On a quiet stretch of North Church Street in Moorestown sits a park whose name most residents recognize but whose story, until recently, few truly knew.

Yancy-Adams Park, dedicated in June 1977 to two remarkable Black leaders, Roxanna Yancy and James Adams, has long been more than just green space. For decades, it was the beating heart of the town’s Black community, a place where children learned, neighbors gathered and progress was born. Now after years of neglect, the city is working to restore not just a park, but a legacy.

“Until this year, there was no sign here, nothing that explained who Roxanna Yancy and James Adams were,” says Moorestown Mayor Quinton Law.

That absence – a missing story in plain sight – became the driving force behind the movement. What began as a conversation about fixing up a small, underused park has evolved into a broader mission: to honor the Black history embedded in the landscape and to bring Yancy-Adams Park back as a gathering place for the entire community.

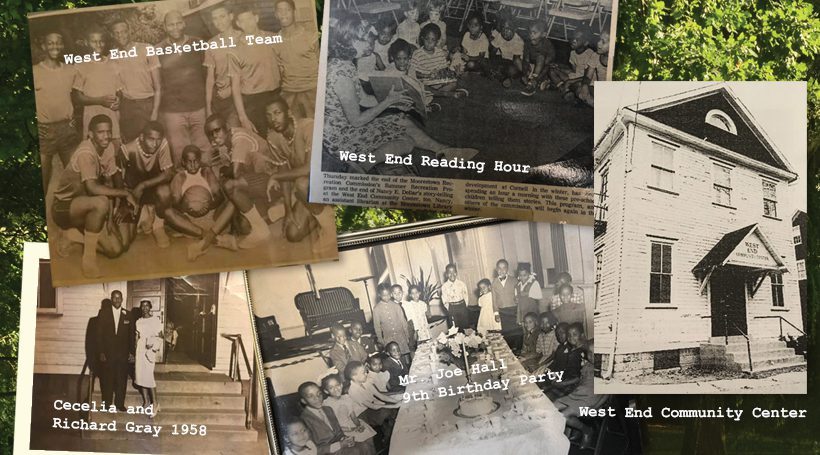

The story of this park begins with the two names that define it: Roxanna Yancy and James Adams. The West End Community Center, which once stood on the park’s grounds and served the community for 25 years, was open to everyone but especially vital to the town’s Black residents at a time when they were often excluded elsewhere. Adams served as director of the West End Community Center from 1944 until his passing in the late 1960s.

“The West End Community Center was a vital part of our Black community,” Law says. “Under Adams’ encouragement, Moorestown saw its first Black police officer, and the West End Center produced some of the town’s greatest athletes. It also empowered young Black children to pursue higher education and build their lives here in the community.”

Yancy’s contributions were equally groundbreaking. She was responsible for establishing the first kindergarten for Black children in the town. She also helped create a YWCA branch at the West End Community Center and championed peace and equality through her work with the International League for Peace and Freedom.

For a generation, the center symbolized both pride and progress. But when it closed and was eventually torn down in the late 1970s, its legacy began to fade from public memory.

“Many people even thought ‘Yancy Adams’ was just one person,” Law says. “In reality, their stories are so much more meaningful and intertwined with our community’s history.”

When Law was elected to the town council in 2021, he began hosting listening sessions to connect with residents. During one such meeting, a longtime resident stood up and challenged him: “I’ve been asking for years for the township to clean up Yancy-Adams Park. If they saw what this park looks like today, they would be very upset. You have to be the one to fix this.”

“That really struck me,” Law says. “It was the first time someone had ever told me directly, ‘You need to be the one to make this right.’”

When he visited the park, the sight was disheartening – broken lights, cracked walkways, a decaying baseball backstop and a barely visible plaque that simply read “Yancy-Adams Park, dedicated 1977.”

“It felt like such a disservice – not only to Adams and Yancy, but to the entire community,” Law says. “So much Black history happened in that space, and yet it wasn’t being honored or even recognized.”

Determined to change that, Law launched a community-wide conversation about restoring the park. Residents joined virtual listening sessions to share ideas, but the discussion soon shifted when Professor Richard Gray, a local historian, was invited to share the park’s history.

“When he spoke, it was powerful,” says Law. “At the end, several residents said, ‘Wow, if I had known the history of this park, I never would have suggested turning it into a dog park or a splash pad.’”

That moment marked a turning point.

“It showed me that when you educate your community and help them understand the history behind places, they develop a much deeper appreciation than you might ever expect,” he says.

The town began with repairs – removing the old baseball backstop, fixing the lights and walkways and installing new benches. During Black History Month last February, the city unveiled a new sign and officially rededicated the park.

“It was such a beautiful day,” Law says. “The families came out, the neighborhood came out, even the Girl Scouts were there. It was a wonderful moment of honoring the history of our community and celebrating the people who helped shape it.”

State Senator Troy Singleton helped the township secure $250,000 in the state budget for renovations. Possible plans for the coming year include a new walking path, picnic tables and a native pollinator garden.

More than just beautification, the process is about inclusion and memory.

“Most importantly, this process will be led by the community,” says Law. “We’re making sure to include the voices of those who spent time at the West End Community Center back in the day. That way, the improvements we make will both honor the park’s history and give visitors a chance to experience and appreciate that legacy for generations to come.”

Beyond repairs, the city also received a grant from the New Jersey Historical Society to launch an oral history project.

“One of the biggest challenges we faced was that there wasn’t much written history about the park or the center,” Law says. “This grant gave us the opportunity to change that – to put the word out, collect stories and preserve the memories of those who experienced the West End Center firsthand.”

Community members brought in photographs, family albums and newspaper clippings to be digitized.

“Now all of that information lives at the Moorestown Historical Society,” he says. “We have an opportunity – and a responsibility – to share these stories with new generations. It’s a matter of equity.”

“I’m for anything that can get folks coming together and working for the greater good of the community,” he adds. “Together, we’re improving this space for the next generation of families – and I think that’s truly special.”