When Mary Previte was 9 years old, armed men appeared at her boarding school in China. She spent the years of World War II in a Japanese concentration camp, starving, freezing and struggling to maintain some semblance of a childhood. The Haddonfield resident, now in her 80s, is eager to share the story of what she endured and her recent search for the seven men who set her free.

Your father was British and your mother American. Why was your family living in China?

My parents were both third-generation missionaries to China. They met at college in the United States and moved back to China to continue their missionary work. I was born in China in 1932.

By the time I was school-aged, the war was really heating up. My father rescued more than 1,000 women and children by bringing them into the missionary compound in Henan Province. I remember there was a huge American flag painted atop the church to show the bombers we were there.

It was a war, yes, but it wasn’t our war, so life just went on. My siblings and I needed an education, and the only place to get an English education was Chefoo School, a boarding school that all the missionaries’ children attended. My siblings and I were there in 1941.

Can you talk about the experience of being thrown into a concentration camp at 9 years old?

The day after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese appeared at the gates of Chefoo School with a Shinto priest. They performed ceremonies all over the property, saying it all belonged to the “Great Emperor of Japan.”

For the first year, we stayed at school. After that year, they wanted to use the school property for some other purpose, so they forced us out. They loaded us on a boat, then a train, then crammed us into trucks like animals. This is how we arrived at Weihsien.

We came into a camp that was already full of people. There were businesspeople, entertainers, doctors, Protestant and Roman Catholic priests and nuns. There were a lot of British people, but also some Americans, Belgians, Scandinavians, Canadians, Australians – the Japanese had rounded up every person they could find from Europe or North America. We were considered enemy aliens.

What were the conditions like inside the camp?

I lived a miracle in the Weihsien Concentration Camp. We were part of a war and I was only a child, but I honestly only remember one time being afraid. My teachers made sure we got to remain children. They started a Brownie troop, and we learned everything Brownies learn. I can still set a sprained ankle and tie all kinds of knots. The teachers said, “School will go on. We will win this war, and when we do, you will compete with boys and girls who have been going to school all this time, and so school will go on.”

Every challenge – and I’m using that word politely – was turned into a game. Saturday was the Battle of the Bedbugs. We’d hold rat-catching competitions. My little brother John was the winner of the fly-killing championship.

We were always hungry, but we never lost our humanity or even our manners. You could be eating boiled animal brains out of a soap dish, and a teacher would come up behind you and say, “Mary Taylor, sit up straight!” They were right. People who gave up those normal routines got sick.

The grown-ups did everything they could to create a normal world. There were concerts, classes and lectures. They’d put on plays. They did “Androcles and the Lion,” by George Bernard Shaw, and the armor was made from hammered-out tin cans. There was even a band that was imprisoned in Weihsien, the Salvation Army Band. They’d practice this anthem – it was a mix of the Canadian, British and American national anthems. They’d say, “We will win this war, and when we do we will need a victory medley.”

Is it more frightening when you look back on it as an adult?

There was barbed wire and booby traps and guard towers. We wore our prisoner numbers at all times. We children used to watch the Japanese doing bayonet drills. I don’t think we realized at the time that they were practicing killing.

I don’t remember too much interaction with the Japanese guards. They were there, in the towers, and they patrolled the grounds with dogs. We had role call every day, and we children learned to count in Japanese, so we would count ourselves off. When they brought Japanese dignitaries to the camp, they’d always come to hear the “little foreign devils” count in Japanese. You must remember; this is a child’s story. But I found one of the teachers later – Miss Carr – and I said, “Now I’m grown up, and you can tell me. What were you feeling?” She said, “Mary, I prayed that when they lined us up at the edge of the death pit, they’d shoot me first so I wouldn’t have to watch.”

Do you remember the day the Weihsien Camp was liberated?

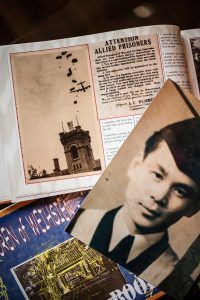

I remember I was sick with an upset stomach. It was the heat – it was so unbearably hot you couldn’t even walk barefoot on the dirt. I was lying on the steamer trunk I used as a bed, and I thought I heard an airplane. It got really loud, and I ran to the window and looked out. And there it was – the American star on the bottom of the plane’s wings. That was the first time I ever saw a parachute. I started running for the gates, thinking I’d be the first one there. Well, when I got to the gates there were already 1,500 people there, screaming, crying and dancing. It was hysteria. People went berserk with joy.

There were rumors the war was ending, but we certainly didn’t know it. And these Americans had no way of being certain that our Japanese guards knew the war was over. But they must have gotten the news, because they didn’t fight the liberators. The men in our camp pushed through the gates, picked up the Americans and carried them in. The band on the hill began playing the victory medley. When they got to, “Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave…” the American trombone player just crumpled to his knees, weeping.

What made you decide, decades later, to go looking for the liberators?

What made you decide, decades later, to go looking for the liberators?

I’d read so many things through the years about the Nazi death camps in Europe. The same happened in Asia, in both military camps and civilian camps like mine. I just kept thinking, “I lived a miracle.”

In 1997, I decided I would find the six Americans who came to our camp. We all had their autographs, and below their names they’d written where they lived at the time. I thought that might be a good starting point. A friend did a national search for me and gave me a huge folder full of addresses and phone numbers for people with the same names as the liberators. I sent letters with self-addressed envelopes, asking, “Are you the man who liberated the Weihsien Camp on August 17, 1945?” I got letters back that said, “God bless you, Mary. I hope you find them.”

How long did it take you to find all the men?

Not long after I started talking about it, I got a call from a woman who lived in Moorestown. She said, “Mary, Raymond Hanchulak lives next door to my sister in the Poconos.” Raymond was the medic on the team. I called and spoke to his wife. She said, “Raymond died last year.”

After that, I became very afraid that I was going to miss my heroes. The next one I found was Peter Orlich’s widow, Carol. She said, “Oh, oh, my Pete died four years ago.” I said to myself, “Mary, you have got to hurry. They will all be gone, and you’ll miss your chance to say thank you.”

Soon I got a phone number for Tadashi Nagaki. He was a Japanese-American who was the unit’s translator. After the war, he moved back to Alliance, Neb. and became a farmer. Well, I called and asked for Mr. Nagaki. He said, “Speaking,” and I just started to cry. He helped me find Jimmy Moore in Dallas, Texas – they’d stayed in touch. After the war, Jimmy worked for the CIA until he retired. He said he’d help me find the rest of the men, and I thought, “Well, now I have a spy on my side!” Not long after that, he called and said he’d found Major Stanley Staiger in Reno, Nev.

So now the list of Americans only had one more name. By the end of the year, Jimmy called and said, “I found James Hannon in Yucca Valley, Calif.” I was deliriously happy.

Once you’d spoken to all the American men – or their widows – did you feel like your quest was completed?

I realized I needed to thank them all face-to-face. That took me two years of crisscrossing the country. I can tell you that America’s heroes come from every walk of life, and every corner of the land.

Two days before Jimmy Moore died, he called me and said, “Mary, you’ve made my retirement so very interesting.” I am just so grateful to have found them and to count them as my friends.

There was one more member of the team that liberated the camp. You thought you’d never find him, but he kind of found you, correct?

Thank you, thank you, thank you lord for the Internet. I had tried, with no success, to find “Eddie” Cheng-Han Wang. He was the youngest member of the team, the Chinese interpreter. I’d given up on ever finding him. Early this year, I wrote an article for the Weihsien website about finding my heroes, and at the end I mentioned I was still looking for Eddie Wang. In March, I got an email from a young man named Daniel Wang, who was living with his wife on a visitor’s visa in South Carolina. He said his grandfather, who lives in rural China, was the Eddie Wang I was looking for.

Now that you’ve officially found all the liberators, what’s next?

I’ll continue to tell the story of Weihsien at schools and senior centers, and anywhere else I’m invited to tell it. I will continue to tell people the names of my heroes – my angels – including Eddie Wang. What a miracle to have found this man. I’m sure I will visit Mr. Wang to say thank you to the last remaining hero of Weihsien. It’s the right ending to this story.