the goal to show the community what Lacovara had shown Brewer. “We had no budget,” he says. “We sent out some emails, put a sign on the road to come dig with us on a Saturday morning. I was hoping maybe 75 people would show up. 1,500 people showed up. It was the moment I knew we had something really special.”

The two realized the best way to save the site would be to get the community behind it. So they planned a public dig day, with the goal to show the community what Lacovara had shown Brewer. “We had no budget,” he says. “We sent out some emails, put a sign on the road to come dig with us on a Saturday morning. I was hoping maybe 75 people would show up. 1,500 people showed up. It was the moment I knew we had something really special.”

The digs continued, as did talks for the original owners to sell the property. But the community’s pride in this unique resource grew year after year, prompting Lacovara to join his alma mater, Rowan University, in 2015 with hopes of keeping the site alive and eventually establishing a museum. He started Rowan’s School of Earth and Environment – where he served as dean for 9 years – and that same year, the university purchased the quarry.

But the catalyst for the museum becoming reality was a donation from two fellow Rowan University alumni. In 2016, Jean and Ric Edelman donated a $25 million gift, the second largest in the school’s history, to the museum project.

“The Edelmans have been a key part of this process and great partners,” says Lacovara. “It turns out that the three of us overlapped at Rowan. If you could go back in time and take those three students and tell them what they would do together 30-some years later, how in shock and how much disbelief they would have.”

In addition to supporting their former university and the community that raised them, Lacovara and the Edelmans see the museum as a way to get people, especially children, interested in science.

“I always call fossils the gateway drug to science,” Lacovara says. “At the museum, kids can find fossils with their own hands. We literally give them a free sample of science. We get them hooked on it.”

Courtesy of Edelman Fossil Park & Museum

It’s something Lacovara believes our society could use a little more of nowadays.

“We did the experiment of trying to run society without science – it’s called the Middle Ages,” he says. “We didn’t know where disease came from. We didn’t know where the sun went at night. We didn’t know where babies came from. Then we got science. And pretty soon, we have HBO.”

Not only is science bursting through the halls of the museum, but it’s also built into the literal foundation. The museum was constructed using sustainable practices, including building seven 250-foot geothermal wells underneath the parking lot as part of an energy-efficient heating and cooling system. That, paired with a power purchase agreement for renewable energy means the museum runs a carbon net zero operation.

“One of the first things I said to the architects was, ‘No fossil fuels at the fossil park.’” Lacovara says.

Implementing these practices is not just important, adds Lacovara, but it’s only right considering the message of hope and agency he hopes people take away from the museum’s final exhibit, which is an outline of today’s climate and biodiversity crises, and ways to slow and eventually stop them.

“We end with hope,” he says. “We want to show the visitor that no matter who you are, there are things you can do. There’s no time for despair. And I think the antidote to despair is agency. We’re trying to set that example. We’re trying to lead.”