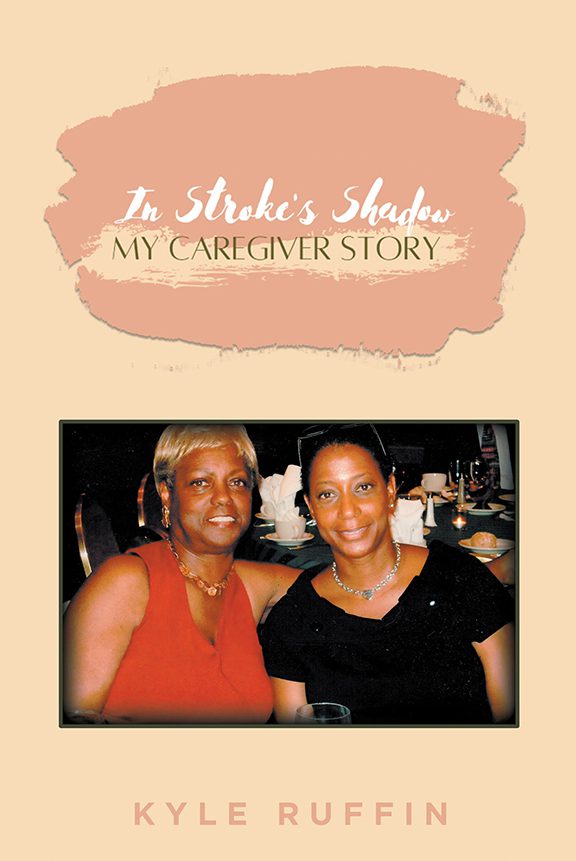

Hainesport’s Kyle Ruffin spent nearly 3 years caring for her mother after she suffered 3 strokes. In her new book, “In Stroke’s Shadow: My Caregiver Story,” she details the painful and poignant journey the two shared. She chose this book excerpt for SJ Magazine readers.

While watching a man swim in the ocean parallel to the shoreline, I saw the perfect metaphor for caregiving. The ocean is so large compared to a tiny human. The waves, before they broke, were giant swells that looked as if they were going to overtake the swimmer, drag him beneath the surface, and drown him. But instead, with each swell, the swimmer rose and fell, drifting on the ever-changing surface, never losing the rhythm of his arm stride. He stayed parallel to the shoreline as he lifted and lowered, lifted and lowered, lifted and lowered.

While watching a man swim in the ocean parallel to the shoreline, I saw the perfect metaphor for caregiving. The ocean is so large compared to a tiny human. The waves, before they broke, were giant swells that looked as if they were going to overtake the swimmer, drag him beneath the surface, and drown him. But instead, with each swell, the swimmer rose and fell, drifting on the ever-changing surface, never losing the rhythm of his arm stride. He stayed parallel to the shoreline as he lifted and lowered, lifted and lowered, lifted and lowered.

Caring for Mommy was like that. As each transition occurred or a new crisis emerged, it felt as if the giant wave of angst was going to overtake me. I expected to drown in a sea of impossible situations, pulled under by the weight of fear and complexity. But when each crisis came, the wave lifted me up to the place where solutions dwelled and lowered me back down to a calm place, into a short-lived routine, which was often, and without advance notice, disrupted again and again.

Acute rehab was the first of Mommy’s four-phase recovery process. The rooms of the rehab facility were painted in light pastels and cream colors. Each accommodated two patients with beds that had long institutional fluorescent lights hanging above the headboard. Each patient had a unit that combined drawers, a mirror and counter, and a small closet. The space was clean and tidy but extremely tight for something a person was expected to live in for the next month.

I immediately began decorating her room with all her cards, stuffed animals and flowers, like a mother decorating her daughter’s new dorm room. I tried to fill it with things that reminded her of her life just two short weeks before. Books I found at the side of her bed, clothes from her closet, pictures of her traveling.

Moving to acute rehab meant the real hard work was about to begin. In the hospital, a therapist only spent about ten to fifteen minutes with her. In acute rehab, she’d have to endure up to four hours of therapy six days a week.

Mommy wasn’t the kind of person who regularly worked out. She’d taken up walking with her girlfriends, but that was more social than exercise. Thanks to her genetics, half of which was completely unknown, she was in good shape for a 68-year-old. She fancied herself a dainty lady who barely bent her knees and pointed her toes when on the rare occasion she needed to run. She ran like a movie star with cameras rolling, driven by a need to appear glamorous.

Mommy didn’t understand the mechanics of repetition and muscle memory. She wasn’t familiar with biophysics or how the brain learns. It wasn’t easy educating her about these things either because, in her mind, she knew everything. Mommy was like a teenager who refuses to believe their parents’ dictates are based on proven knowledge instead of the desire to deny their child what they want.

When the speech therapist asked her to say something simple, like saying “My name is Paula” out loud, she’d roll her eyes and give a look that said, “This is ridiculous.” I know how to say my name. But in truth, she was no longer capable of saying a mindlessly easy phrase that she had repeated over and over once she mastered it as a child. Eventually, she’d give in, try, and was surprised each time by how difficult it was to say whatever she wanted on demand.

When occupational and physical therapists explained why they had her do certain things, it made total sense to me. I was a star athlete in high school and a lifelong gym rat. I knew the benefits of repetition and how to build strength because I had lived it. In late-night, marijuana-fueled debates in college, I had learned from one of my closest friends, Flavia, the PhD candidate in psychology, about how the brain develops grooves that store the memories of repeated motion and experience. That’s how we do things without having to think about them.

The practices I read about in my Psych 101 textbooks at University of Delaware and altered state theoretical debates now meant something. In college, I wondered, “Will I ever need this information?” I imagined I’d need to tap into what I’d learned sometime during my career, not in my personal life. But here I was, trying to explain to my 68-year-old mother how the brain, her brain, worked. She wasn’t buying it.

Mommy never went to college. She dropped out of high school in her senior year to have my sister, yet she still believed herself to be wise, worldly and well-educated. She knew everything she needed to know about successfully navigating life. After all, she watched Dr. Oz and The Doctors every day. Beside her bed, she kept books about herbal remedies and preventative health that would tell her what she needed to know, but I couldn’t tell if she ever bothered to read them. To her, that was enough for her to hold her own against anyone with a medical degree.

I tried to explain why it was important that she do things she considered childish. That she needed to relearn what she took for granted two short weeks ago. Why walking, writing, and talking – things she previously did without effort – would require the intensity of an athlete in training.

“Mommy,” I said, “this is going to be the hardest thing you’ve ever done in your entire life.” I tried to give her mental tools she could use to work past the point where she’d normally give up. “All I ask is when you get to the point where you don’t think you can do it anymore, please try one more time.”

Every day, I had to convince her to fight harder than I’d seen her fight for anything. And when there were setbacks, I had to remind myself regularly to pull back on my reflex to respond with criticism or anger. I took great pains to encourage her and support her recovery with my words and body language. This was a very different dynamic for our relationship, but one the therapists convinced me was important if I wanted her to get better. Since I was still operating on the premise that she’d make a 100% recovery, I followed their advice.

It seemed to work, but there’s a thin line between motivation and nagging.