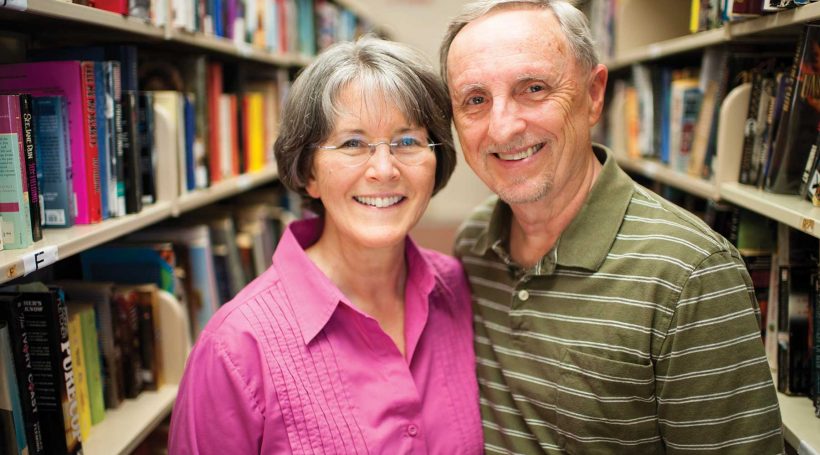

Ruby Rodriguez hasn’t been at home in Camden with her three children since 2003. She’s serving a 17-year sentence at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women in Clinton for aggravated manslaughter.

Unlike many of the women incarcerated at Edna Mahan, Rodriguez, 36, sees her children fairly often. But to fill the gaps between visits, she participates in Project Storybook, a program that has inmates record themselves reading a book. The books and CDs are sent to the inmates’ children, who get to hear a bedtime story from Mommy – even though Mommy’s not home.

Ruby Rodriguez

“When I got here, my kids were young, and I was coming away for a long time,” Rodriguez says. “When you have something like this, this little attachment that helps you bond, it counts for something. My kids have been coming to visit regularly since I’ve been incarcerated, and I’m very lucky to have that – a lot of the girls here don’t ever see their kids – but this is something they can listen to between visits.”

Rodriguez’s kids are teenagers now – Irvin is 17, Jacob is 15 and Victoria is 13 – but she still participates in programs like Project Storybook, because she says it’s helped her build an open and honest relationship with them.

“When they were little, I don’t think they knew why I was here,” she says. “Once they got old enough, I told them, ‘You can ask me,’ and they did. I’m honest, for the most part, and their reaction is always, ‘It don’t matter, we love you, you’re our mom.’”

That honesty is important, Rodriguez says, for making sure her children stay on a safe path to a successful future.

“I tell my kids the truth about who I was and my lifestyle,” she says. “I did things I’m not proud of. I sold drugs. I broke laws. I tell them, ‘All actions have consequences, and I want better for you.’ My mom was incarcerated here, and I followed in her footsteps, but that stops with me. Whenever I see them derailing – grades slipping, priorities out of line – I say, ‘Hey, you wanna come here?’ I wasn’t raised in the street. I never wanted for anything. Me being here is not my parents’ fault. It really can happen to anybody.”

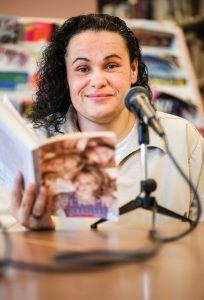

No one, perhaps, knows the truth of that better than Mary Pappas, a 46-year-old Atlantic County woman who is more than halfway through the five-year sentence she received after she ran a stop sign a few miles from her home and struck another car, killing its driver. Pappas’ blood alcohol level was 0.15, and she pled guilty to vehicular homicide.

Inmate Mary Pappas records her story with volunteer Emil Brisson

Pappas has been participating in Project Storybook since she arrived at Edna Mahan, sending books and CDs home to her daughters Laycie, 8, and Ava Rae, 7.

“First of all, they just love getting packages. It’s really exciting for them,” Pappas says. “We’ve always been a reading family. There are a million books at home, and they’re all like little escapes for the girls. I love sending them a new book, and with the CD they can hear my voice whenever they want.”

The most recent book Pappas sent home was “Freckleface Strawberry,” a children’s book by actress Julianne Moore. Before she began to read, Pappas leaned into the CD recorder on the table to say, “Hi Laycie and Ava! I chose this book because I know you’ll both giggle at all the funny parts. See you soon.”

Once she’s finished recording, Pappas addresses envelopes and fills out shipping labels provided by Pat Brisson, the program’s volunteer coordinator. Brisson, 64, a teacher and children’s book author, started the program at Edna Mahan in 2003 after the publication of her book “Mama Loves Me From Away.”

“The book was inspired by women like these inmates, who are being mothers to their children despite being in prison,” Brisson says. “After I wrote it, I thought, ‘Well, the only state prison for women is

20 minutes from my house. I should see about going there to volunteer.’ So I did, and they were trying to figure out what would be suitable for me to do. I’d heard about similar programs at other prisons, and when I brought it up it turned out they had gotten a grant to do this program – they had tape recorders and books – but they had no one to run it. I’ve been doing it ever since.”

A few weeks before each scheduled recording session, Brisson provides inmates with a selection of books ranging from picture books to novels. Women are invited to participate regardless of their children’s ages.

At the recording sessions, held every other month, Brisson, her husband Emil and a team of volunteers man the three CD recorders. On average, Brisson says, 25 women will record books for their children in a single evening.

“I’ve been told it’s one of the few programs at the facility that consistently gets pretty good numbers of people signing up for it,” she says. “That’s been gratifying.

I also think the program is so important for the moms and the kids. I’m a mom and a writer, and books and reading are dear to my heart. A bedtime story or a story during the day is such an important part of a kid’s life. That’s why the tape is so important – your child needs to hear your voice, and reading a book to them is going to inspire your child to listen to it over and over, and that’ll help with their own literacy.

“Even if your children are older,” Brisson continues, “you can choose a novel and read it ahead of time. You can record yourself reading the first few pages and say, ‘I can’t wait for you to read this so we can talk about it together.’ It’s an opportunity that these moms and kids might not otherwise get. I had one woman say, ‘You know, my daughter was always asking me to read to her, and I never had time. Now I have nothing but time.’”

Brisson says her volunteers are often surprised when their preconceptions about prison – and the inmates – turn out to be significantly off the mark.

“So many of my volunteers have said, ‘It’s so moving to do this and to watch this,’” Brisson says.

“You’re there with a woman who is expressing her love, talking and singing to her kids. It’s the moment when she’s most vulnerable. I’ve had people in my life say things like, ‘Well, they made their choices, why do they deserve this kind of help from you?’ And I think, ‘OK, but their children didn’t do anything wrong, and making mistakes doesn’t mean they aren’t still mothers.’ You see some of these women with tattoos on their necks and down their arms, and in another situation you might think, ‘Oh, I should be afraid of her,’ but we don’t see that anymore. We just see moms.”

In 2004, Brisson was awarded the N.J. Governor’s Volunteer Award in Human Services for her work with Project Storybook, and in 2014 she and Emil were the N.J. Department of Corrections Volunteers of the Year, but she’s not after praise or thanks. What she really wants, she says, are a few microphones.

“I don’t need more thank-yous,” she laughs. “I need microphones! The whirring of the CD is pretty loud in the background of the recordings. It would be so much better if we had microphones.”

Project Storybook is just one of numerous programs Ruby Rodriguez has taken advantage of during her incarceration. At the beginning of next year, she’ll be released to a halfway house to serve out the last months of her sentence, and she plans to be ready.

“Ten more months and this nightmare is over,” she says. “I’ll be in a halfway house within a block of my kids, and in 2018 my parole ends and I’m done with the system forever. I got my GED here. I graduated in July and started taking college courses. I’ve truly benefitted from this experience. I’ve learned to remind myself what’s really important. I’ve found myself in situations where my temper wants to get the best of me – that’s my one big demon – but then I think, ‘Ten days in lockup or a visit from my kids?’ The visit trumps the demon every time.

“Fourteen years in a place like this strips your humanity, but I’ve spent this time bettering myself for my kids. My oldest is really into boxing. My 15-year-old wants to join the Army, and Victoria is a real bookworm. I’m going to watch them become adults and become successful people. I am never coming back here.”

When Pappas was sentenced, her daughters were barely old enough for kindergarten. When she gets home in January of 2017, they’ll be closer to middle school.

“They’ll be different,” she says. “They’ll probably understand more about why I was gone for so long. At first, I lied to them. Now they know there was an accident, but I don’t think they know or understand that someone died. But when I get home, they’ll be older. It will be different.”

For now, the best Pappas can do is keep in constant contact, sending books through Project Storybook, writing letters, completing the half-finished coloring book pages the girls send and counting the days until she gets to go home to them.

“I talk to them every week, and they seem happy,” she says. “They’re doing well in school – they’re so smart. I have a big family, and they have my mom and sister, and my husband’s family too. Most importantly, they have each other. It could be so much worse. They could be in a foster home or maybe even split up. Instead, they’re safe at home with their family, their dogs and chickens. That’s what I have to think about.

“I have to keep a positive attitude,” she adds. “It’s easy to get sucked in here, to get depressed or to get down on yourself. I don’t allow that. I was a good mom. I am a good mom.”