It’s an amazing sight: gold records and photos of him with music’s biggest stars mounted in perfect alignment on wall after wall, from room to room. As Leon Huff reminisces about the ones really close to his heart, it’s hard to pick a favorite.

It’s an amazing sight: gold records and photos of him with music’s biggest stars mounted in perfect alignment on wall after wall, from room to room. As Leon Huff reminisces about the ones really close to his heart, it’s hard to pick a favorite.

“I got this one not long ago,” he says, showing the framed certificate awarded by music-licensing agency BMI. “It recognizes eight million [radio] plays of ‘If You Don’t Know Me By Now.’”

Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes made the love song a hit in 1972. But Leon Huff wrote it, along with partner Kenneth “Kenny” Gamble, and together they formed the songwriting juggernaut that founded Philadelphia International Records in 1971. They rode the soul train for nearly two decades, fashioning a distinctive musical hybrid of R&B and pop that came to be known as TSOP – “The Sound of Philadelphia.”

Leon Huff is 72 now. He and wife Regina enjoy the good life in a magnificent Moorestown home, where Huff’s musical life is on display in tall walnut cases, all tastefully illuminated.

“For me as a musician,” he says, “there’s nothing like sitting in a studio and seeing musicians create your songs. That was the right time for Gamble and Huff. I have nothing but happy memories.”

There is no ego to Leon Huff. Plenty of pride, a humble appreciation of his partnership’s chapter in music history, but no ego. It has been quite a journey from a Camden row house, growing up in the 1940s and ’50s with a love of the piano instilled by his mother Beatrice, to his 2008 enshrinement with Kenny Gamble in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Upon first starting Philadelphia International Records, they built a one-stop music empire. The duo signed artists, wrote songs and relied on the sophisticated arrangements of producers Bobby Martin and Thom Bell. They brought it all in tune with a collection of musicians known as MFSB (as in Mother, Father, Sister, Brother) during recording sessions at Sigma Sound Studios.

The hit parade commenced in 1972 with The O’Jays and two songs from the same album – “Back Stabbers” and “Love Train.” Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes had a smash with “If You Don’t Know Me By Now.” So did Billy Paul with his Grammy-winning “Me and Mrs. Jones.” Motown Records singer Thelma Houston turned “Don’t Leave Me This Way” into a disco sensation that earned her a Grammy in 1978.

And that’s just a few high notes of the more than 3,000 songs over four decades. Gamble was the word man, Huff the music man. Their prodigious output yielded 15 gold singles and 22 gold albums.

Celebrity profiler Joel Brokaw is working on their biography, and there’s much to cover, like Huff’s days as a busy studio pianist in the early ’60s or playing for producer Phil Spector on The Ronettes’ “Baby, I Love You.” And you can’t leave out Gamble and Huff’s early days as independent producers who worked with artists like Dusty Springfield and Wilson Pickett, or when they composed the theme song for the TV show “Soul Train.” You also have to mention their breakthrough in 1967 when “Expressway to Your Heart” became a hit for white R&B group The Soul Survivors.

The musical duo in the early days of Philadelphia International Records

So what is Huff’s career highlight? He’s quiet for a moment, his mind on rewind through the decades. He and Gamble produced The Jacksons’ first two albums after their split with Motown Records in 1976, including writing the group’s hit single “Enjoy Yourself.”

That was huge. But, for Huff, not the milestone. It’s Elvis.In 1969, Presley wanted to record a version of “Only the Strong Survive,” the hit song they’d written for singer Jerry Butler the year before.

“His daughter Lisa Marie later told Gamble that Elvis played that song every day for I don’t know how long until he decided to record it,” Huff says. “When The King wants to do one of your songs, it doesn’t get much bigger.”

Although their label achieved a status that rivaled Motown Records, Huff says it wasn’t launched to make Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. lose sleep. It was frustration. They’d been independent producers trying to promote their artists to a balky local record industry in the late ’60s, a resistance that the pair read in shades of black and white.

“Trying to get radio airplay was tough,” Huff says. “Program directors would tell us, ‘Well, the record’s too black,’ or ‘It’s too R&B.’ The more they resisted us, the stronger we got. We had good songs that deserved to be heard.”

For youthful fans, Gamble and Huff’s synthesized sound had tremendous crossover appeal. The music filled dance floors and made people feel good. It transcended race in a way that society often couldn’t.

“For that moment, the song took over your soul. No one saw color, no one saw differences. They just felt happiness,” Huff says.

He ponders this while relaxing in his home office. He is soft-spoken and introspective, given to stroking his silver goatee while reflecting on life, and you can’t help but admire the photos that trace the evolution of the music man.

There’s teenage Leon on piano for the Dynaflows, his Camden doo-wop group. There’s record mogul Leon in flamboyant outfits and hats, loving that ’70s heyday, and there’s legendary Leon, dapper in tailored suits, accepting awards with Kenny Gamble.

“Me and Gamble stay in touch all the time,” he says, noting there are business decisions to make.

Gamble, a year younger and a couple of inches taller than his partner, is living in his native South Philly, still active and still committed to philanthropic neighborhood projects.

Huff loves him like a brother. He’s convinced that serendipitous forces led to their elevator meeting in 1964, when they worked for separate music companies in the Shubert Building, now the Merriam Theater. They discovered interests that sat them at the piano in Huff’s Camden house.

“It was meant to be. I tell Gamble that we always want to maintain the dignity of our legacy. Gamble is my man. He’s a very funny guy, a great conversationalist, so why would we ever ruin a relationship over something stupid?”

Huff enjoys these trips down memory lane, but they don’t define him. His isn’t the story of a vinyl dinosaur lost in the MP3 age. He’s on top of studio technology and promising groups. He’s on top of new music.

“I love that song ‘Happy’ – what a record,” he says, referring to Pharrell Williams’ feel-good smash. “That record has great vocal parts. It really pops that groove.”

Gamble and Huff hits are playing softly in the background. It’s an appropriate soundtrack, but there’s a particular poignancy, even sad symbolism, when you realize that’s the late Teddy Pendergrass baring the soul of “If You Don’t Know Me By Now.”

Music buffs who eulogized the passing of Philadelphia International’s happy days in the mid-’80s cited a variety of reasons – changing music tastes, crooners past their prime. But no one overlooked the tragic loss of Pendergrass, and Leon Huff will agree that when the singer’s car hit a tree on March 18, 1982, causing a paralyzing spinal-cord injury, it broke the heart of Gamble and Huff.

They had nurtured his career and transition to heartthrob solo artist in 1977. The duo was on a Jamaican getaway, writing tunes for the 32-year-old singer’s next album, when they learned of the Philly crash on TV.

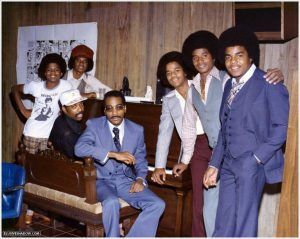

Huff and Gamble with The Jacksons

“Teddy had the whole package,” Huff says, preferring happier memories. “He looked good. He could sing – there was no other voice like Teddy’s. And what a sex symbol. I was at shows when I saw girls throw underwear at him. Women loved him.”

Pendergrass struggled to maintain his singing career and retired in 2006. He died of respiratory failure in January 2010, seven months after colon-cancer surgery. His accident intensified turmoil already simmering within Gamble and Huff. Music changes, hit parades wither. They were seeing the end of the rainbow.

“After Teddy’s accident,” Huff says, “me and Gamble talked about slowing down. We’d come out at sunset to go to the studio, and we’d stay up all night. We did it for years. By the time of Teddy’s accident, we’d peaked. I needed the rest. Gamble did too. I also was going through a divorce, and there was a lot of depression when the hits weren’t coming.”

Then he met Regina. She was Huff’s antidepressant. “She lifted the blues,” he says. He saw her on the dance floor of an SJ club, gyrating, ironically, to Pendergrass’ “Get Up, Get Down, Get Funky, Get Loose,” and Huff was smitten. “She danced right into my arms that night,” he says.

Huff likes his groove these days. It has been a busy 2014, which is the 50th anniversary of Gamble and Huff’s partnership. In February they signed a lucrative deal to complete Sony Music Entertainment’s acquisition of the entire Philadelphia International Records catalog – more than 3,000 master recordings – for global licensing and sales.

This past summer, they were honored at a New York City ceremony hosted by the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame/National Academy of Popular Music. The organization, which inducted the duo in 1995, gave them the Johnny Mercer Award, a songwriting prize awarded last year to Elton John and Bernie Taupin.

This past summer, they were honored at a New York City ceremony hosted by the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame/National Academy of Popular Music. The organization, which inducted the duo in 1995, gave them the Johnny Mercer Award, a songwriting prize awarded last year to Elton John and Bernie Taupin.

Heady stuff indeed. But you’re also obliged to ask Leon Huff about some discordant notes in his career. Five years ago the founders of The O’Jays, Eddie Levert and Walter Williams, sued Gamble and Huff, claiming the group was owed $47,000 in royalties. The songwriters contested mightily but settled out of court.

It still irks Huff. Tell him you don’t like a song arrangement. Tell him you don’t even like the song. But accuse him of keeping royalties – that really makes his needle skip.

“Gamble and Huff never – never! – took no one’s royalties,” he says. “But we still had to defend our innocence, which cost a lot of money. I never took royalties, I never took melodies. Me and Gamble never copped somebody’s groove. We were too busy figuring out our own.”

He is, however, bothered that once-tight ties have been frayed, perhaps forever. Huff smiles at the irony that, just his luck, Regina loves The O’Jays and coaxed him into seeing an Atlantic City performance two years ago.

“She always wants to take me to see them. So where do you think they seat us? Right up front,” Huff says. “The group brought me up on the stage. We hugged. I don’t hold a grudge. But could we ever work again? I don’t know.”

Life can’t always be a happy tune. But when all is said and done, he’s confident history will show that Gamble and Huff were a great musical pairing.

“I’d like to think our legacy is that people had a chance to experience the soul of Gamble and Huff, and listen and dance to some of the greatest music ever presented,” he says. “I’d like to think Philadelphia International Records contributed music to lift the soul. That’s all we wanted to do.”