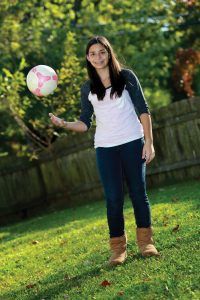

Vicki Zarifis worries about her twin girls, Alexandra and Filianna, now 14. She has the usual parental concerns, but when it comes to Alex, there are the added stressors of what and when her daughter is eating.

“When we sat down to eat, I was always aware of Alex,” says the Cherry Hill mom. “After dinner she’d do her homework, but was she heading to the fridge or cabinets? Was she putting something in her mouth?”

Filianna is a picky eater, says Vicki, who never had weight issues. Alex, on the other hand, had the same problem pop up again and again as the scale climbed and climbed.

“Alexandra liked food, especially pasta and bread. Even formula – she drank it too fast. Her twin never finished the bottle. I always wanted Alex to eat slower. She always wanted more,” says Vicki. “Around 12, she started to gain more weight. She got up to 147 pounds by age 13.”

It wasn’t just her 5-foot-2-inch daughter’s health or appearance that troubled Vicki, but what her child would think down the line.

“If she was 18 and obese, would she say to me, ‘Why didn’t you try to help me?’ How will this affect her health in her 30s and 40s? It was always in the back of my head,” says Vicki. “Maybe I wasn’t doing enough. I felt like, at age 10, 11, 12, it’s my responsibility to do something.”

As with an adult, a child’s unhealthy weight can come from a toxic mix of genetics, choices and lifestyle. Adults have autonomy over two of the three, including what they put in their mouths and when they hit the gym. But since kids typically rely on their parents for meals and activities, are parents responsible for their overweight kids? It’s a question that has piqued the interest of all involved in the child-obesity issue, from health advocates to medical professionals.

“This is more about accepting responsibility,” says Tim Kerrihard, president and CEO of YMCA of Burlington and Camden Counties. “Yes, parents have the primary responsibility for their children’s wellbeing, but they are not the only ones who are accountable. It’s the village idea that we all must adopt. We all have a role to play – parents, teachers, school districts, elected officials, corporations, our towns and neighborhoods; the list goes on and on.”

Kerrihard, like pediatrician Lori Feldman-Winter, MD, sees parental responsibility for obesity as a complex issue that is riddled with chasms. Kerrihard says there are gaps in areas like nutritional knowledge and access to healthy foods that parents alone cannot fill. Feldman-Winter says self-awareness is one of the more distressing disparities she has faced as head of adolescent medicine at Cooper University Health Care.

“One of the big issues in parental guidance, more likely than not, is the parents have the same problems. The parents have many of the same behaviors,” says the professor of pediatrics. “As surprising as it sounds, parents are looking at their kid and not thinking about their own weight and health.”

About 25 percent of high schoolers in new Jersey are overweight or obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For kids ages 2 through 5, that rate jumps to just over 34 percent. Those numbers are not that surprising considering nearly 85% percent of adults in New Jersey are overweight or obese, and most children learn eating habits in their homes.

Habits played a huge part in Alex’s weight gain.

Her late-night snacking and second helpings made the scale’s needle swing forever to the right, even though she played soccer, says Vicki. She began to wonder if it was just genetics. After all, Vicki says, her mother and grandfather struggled with their weight.

Now 130 pounds, Alex Zarifis has gone from the “obese” 95th percentile to the “healthy” 83rd percentile on the BMI calculator

To help her daughter, Vicki began serving salads before dinner, keeping Alex’s trigger foods out of the house and having fish more often. It also helped that Alex took charge of her diet. Now 130 pounds, Alex has gone from the “obese” 95th percentile to the “healthy” 83rd percentile on the Body Mass Index (BMI) calculator.

Those familiar with the BMI calculator for adults will find percentiles a foreign concept. For adults, BMI calculations only require height and weight. For children, age and gender are needed, so their numbers can be compared within the same sex and age range. Much like adult BMIs, kids’ BMI percentiles are grouped into the categories “underweight,” “healthy,” “overweight” and “obese.” Children and teens in the 95th and above percentile or higher are considered obese.

“We start to calculate BMIs at age 2,” says Feldman-Winter. “That said, we know the obesity epidemic has increased in the number of children and adults, and we are seeing it spread to infants and toddlers under age 2. We begin the obesity epidemic in infancy with overfeeding. It grows into eating habits. It’s hard to break that cycle.”

The CDC cites several red flags that can lead to childhood obesity. The usual suspects are there, from downing surgery drinks and less-than-nutritional foods to spending too much time using electronics, but so is breastfeeding – or the lack of it. There is a 15 to 30 percent reduction in adolescent and adult obesity rates if a mother breastfeeds, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. The CDC has floated the idea that breastfeeding mothers may chose a healthier lifestyle, but it also determined there may be biological mechanism at work, such as a higher insulin concentration from formula feedings.

“Bottle-feeding increases the epidemic, because it’s easy to overfeed from a bottle,” says Feldman-Winter, citing one of the CDC’s findings that hunger cues are more easily met during breastfeeding.

It is hard to get away from the fact parents instill tendencies that last a lifetime, but at some point, a child is exposed to other ideas. They will go to school, visit friends’ homes and eat at the mall food court. Kerrihard’s “it takes a village” belief has filtered to school districts and prompted the YMCA to propose a number of wellness initiatives for schools, including an increase in healthy food options in the cafeteria and a ban on baked goods – including cupcakes for classroom birthday celebrations – to curb overconsumption of these foods.

“Children used to walk to school, play outside and eat a home-cooked dinner. Now most children ride buses to school. Downtime is spent on the phone, playing video games or on the Internet, and dinner is often from a drive-thru or eaten quickly in front of the TV,” says registered dietitian April Schetler, who is the manager for the Virtua Center for Weight Management. “All of these factors contribute to the dramatic increase in overweight and obese children.”

Though it is not always feasible to revamp an entire lifestyle for weight loss, there are tweaks that can smooth the road, says Schetler. Having healthy foods on hand and carving time out for exercise, especially as a family, can be beneficial. One important factor is the family mealtime, she says.

“This is a great platform for parents to lead by example, preparing and serving healthy foods and enjoying the meal with their children,” says Schetler. “Creating a peaceful atmosphere for mealtime is ideal. Sitting at a table without TVs, cellphones or games promotes conversation and may open up communication about the benefits of eating right and moving more.”

Vicki incorporated some of these tactics in her home. She would take walks with Alex and prepare family meals. The benefit hasn’t just been in Alex’s appearance, but to her general health.

“Every time we went to the doctor, I’d worry they would tell me I have diabetes or a cholesterol problem,” says the Cherry Hill High School East freshman.

Heady thinking for a girl barely out of her tweens, but Alex’s fears were not unfounded. Obese children have a host of health problems, ranging from asthma to having fatty livers that look like they belong to alcoholics, that stem solely from their weight, says Feldman-Winter.

“We’re seeing high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes in the teen population. We see kids that need medication for high blood pressure,” she says. “It’s all set off by obesity.”

When parents hear what may be waiting for their child if they continue as is, it can be sobering. Feldman-Winter believes it is never too late to change the course.

“We talk about health and health statistics, and the parents are scared for their kid. The parents can feel guilty, too. Most want the best for their kids,” she says. “What’s important is they begin to change their own behaviors. It becomes a family affair when they work together to make changes.”

During the 18 months Alex has lost weight, her family has been supportive, and she and her mother have grown closer. It is one more benefit of her travels from obesity to healthy.

“We can talk on a different level now. Before, she couldn’t understand the issue. It was that you were taking her food away,” says Vicki. “No one tells her when to go to the gym. She pushes me to go. She’s more mature now.”

Alex has a simple view of it all that includes a glimpse into a mother-daughter relationship that will forever be evolving: “Well,” she says with an energetic laugh, “we don’t fight about food anymore.”