Scot Wallace, Christopher Fletcher and Brian Cunningham, Photos: David Michael Howarth

When a mother & her 6-year-old son were brutally murdered in the quiet town of Maple Shade, three law enforcement professionals spent the rest of their careers searching for the killer. Eight years later, their story has an ending.

There was a union meeting that night, so many of Maple Shade’s police officers were already nearby when the call came in. As soon as Detective Sergeant Scot Wallace walked into the apartment in the town’s Fox Meadows complex on a rainy Thursday in March 2017, he knew the scene would stay with him forever.

There was a union meeting that night, so many of Maple Shade’s police officers were already nearby when the call came in. As soon as Detective Sergeant Scot Wallace walked into the apartment in the town’s Fox Meadows complex on a rainy Thursday in March 2017, he knew the scene would stay with him forever.

“In my career, it’s probably the most horrific scene that I’ve ever had to see,” Wallace says. “I didn’t even want other officers to have to see if they didn’t have to. We all see things through our careers that are tough at times, but this one has stuck with me.”

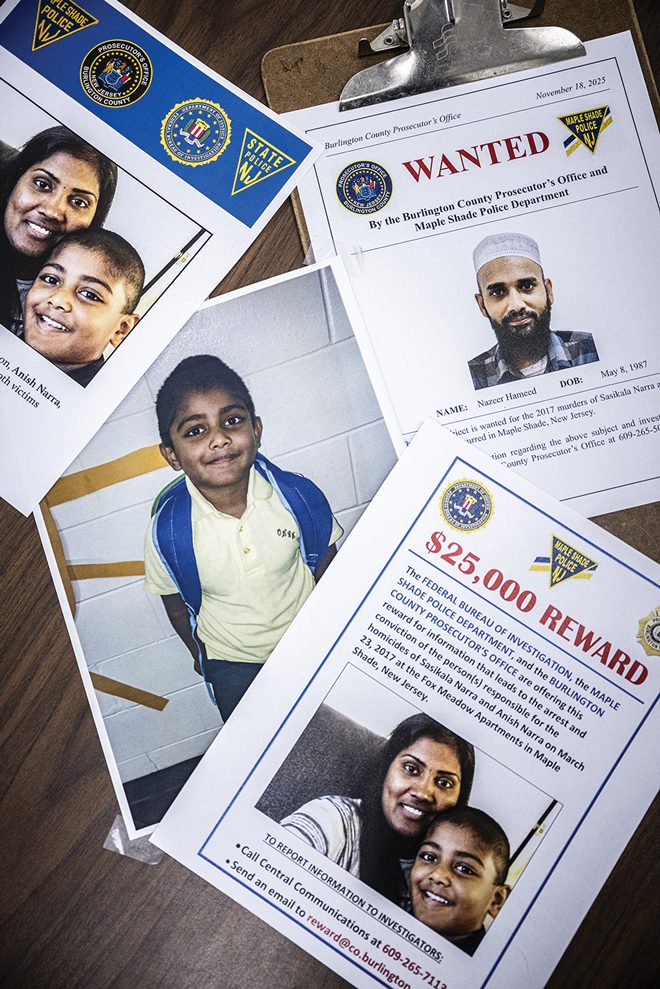

Sasikala “Sasi” Narra, 38, and her 6-year-old son Anish were dead. Blood from their multiple stab wounds had pooled on the apartment’s floor. Both had defensive injuries; they’d fought their killer as hard as they could. Hanu Narra, Sasi’s husband and Anish’s father, had found them and called 911.

Christopher Fletcher, now the town’s chief of police, was second in command in the department at the time. “We knew there was going to be incredible fear and anxiety,” he says. “You have the larger community’s concerns and fears, and within the Indian community we knew there would be a lot of fear, like is this targeted at us?”

The department responded by setting up a mobile command post – a repurposed bookmobile – “so we could just be in the middle of the community and say, ‘We’re here,’ with officers doing extra patrols while the investigators were doing what they needed to do,” Fletcher says.

The Indian community got involved, with volunteers translating the flyers police were distributing into multiple dialects.

“They kept calling it a ‘stalled investigation,’ whereas at that very moment we had people locally, federally, internationally – all the way over in India, 8,000 miles away – actively working on this case.”

“They were more than willing to do that,” says Lieutenant Brian Cunningham of the Burlington County Prosecutor’s office. “They helped us pass them out, and they encouraged anybody with information to come forward and assist the investigation, so it built into a really good community partnership.”

The case dominated headlines. The FBI got involved and at first, the investigation moved fast. But no one was arrested or charged, and time began to stretch on. Years passed. Hanu Narra moved out of New Jersey. But those who loved Sasi and Anish never forgot, and neither did the detectives determined to find their killer.

Wallace taped their photos up in his office. “I’ve looked at them every day, to remind me and to make sure that I’m not ever going to give up on the case,” he says. It remained a priority as Fletcher stepped into the department’s top spot. “When I took over as the chief, we had a meeting with the prosecutor’s office,” he says. “I made it clear this is a high priority. I want to put this case down. I always felt in my heart this was a solvable case.”

In early 2023, the second season of a true crime podcast called Strangeland premiered. Its first episode was titled, “Murder in Maple Shade.” The podcast’s producers had spent months on their own investigation, and the season of episodes raised the possibility that Hanu had killed his own family and repeatedly accused the police of giving up on the case.

“They would show up here in our lobby, and we would say the same thing ‘There’s no update we can provide you with,’” Cunningham says. “They kept calling it a ‘stalled investigation,’ whereas at that very moment we had people locally, federally, internationally – all the way over in India, 8,000 miles away – actively working on this case. They just didn’t seem to get that.”

Ultimately, Cunningham adds, “there was not a single piece of information, much less a lead, presented in that podcast that we were not already aware of. They did nothing to advance this investigation. Not even an inch.”

And while it was frustrating, both for him and for the Maple Shade officers to be “painted like we aren’t doing our jobs,” Cunningham says he was focused on doing his job. “They teach you in the police academy that you can’t be offended in uniform,” he says. “I care about my job, and I care about the victims in this case. That stuff is just noise to me.”

The truth was that the case was moving forward, and it all hinged on one piece of evidence: blood at the scene that didn’t belong to Sasi or Anish. One of them, fighting for their lives, had wounded the killer.

Not long after the murders, investigators had started to suspect a man named Nazeer Hameed. He worked with Hanu, and lived in the same apartment complex as the family. Phone and bank records showed that for a period of time leading up to the murder, Hameed had been stalking Hanu. Investigators believed the blood at the scene belonged to Hameed, and that a DNA comparison would prove it, but a few months after the murders, he’d moved back to India.

“It’s not like the movies,” says Cunningham. “You can’t just put somebody’s blood into a computer that says, ‘This is John Smith.’ You have to get a sample of their DNA to test it against what you have. If this person was on U.S. soil, then we go to a judge, apply for a warrant, and we get granted that, right? But we have no jurisdiction in India, so we have to work through the Department of Justice. As you can imagine, that is a lengthy process. Coming up with a game plan to legally obtain his DNA to confirm what we knew was the challenge, especially in a way that will hold up in court.”

Cunningham says the investigative team considered a number of different avenues for acquiring a sample of Hameed’s DNA. “His trash – that’s his own personal property. A coffee mug he drinks from – that’s technically his property,” Cunningham says. But though Hameed was in India, the company he worked for is headquartered in New Jersey, and is governed by U.S. law.

“We spoke to their security team,” Cunningham says, “and said, ‘What if we provided you with a court order for your property that happens to belong to him?’”

They were hoping he had been assigned a work cell phone or key card. Eventually, they were told that Hameed had a company laptop.

“It wasn’t easy,” Cunningham says. “It wasn’t like we asked for it and then overnight we got it. We waited months. There was an 8,000-mile chain of custody to get that laptop.”

But when it did show up, DNA samples obtained from the laptop were a perfect match to the blood found at the murder scene. “I’m actually mad at myself I didn’t think of it sooner,” Cunningham says.

In a press conference last November, investigators announced they were officially charging Nazeer Hameed with the murders. The U.S. Department of Justice and the State Department have requested that India extradite Hameed, though it’s not yet clear whether or when he might be returned to the United States to face prosecution.

“We are 110% involved in trying to get him back to the United States to face these allegations,” Cunningham says. “We’re confident that we can find him. People are prone to mistakes when they’re looking over their shoulder. If he makes a mistake, we will exploit it, and we will bring him back here.”

For Fletcher, the announcement brings a feeling of relief and satisfaction. “This is one of those cases that I really just wanted to see solved,” he says. “I’m able now to go and retire.”

Wallace says it’s been emotional to see the case reach this point. “At the time of these horrific murders, I had a 9-year-old and a 5-year-old. I had two children right in that age group,” he says. “I was emotional after our initial response to the scene, when I was trying to wrap my head around what I was just involved in and what I just observed, and I was equally emotional knowing that we’re getting some justice for these victims.”

But the job’s not finished yet, Fletcher adds. “For us,” he says, “closure is getting our defendant back into this country, having him stand trial for the crimes he’s accused of and letting the justice system take its course.”