Carly Altenberg, 19, always wondered why her grandmother, Lilo, had the numbers A81758 tattooed on her arm. When Lilo passed away in 2011 at the age of 90, Carly regretted never having the courage to ask her.

But while cleaning out Lilo’s Cherry Hill home, the family discovered a trove of letters her grandmother had written, some in English, others in her native German. They were addressed “to my grandchildren, their grandchildren and the grandchildren after that, and so on and so on.” Once translated, they learned of the horrors she faced living through the Holocaust.

Hans and Lilo Altenberg moved to Cherry Hill in 1991; the young couple posed for this engagement photo in Berlin

The letters told of a happy time when Lilo Sommerfeld, 15, and Hans Altenberg, 19, met in Berlin, Germany, and became engaged. “They were going to get married in 1940, but the war got in the way,” says Carly, a sophomore at Juniata College. Her grandfather took a relative’s advice and got a job as a steward on the S.S. Groenlo, a ship traveling to America.

“He begged my grandmother to go with him, but she wanted to stay with her family,” Carly says. Once in America, Hans left the ship to avoid going back to Germany. Without the proper paperwork to stay in America, Hans found his way to the Dominican Republic, living with other Jewish refugees.

“My grandmother had a different story,” says Carly. Her parents traveled to Holland and shortly after, Lilo went to join them. She hid her family’s jewelry in a sanitary napkin covered in ketchup.

“When she got there, her mom didn’t know whether to hug her or slap her,” adds Carly. “She would have been shot on the spot if caught.”

That was the first of many scrapes with death for the feisty young woman. The Nazis came into Holland, and the bombing forced the family into a bomb shelter 10 to 15 times a day. Lilo worked in a sewing factory and was twice picked up and detained by police on her way to work – for being Jewish.

“Her dad was able to supply paperwork and get her released,” Carly says.

“Then, one night at four in the morning, there was banging on the door. It was the Nazis, and the family was told to pack one bag per person. They had to march to the Schouwburg Theatre in Amsterdam, where they spent 10 days before being sent to a concentration camp. They were loaded like animals – my grandmother’s words – onto a cattle car, where she and her mother were immediately separated from her dad.”

“Every day they had to wake up at 4:30 am and stand for role call, which would take one to three hours,” Carly says. “Once, she saw the Nazis hitting her father. To dehumanize the Jews, the Nazis would humiliate them. They made him stick a finger in his ear, put his elbow on the ground and spin around in a circle. Mean-while, the Nazis were standing around him laughing.”

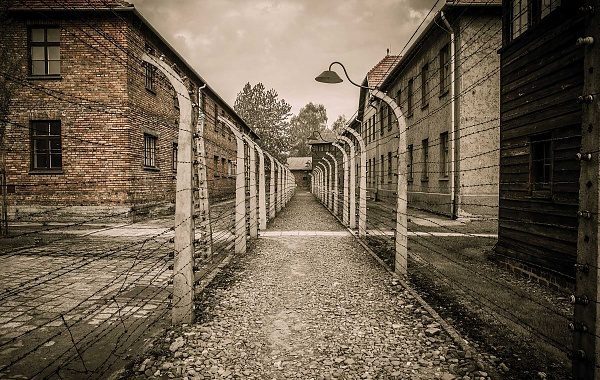

“What my grandmother called the worst day of her life was when her parents were called for transport. It was mostly the older people who were too old to work. She begged the Nazis to go with them, but they said she was too valuable and had to stay. She and her mother stayed up all night and cried and held each other. In the morning, her parents were transported to Auschwitz, where they were presumably gassed.”

While at Auschwitz, Lilo was sent with a group of women to the showers, waiting 36 hours for their fate to be decided. In the end, the Nazis decided they needed them to work and let them leave. She had dreaded a different outcome.

Lilo spent two years in nine concentration camps before being liberated by the Red Cross on May 4, 1945. “She went in with 1,500 people and came out with only 80,” says Carly. “She went in weighing 115 pounds and came out weighing 56. She was only 24 years old.”

Hans and Lilo in November of 2003.

Lilo and Hans ultimately married, settling first in New York before coming to Cherry Hill in 1991 to be closer to family. They had two children and four grandchildren. Hans died in 2005 at the age of 87. Today, Carly speaks to schools through the Goodwin Holocaust Museum and Education Center (GHMEC) in Cherry Hill, hoping to carry on her grandmother’s wish to be sure future generations remember what happened.

For Rachel Howe’s family, spreading that message is also a priority.

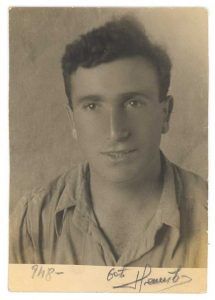

Growing up in suburban Cherry Hill, Howe’s childhood was idyllic. Her fondest memories are sitting on her grandfather Karol’s lap while he shared stories of his childhood in Poland during World War II.

She knew life was tough for this man she adored, but it wasn’t until she got older that she fully understood the horrors he faced as a Holocaust survivor. “He was always very vague about the details,” says Howe, 38.

Rachel Howe, holding her son Eli, often speaks with her grandfather Karol Strender about his Holocaust memories

Howe’s grandfather Karol Strender, 95, often shares his memories with his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren although he isn’t comfortable talking about the atrocities he personally faced. But he tells all he can so younger generations know what happened and learn from it. “We shouldn’t forget,” he says. “It’s as plain as this.”

Strender’s great-grandchildren are clearly learning. “While he never gives them the gory details,” says Howe, “they understand he had a very different life, a difficult life, but he survived it.”

This month, Howe will join her family – Karol, mom Tanya Buchman, 62; daughter Joey Rose, 5; and sons Dylan, 8, and Eli, 3 – in the March of Remembrance, a walk that raises money for the GHMEC.

Last year Howe learned about the walk and realized it would be special to make it a family affair. “One really great gift my grandfather has given me is a love for walking – he’s known at the Jewish Community Center as a man who, until very recently, would walk three miles a day,” she says. “It seemed like the perfect thing to do with him, and it was a short enough distance [about two miles] that I could do it with my kids.”

“We finished dead last last year! I was pushing my youngest in the stroller while my two older kids were getting frustrated with how slow I was walking with my grandfather, so they kept running ahead and then coming back.”

An earlier, undated portrait of Karol Strender has become a family treasure

Of course, that didn’t matter, Howe says. “For my kids, it’s so important that they hold onto their heritage. And for the younger generation who is not necessarily Jewish, it’s so important to look at this and think about tolerance, their behavior and their responsibility to the world. Where do you have to step in and say, ‘We cannot accept this behavior.’ We have to teach them that they have to look out for each other and for the world. This can’t happen again, yet it is happening again.”