It’s a hard-to-believe story, and yet it’s true. A young man from Burlington County loses his arm in a freak accident and still fulfills his dream of becoming a surgeon. Some people just don’t give up.

Growing up, Dorothy Talavera knew better than to complain that life wasn’t fair to her father.

“One of the most valuable lessons he taught us was not to be defined by your circumstances,” says Talavera, who lives in Delanco. “There were no excuses. He believed life was what it is. Now deal with it.”

Morris Robbins took his advice to heart. In 1935, when he was just 18, his own circumstances took a dramatic turn, throwing a wrench into his plans of becoming a surgeon. As a result of a freak electrocution accident, Robbins lost his left hand and had third degree burns over 80 percent of his body. But as he saw it, this was not a reason to end his dream.

“ Things that normal people could do and that he’d been able to do all his life, he couldn’t do anymore.”

“We can’t imagine the excruciating pain he experienced. He never talked about the pain,” says Talavera, who recently published her father’s story as a book, “The Life and Times of a One-Armed Surgeon.”

“He was burned over most of his body and he was not expected to live. People were horrified at his appearance. Things that normal people could do and that he’d been able to do all his life,” she says, “he realized he couldn’t do anymore.”

Robbins, who died in 2004 at 88, did become an orthopedic surgeon, and a well-respected one. But his path was full of obstacles, most of which he overcame, Talavera says. Among the most stinging were the many rejections he received from medical schools, many of them bluntly citing his physical limitations as reason he could never practice medicine. Even after he eventually became a surgeon, Robbins was snubbed by some medical groups whose approval he so coveted.

“His patients, to the best of my knowledge, never gave him a hard time about his disabilities,” Talavera says. “But he experienced a lot of disappointment in his lifetime. Although he did well on the boards and was a certified surgeon, he was never accepted by the elite medical societies. They never allowed him to join.”

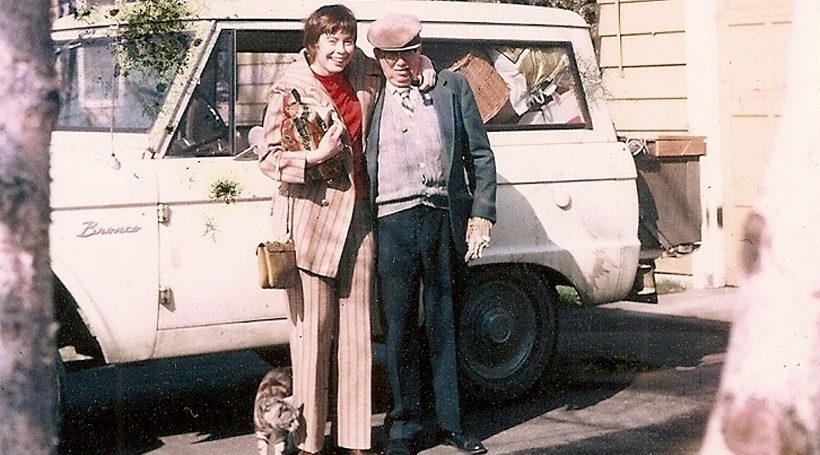

Dorothy Talavera and the artificial hand her father built / Photo: David Michael Howarth

Robbins’ life changed the night of August 20, 1935. He was driving his girlfriend home on what was meant to be their last date before starting college, when the pair came upon a car crash on a stretch of a rural Burlington County road. The vehicle had struck an electric pole.

Although he couldn’t know this when he approached the wreckage to check on survivors, wires carrying 33,000 volts had landed near the damaged car. After stepping on a fallen wire hidden by tall, wet grass, some 33,000 volts shot through one of his arms and out the other.

Robbins woke up in a hospital bed with burns covering 80 percent of his body and no recollection of what happened to him. His left arm was beyond repair, forcing amputation below the elbow. His right hand lost some mobility as well.

Robbins underwent 15 surgeries over the next 2 years. It was a time before prosthetic limbs were widely available so he set to work designing his own prosthetic. He experimented with strings to manipulate fingers and rubber bands to function as tendons. Talavera recalls her father perfecting the use of a fishing line, which was wrapped behind his right shoulder, to control the movement of his wooden left hand.

As bad as things were, he never lost faith.

“I was convinced that God had saved me for a purpose, and I was determined to live through this experience, recover and act according to His will,” he wrote.

Three years later, he finally was able to pick up where he left off, starting his pre-med studies at the University of Pennsylvania. The natural next step was medical school. However, despite stellar grades, Penn and nearly every other medical school rejected his application.

One outlying possibility was the University of Virginia, which didn’t reject him outright. They put him on a waiting list. So Robbins decided to take matters into his own hands. He persuaded a friend to drive him to Virginia so he could argue his case for acceptance in person. But fate intervened when traffic ground to a halt in Baltimore directly in front of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. He decided to try his pitch there instead.

With a half-hatched plan to present his case before the dean, he found an elevator labeled “To the Dean’s office. Not for student use” and threw caution to the wind. The door was locked but he asked for help from a man who happened to come along, Talavera says.

The 2 struck up a conversation on the elevator. Robbins mentioned he was looking for the dean’s office, and the man escorted him there. At that point, Robbins watched in disbelief as the man walked around and sat behind the desk. The rest of the interview was brief. “We need you in medicine,” the dean said by way of welcoming him into the medical school. Robbins went on to take all the most difficult lab courses, determined to show he could do the work, Talavera adds.

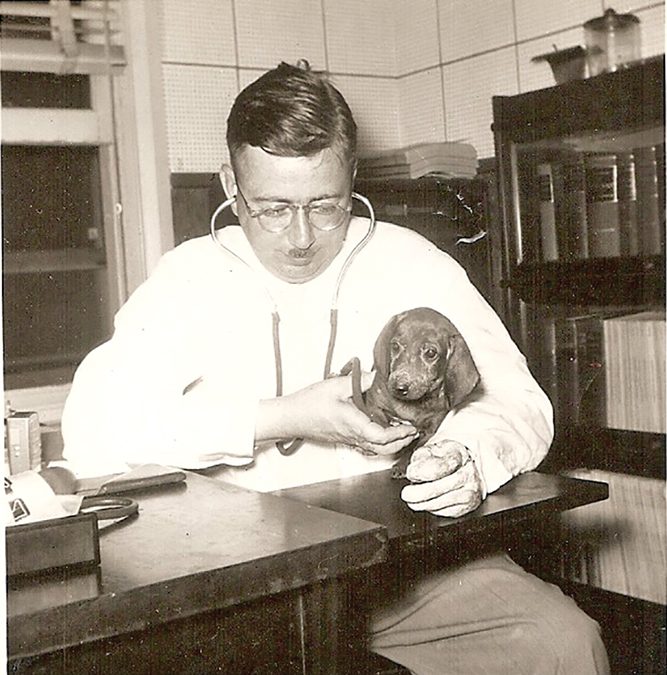

For the first 10 years of his career, he worked as a general doctor, but he still yearned to be a surgeon. At the time, with so many soldiers coming home without limbs after World War II, orthopedics was emerging as a new field, Talavera says. Fascinated, he decided to be an orthopedic surgeon.

“I used to tease him that his father was a carpenter, and being a surgeon was like being a carpenter except with bones,” she adds.

After landing an orthopedic residency at the Hospital for Crippled Children in Newark, Robbins was admitted to Penn’s emerging orthopedic surgery program, where he earned top grades and went on to board certification.

As a kid, Talavera spent a lot of time hanging out at her father’s office watching the man known simply as “Doc” treat patients. To her, his prosthesis was nothing out of the ordinary. But she smiles recalling how he won over skeptical young patients.

“He would sit on a low stool, so he was down at their level,” says Talavera, now 72. “He’d offer his arm and say, ‘Go ahead, do with it what you want.’ They would pinch it, and they would hit it, and they would tickle it, saying, ‘Can you feel that?’”

“Then he would show them how the fingers opened and closed. Finally, when they were satisfied with that, he would very gently take their wrist in his prosthetic hand so they could see it didn’t hurt, and with that, he had them. They felt comfortable, they felt relaxed, and he was able to treat them.”

In rural Burlington County, where farming accidents were common, Robbins was known as the surgeon who could often save the limbs of patients whose doctors advised amputation, Talavera says.

“He wanted to spare people the indignities and hostility that the world has for the disabled and those who’ve lost a limb,” says Talavera.

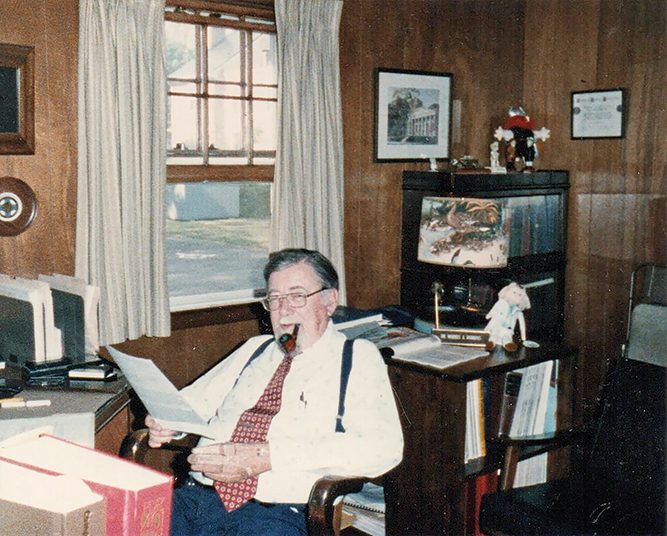

Robbins knew people would have a hard time believing everything he went through to pursue his dream. That’s what motivated him to write the memoir, Talavera says. He never intended for it to be published, and instead gave out chapters to family members each Christmas as he wrote them.

It was only after his passing in 2004 that Talavera decided to revisit the manuscript. After discovering a filing cabinet full of her father’s letters, newspaper clippings, photos and other documents in her childhood home, she made it her mission to publish his words, supplemented with the new information she dug up.

The book has revived interest in his story, Talavera adds, noting how revered her father was in their town. To this day, Talavera runs into people who regale her with stories of her father, including the man who delivered mulch to the house last fall.

“He said, ‘I’ve been meaning to tell you – your father saved my father’s life.’” Talavera says. “His dad had a fall at work. He broke his back. My dad showed up and performed surgery, and not only saved his life, but the man was able to walk again.”

Besides the book, there are other reminders of his impact. After his death in 2004, the small access road leading to the riverfront near the Delanco house was renamed Robbins Lane. Talavera considers that validation of his impact.

“In the end, he got the last laugh,” Talavera adds. “None of those elite guys have a street named after them. It’s final proof of his work and the legacy he left behind.”