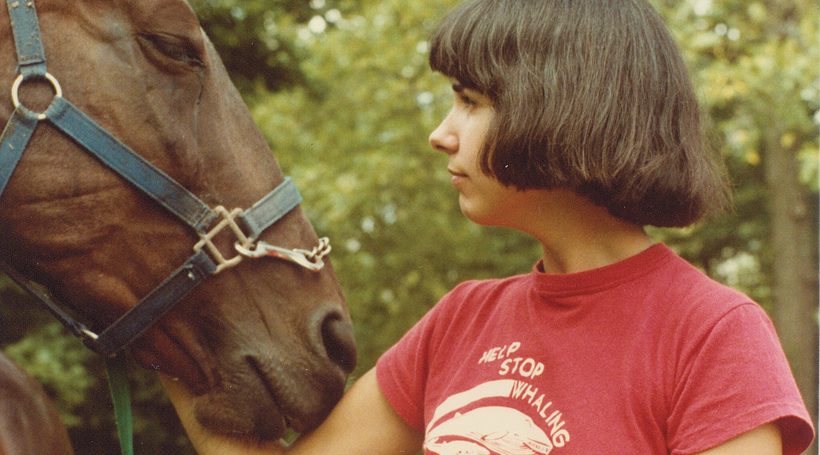

Cynthia Branigan with Gamal

Late in the summer of 1964, Atlantic City was bustling with attendees at the Democratic National Convention. Lyndon B. Johnson, who’d by then been president for nearly a whole year, was nominated for a full term in office. Cynthia Branigan, then 11 years old, was there – but her attention wasn’t on the politics.

Instead, what sticks in Branigan’s brain is the memory of standing at the end of Atlantic City’s Steel Pier watching a woman in a bathing suit and cap sitting on a horse with just a simple harness on its back. The horse ran up a steep ramp and then dove, 40 feet straight down, into a pool of water.

For nearly 5 decades, the diving horses were one of Atlantic City’s premiere attractions. People came from miles around to see the horses and their riders, the most famous of whom – Sonora Webster Carter – was blinded in a dive in 1931 and later became the subject of the Disney movie “Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken.” But by 1978, opposition from animal rights groups and plummeting visitor numbers in a struggling Atlantic City shut the show down.

Two years later, Branigan, then working in New York City at The Fund for Animals, got a phone call. The woman on the other end of the line told her Steel Pier had been sold, and the remaining diving horses were headed to auction. One, named Powderface, had already been sold at auction and was almost certainly destined for a slaughterhouse. Another, Shiloh, had been sold to a woman who planned to ride her. That left Gamal.

A few weeks later, at an auction in Burlington County, Branigan bid $2,600 for the horse who would change her life.

“The diving horse act was such a big part of Atlantic City for almost 50 years, but it is shocking to think that up until 1978 they were still doing it,” says Branigan, now 68. “It was one of those things that had always been there, and nobody stopped to think, ‘Wait a minute, is this right?’ For me, worse than the act is what happened afterward – the idea that those horses were just discarded.”

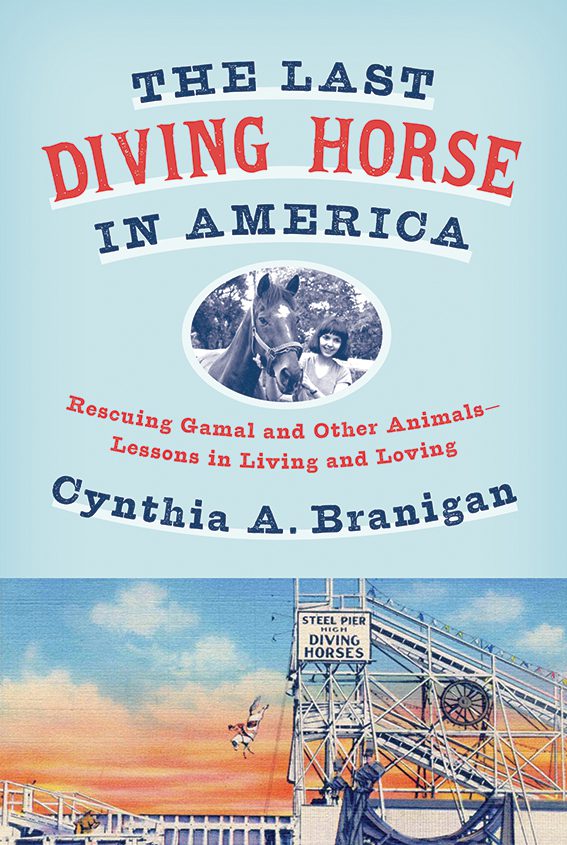

Gamal went to live on a nearby farm where, for most of the next decade, Branigan would care for him and a series of other rescued creatures for The Fund for Animals. After a career spent rescuing and caring for animals ranging from burros hoisted out of the Grand Canyon to retired racing greyhounds, Branigan wrote the story of her friendship with Gamal, and of Atlantic City’s diving horses, in her recently published memoir “The Last Diving Horse in America.”

“I started to realize that my life was really somewhat different from most people’s,” Branigan says. For years, she worked closely with The Fund for Animals founder Cleveland Amory, who she calls “the father of the modern animal protection movement.”

“The term ‘animal rights’ didn’t even exist when I started,” she says. “Later, another generation came along and started PETA and the Animal Liberation Front, but Cleveland Amory was way ahead.”

Author Cynthia Branigan

The book is as much a biography of Amory as it is the tale of William Frank “Doc” Carver, a 19th century Texas sharpshooter who toured the country performing in wild west shows with Buffalo Bill Cody before launching his own act: the diving horses.

In her book, Branigan gives a thorough history of “Doc” Carver and his successors, including riders Lorena Carver and Sonora Webster Carver, who brought the show to Atlantic City. It gave her the opportunity, she says, to clear up some misconceptions and tell parts of the story that have gone largely unreported.

“One person I felt has always disappeared from the story was Lorena,” Branigan says, “because it’s always been about Sonora. Most of what people know about the diving horses comes from her book, the movie…but Lorena was there before. She was one of the first divers. And her story, to me, is equally compelling, so I wanted to make sure I put in a bit about her. Now she has more than a footnote.”

Of course, it’s also the story of a horse – a very special horse – named Gamal. When she first laid eyes on him at the auction, Branigan writes, it was like love at first sight.

“The moment was not in slow motion, it was motionless, encompassing only my awareness of this glorious horse who, even then, I suspected would come to mean everything to me,” she recalls.

But as she soon discovered when they were safely back on the farm, Gamal was already in his 20s and a bit worse for wear. He needed a good diet, plenty of veterinary care and a gentle hand. He found all of those in Branigan, who bonded with the horse immediately.

The rest of the book details the 9 years she and Gamal spent together, getting to know each other and together befriending other rescued horses, dogs and more. Along the way, Branigan discovers her life’s purpose: to care for animals other people have forsaken or forgotten and to use her writing talent to help tell their stories.

When it came time to write the memoir, though, she knew it wasn’t just her story. “Cleveland Amory – I feel that a lot of people are forgetting who he was, and people are forgetting about Gamal. And that just couldn’t happen while I was alive,” she says. “I felt an obligation to him and his story.”

The lesson Branigan hopes readers walk away with is that animals – all of them – are deserving of compassion, and in need of the protection of people.

“Animals can be very powerful influences in our lives, but you have to be open to it,” she says. “Many people have pets, and they’re nice companions, but it doesn’t really change their lives. Some people regard them as dumb animals, or machines, or unfeeling creatures. It’s so wrong. I think most people in this country at least know you shouldn’t beat your dog or horse or starve it, but there’s more to it than that. You can relate to them on an even deeper level than simply humane treatment. Humane treatment is important, of course it is, but you’re cheating yourself if you think that’s enough.”

In August of 1989, Gamal, then well into his 30s, passed away and was buried on the peaceful South Jersey farm where he spent the last years of his life.

“I have visited the farm,” Branigan says. “Even now, when I’m up there I’ll take a turn and go down the road. I know it sounds crazy, but…I roll down the window and call out his name. He’s not dead, not to me. And I hope, with the book, he will come alive to a lot of people.