Photos: David Michael Howarth

Steve Medio

For decades, a father and son devoted their free hours to completing the restoration of Vineland’s Palace of Depression, a unique building with a back story as bizarre as the materials in its walls. After the pair’s untimely deaths just years apart, there was question as to how the project would be finished – would it be finished.

But then a group of volunteers, led by Steve Medio, stepped in to finally finish this rare structure. The twist and turns in the story of the palace’s progress are hard to believe. And yet, it’s all true. Well, maybe not the part about the dream and the angels…and the devil.

In 1932, when the Great Depression swallowed the dreams of millions, one man found a junkyard and called it a palace.

George Daynor arrived in Vineland after buying a parcel of land sight unseen. What he found was a swampy dump. Legend has it, he climbed into the back of his truck to sleep and in a dream an angel came to him, telling him to “build a palace from the junk of the world.” When he woke, he did just that.

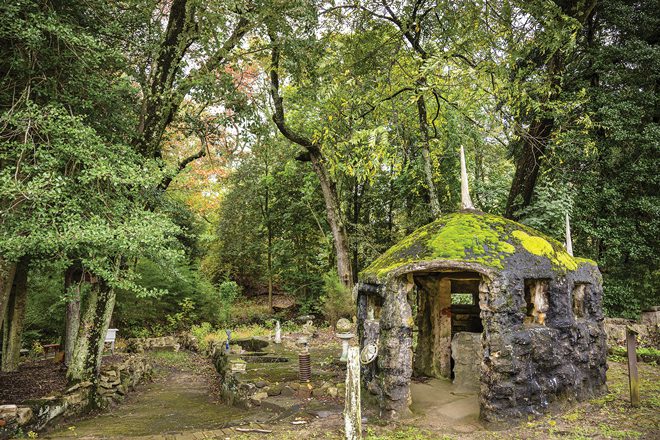

From broken bottles, twisted iron, old bricks and the refuse of others, Daynor began building the Palace of Depression – a fantastical, hand-made castle he called “the greatest piece of originality ever brought about by the mind of man.” The palace was part sculpture, part sermon and part sideshow. Daynor charged ten cents for a tour, spinning tall tales about angels, devils and the triumph of imagination over despair.

Decades after Daynor’s death, his strange creation might have vanished entirely – if not for the determination of a few Vineland residents. In the late 1990s, a city employee named Kevin Kirchner decided the Palace of Depression deserved a second life.

“He was really one of the only people who could make it happen,” says Steve Medio, current president of The Palace of Depression Restoration Association. “He worked for the city – at City Hall – and he was in charge of construction. He was a code official, and that’s exactly the kind of person whose permission you’d need to build a place like this.”

Kevin and his son, Kristian, began rebuilding the Palace from the ground up using the same spirit that guided Daynor: creativity, faith and South Jersey-found materials. The work stretched on for decades, sustained by volunteers, donations and stubborn hope. Sadly, Kevin passed away in 2020, and Kristian not long after, from leukemia.

“Kevin and Kristian left things in a very good place, far too soon, unfortunately,” Medio says. “But that part was out of our control. What mattered is that we had a clear understanding of what needed to happen, what the vision was, and how to get there.”

“When that happened, I took over,” Medio continues. “We had already developed a plan for what the team envisioned. Though, with a project like this, I’m not sure you’re ever really finished.”

Since stepping in as president, Medio has guided the volunteer team through a new era of progress.

“Over the last two years, we completed the front door entryway, the baby crib gate and the knockout room,” he says. “Nothing in the Palace is normal. People hear ‘windows’ and think it’s a quick job – but not when you’re laying glass blocks individually to form each one.”

The last time SJ Mag visited the Palace in February 2020, the team was focused on reconstructing the back wall – once covered in greenhouse plastic – using reclaimed lumber and a mix of metal and plastic roofing to let in natural light.

“Even the lumber is reclaimed,” Medio says. “All of the materials we used for the walls are recycled: brick, decorative pieces, bits of concrete and sandstone.”

The Palace now stands once again – strange, beautiful and defiantly handmade. Visitors come for tours and community events, from trolley rides to art classes.

“We recently partnered with the City of Vineland and the Historical Society,” Medio says. “The tour included rides between each site, plus walking tours of the cemetery, the palace and the Historical Society. It went really well, and we plan to keep doing it.”

Medio himself often leads tours.

“Usually, I just tell people to come on a Tuesday – that’s our main workday,” he says. “If I’m around and someone stops by, I’m happy to show them around.”

Daynor’s original palace was unlike anything America had seen – a cathedral of concrete, bottles and imagination. Visitors flocked from across the country to marvel at the junkyard creation.

“How he came up with the idea to build a castle out of junk and actually live in it – I don’t know,” Medio says. “But somehow, he did.”

Daynor was a natural storyteller and showman. He even claimed to have seen the Jersey Devil and built a “Devil’s Den” beneath the palace.

“He used to tell kids, ‘Look in there, boy – that’s the devil,’” Medio says. “It scared the kid so badly that the man who told me this story still remembered it decades later.”

But Daynor’s flair for spectacle eventually got him in trouble. In the 1950s, he fabricated a story that the kidnappers from the famous Weinberger case had stopped at his palace. The FBI investigated, and Daynor was convicted for lying.

“We actually have copies of the letters in the museum, signed by J. Edgar Hoover himself,” Medio says. “My take is that he was just trying to drum up publicity – to get people talking and visiting.”

Daynor went to prison, and the Palace’s reputation crumbled. By the time he died, the structure was collapsing. The city demolished the ruins in the 1960s.

For decades, the Palace survived only in memories and photographs – until Kirchner and his son began rebuilding it brick by brick. Their legacy now lives on through Medio and a devoted team of volunteers.

Today, the Palace is in its strongest shape in nearly a century.

“Our biggest project now is rebuilding the radio tower, the Palace’s last major structure,” Medio says.

The tower isn’t just a structural challenge – it’s a link to one of Daynor’s most eccentric passions. From that small broadcast tower, Daynor ran a radio show, transmitting from his homemade palace to anyone within range.

“He would do broadcasts from there,” Medio adds, “though I’m not sure who was listening.”

The team’s decision to rebuild the tower pays homage to that chapter of the Palace’s story – a time when Daynor not only built his own monument but tried to send his voice out into the world from it.

“The radio tower is the last major part of the building,” Medio says. “It’s separate from the main house – in George’s day, you actually reached it by walking across a catwalk from the roof.”

Once the radio tower is complete, the focus will shift to long-term care and artistry.

“It’s a roadside attraction,” Medio says. “The goal is really to keep up with preservation. Once the radio tower is finished, we’ll focus on decorative details and specialized projects – the finer touches.”

There’s still plenty of work – organizing the museum, finishing the bathroom, keeping up with repairs – but for Medio, the effort is its own reward.

“I genuinely enjoy it,” he says. “I love the place, the idea behind it, and the history of it. For anyone who’s ever visited, I always ask – have you seen another place quite like it?”