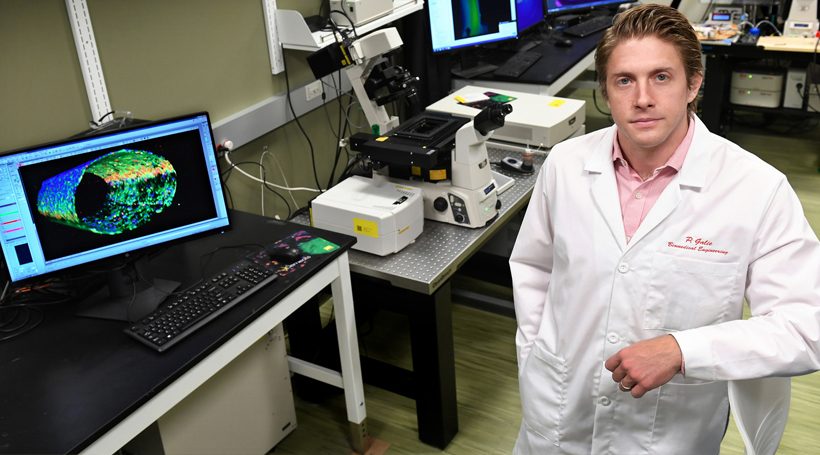

Pictured above; Peter Galie, Photo courtesy of Rowan University

One frustrating factor in the fight against Covid-19 is that so many questions have yet to be answered. The disease is so new, scientists are conducting research at the same time physicians are treating patients. It’s an unusual occurrence where findings are released piece by piece, the moment a study is completed. In South Jersey, healthcare researchers are all-in as they work to find answers to ease pandemic concerns.

Question: How does the coronavirus affect the brain?

One of the most concerning things about the coronavirus is that, unlike other respiratory illnesses, it has major neurological side effects in some people, including delirium and stroke. Even more concerning is the fact that sudden strokes are occurring in younger patients – people in their 30s and 40s who have otherwise minor symptoms but have tested positive for Covid-19.

In a lab at Rowan University, Peter Galie, an associate professor of biomedical engineering, is working to understand why. After months of research funded by a nearly $300,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Galie and his team discovered that the virus was physically shrinking the walls of cells in the brain and spinal cord, causing what he calls “leaks.”

“Blood vessels throughout your body are selective in what they let through their walls,” Galie explains. In the brain and spinal cord, cells are even more selective, forming what’s commonly called the blood-brain barrier. “The nervous tissue is much more delicate. Any time that barrier starts to break down, it can interfere with signals between neurons and cause neurological symptoms.”

The Covid molecule has spiky, crown-shaped proteins on its exterior, and by injecting those spike proteins into tiny blood vessel models and watching what happens under a microscope, Galie’s team has been able to figure out how the virus punches holes in cell walls, causing leaks and letting things into the brain that don’t belong there.

“A lot of the neurological conditions we’re seeing with Covid-19 we think are related to this breakdown and leakiness of the vessels,” he says. “The goal has been to figure out how it’s breaking apart that barrier, and then we can start to look at treatments to stop it.”

Question: Can we create a rapid, accurate Covid-19 test?

Most experts agree: until there’s a reliable, accessible vaccine for Covid-19, the best way to fight the pandemic is through constant testing. Unfortunately, that’s easier said than done. Most testing done in the first 6 months of the pandemic has required a medical professional to insert a long stick with a very soft brush on the end – kind of like a pipe cleaner – up the person’s nose and twirl it around for a few seconds. Then that’s repeated in the other nostril. The soft bristles collect a sample of secretions for analysis. That swab then goes to a lab, where a technician uses specialized equipment to test the sample.

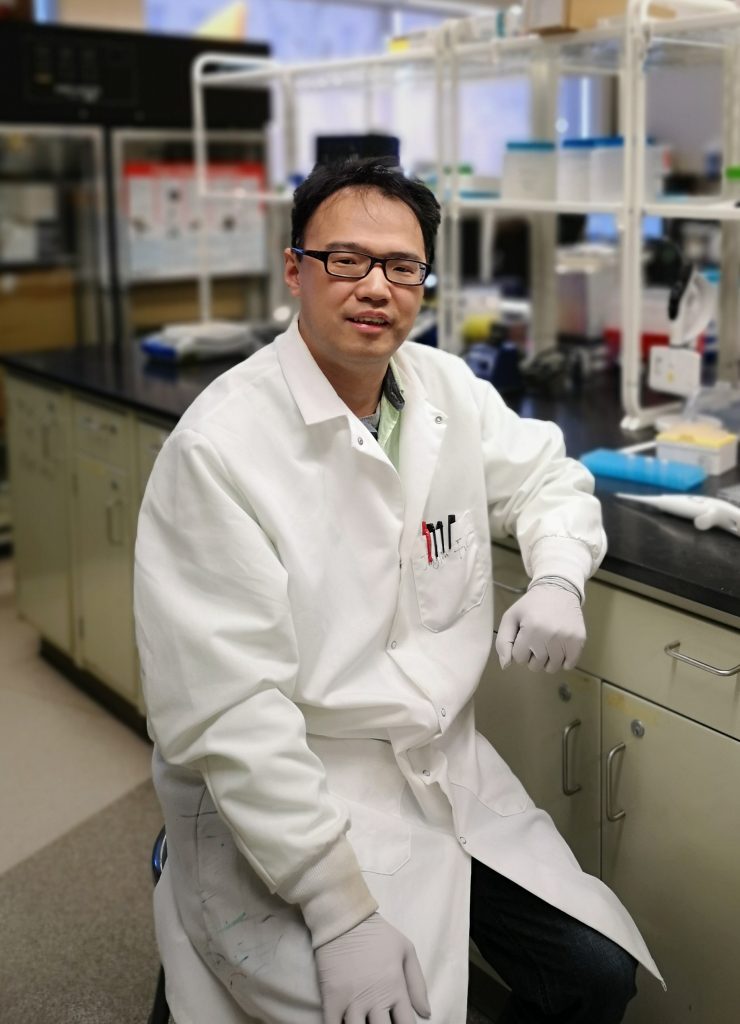

It’s a process that takes a lot of time and costs a lot of money, and that’s the problem Jinglin Fu, an associate professor of biochemistry at Rutgers University-Camden, is trying to solve.

Jinglin Fu

“There’s a need for a Covid-19 test that’s rapid and accurate,” says Fu. “That’s vital for reopening workplaces and schools, and keeping them open. At Rutgers, for instance, employees should be tested frequently to make sure the virus is well-contained. It also needs to be affordable. If you’re running many samples at the same time, it has to be cheap.”

The biggest way to cut costs is to create a test that doesn’t require a lab technician or the use of any specialized, expensive equipment. “We want to develop a method that does not rely on an instrument,” Fu says. “Just like a pregnancy test, where you can see the results based on the color of a strip; you don’t need a specialist to operate that.” And like a pregnancy test, he adds, the ideal Covid-19 test should have results that come back in minutes or hours, not days.

Fu isn’t aiming to create the first rapid test. In fact, that’s already been done – there are at least 4 companies in the United States producing tests that identify a specific antigen, found on the surface of the coronavirus, and can detect a peak infection in as little as 15 minutes. But such tests have shortcomings. They aren’t as accurate or sensitive as other tests, which detect the virus’ unique RNA sequence, but “take at least 10 hours and a technician in a lab,” says Fu.

His team is working to develop an RNA-detecting test that works much, much faster. RNA, like DNA, is a nucleic acid present in all living things. It acts as a messenger carrying genetic information. Based on patented technology that quickly detects specific RNA chains, the test would be able to use swabs – oral, throat or nasal – or blood samples and a paper strip to find even low-level infections.

For now, Fu’s research team isn’t identifying active Covid-19. They’re still working to develop the “reaction circuits” – or the pads on a test strip – that will identify targeted molecules.

Fu says the Rutgers rapid test likely won’t be available until 2021, but he also anticipates that it won’t be limited to the coronavirus. “It’s brand new technology that can also be used for other outbreaks in the future,” he says. “We’re not just developing a test – we’re developing a new approach for fighting a virus.”

Question: Does your risk of getting sick depend on what neighborhood you live in?

The coronavirus pandemic has impacted everyone, regardless of their age, race, faith or economic status. But data has shown that it hasn’t impacted everyone equally. A new study, led by Sarah Allred, associate professor of psychology and faculty director of the Senator Walter Rand Institute for Public Affairs at Rutgers University-Camden, finds a person’s community impacts their chances of dying from Covid-19.

Sarah Allred

“We are in the same storm, but not in the same boat,” says Allred. “We’re trying to understand how Covid-19 has progressed in different municipalities, and understand how it is also related to social structure and economic impact in a community.”

The study, which launched on July 1 and will run through the end of the year, is funded by a grant of over $18,000 from the Center for Covid-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness at Rutgers.

Ultimately, Allred says, the project will break down how the virus spreads through specific neighborhoods, and how that relates to availability of resources and income inequality. The more data and analysis that’s available, the better decision-makers will be able to understand the vulnerability and resilience of individual communities.

While Allred and her team are studying municipalities across the whole state, she says South Jersey counties acted differently during the pandemic’s early months.

“As cases were dropping in the North, they were rising in the South. In late April, early May, cases were continuing to rise in South Jersey,” she says. Part of the project is using the data to understand why, and to influence the way each of NJ’s counties handles health crises to come.

“We want to have a better map for making public policy decisions,” Allred says. “Now we’ll have a model of what happened so in the future we can say, ok, we can predict what’s going to happen.”