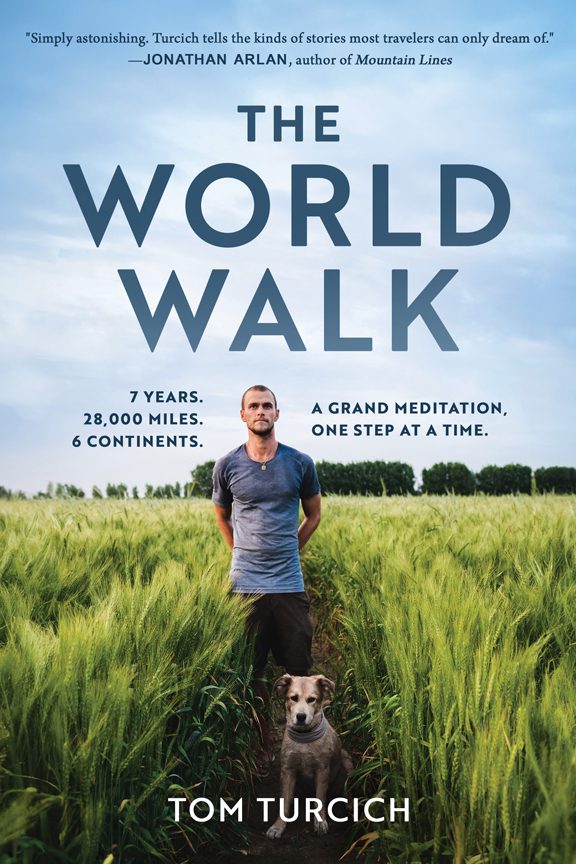

In 2015, Tom Turcich left his Haddon Twp. home to begin a walk around the world that took him through 6 continents over 7 years. Accompanied by his trusted companion – his dog Savannah – Turcich saw beautiful places, made friends and tried food many of us have never heard of. His mesmerizing stories are endless, and some are now published in his memoir, “The World Walk,” available this month. He chose this excerpt about his family visiting him in Croatia for SJ Mag readers.

********

One afternoon, Smiljana told us there was a cemetery where most of the Turcich relatives were buried so we made our way to it by following a back road on the west side of the island. It took us a long time to find the place, but eventually, at the end of a dirt lane, we came to a stone church with a bell tower high above the trees.

Behind the church were a hundred burial plots bordered by an iron fence. The plots were familial and the headstones were marked by black-and-white portraits. There was Maračić, Žgombić, Bogović, and on about a third of the headstones was Turčić.

“Crazy,” my dad said in a low voice.

My parents and Lexi made a slow lap around the cemetery then went to the steps out front to rest in the shade. I lingered a little longer, crouching before a headstone with a hand on the raised bed where weeds burst through the soil. I couldn’t take my eyes off the name.

In Ireland, I wasn’t capable of fully appreciating my connection to the place. Although I visited my great-grandfather Andrew’s home and stayed with relatives across the island, the place was too alive for me to feel my ancestral roots. But now, gazing upon the name Turčić carved in stone, it was as though everything I’d been told about my family was verified. My ancestors were real. I had come from this island.

The next day, we met cousins at a restaurant in Dobrinj—a hilltop village with views of the Adriatic. Smiljana, Edi, and the girls were there, as were Uncle Ivica, Aunt Katica, and cousins Ivana, Lucija, Igor, Mia, and Dora. We occupied two tables aside the piazza. Zora was one of the few restaurants that made traditional šurlice, a Krk pasta tediously crafted by coiling each piece of dough around a wooden stick then dousing the finished pasta in a beef goulash.

“What do you think of your motherland?” Smiljana asked my dad.

“It explains why we were raised on a river and why my dad was in the Coast Guard.”

From lunch we drove to Gostinjac, the village beside Dobrinj, where my great-aunt Dusica and her husband lived. Dusica had a garden that wrapped around her house, and in the back, she had a small farm with corn and chickens.

“She’s the toughest woman you’ll meet,” Smiljana told me as we approached. “She runs the whole place by herself. She used to have goats, chickens, potatoes, and just about everything else, but Nikola fell sick and taking care of him has taken up most of her time. Nikola was strong in his day, but he’s almost ninety.”

The cousins descended on Dusica’s home like a swarm. In her basement, Dusica pointed to the bottles of homemade rakija and the hocks of prosciutto she’d hung to cure. I took a swig from one of the wicker-covered bottles and thought I ingested gasoline. Lexi was in tears with laughter.

“Why would she keep gasoline in there?” she said.

“I don’t know, but that can’t be drinkable.”

After showing us her home, Dusica led us across the street and down a narrow stone-walled lane. At a bend, we came to the gate entrance of two stone houses.

“Your great-grandfather Anthony’s home,” said Smiljana. “The one further away. The family used to own the land, but it’s not ours anymore. Someone remodeled it recently.”

“It’s in good shape.”

“Dusica says it’s a young doctor and his family.”

We took the lane a little further and it tightened between the walls until we stopped at another stone house that was only three walls and a caved-in roof. A mound of stones was set beside the house as though the missing wall had been dismantled piece by piece.

“This was your great-great-grandfather’s home.”

I couldn’t see much of it because the bushes were so overgrown.

“Gives you an appreciation for your ancestors, doesn’t it?” said my dad. “How anyone managed to live here, I don’t know.”

“It’s no wonder they came to America.”

“And on the back of a pamphlet. We wouldn’t be here if they hadn’t.”

At that moment, I wondered if my need for adventure came from my dad, or if it had been in our blood for generations. Maybe Anthony and his brothers didn’t leave Krk because it was a barren island of stone and a pamphlet promised more in America; maybe they left simply for the adventure of leaving. Maybe we had both left in order to satisfy that innate need to reach into the unknown. Whatever the motivation, Anthony was successful. He made it to America. He built a life in Philadelphia and his progeny multiplied into the hundreds.

After a week on Krk, my parents and Lexi returned Savannah and me to Zadar. On our final afternoon together, we hired a boat to take us onto the water to watch the sunset. Alfred Hitchcock called Zadar’s sunset the best in the world. When we came to a stop, I jumped off the side and swam out. When I was far enough away, I looked back to the boat. My dad was talking to the captain, Savannah was watching me from the stern, my mom and sister were chatting on the bow. The sunset was nearly green in the haze. I thought of my great-grandfather, Anthony—how by leaving Croatia he brought us back to it.

Copyright ©2024 Tom Turcich. Excerpted by permission of Skyhorse Publishing Inc. All Rights Reserved.