When Bill Leipold came home from Vietnam, he braced for a world that didn’t feel welcoming.

His family had hung a giant “Welcome Home, Bill” banner across the lawn of their Pomona house – a gesture meant with love, but out of step with the country he returned to. That tension hit immediately.

“I said, take that down,” says Leipold, a retired Army lieutenant colonel and helicopter pilot who served with the First Aviation Brigade.

And he was hardly alone. In “A Place of Honor,” a documentary from the New Jersey Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial and Museum, veterans describe similar unpleasant returns.

One veteran says he was given a hero’s departure only to return home and be treated “as a criminal.” Another remembers being told to hide his uniform because the protesters would blame him for the war. A pilot recalls surviving 100 missions over North Vietnam, then being called a baby killer within 24 hours of landing stateside. Again and again, they describe shutting down, going silent, trying to blend into a country that blamed them for the war.

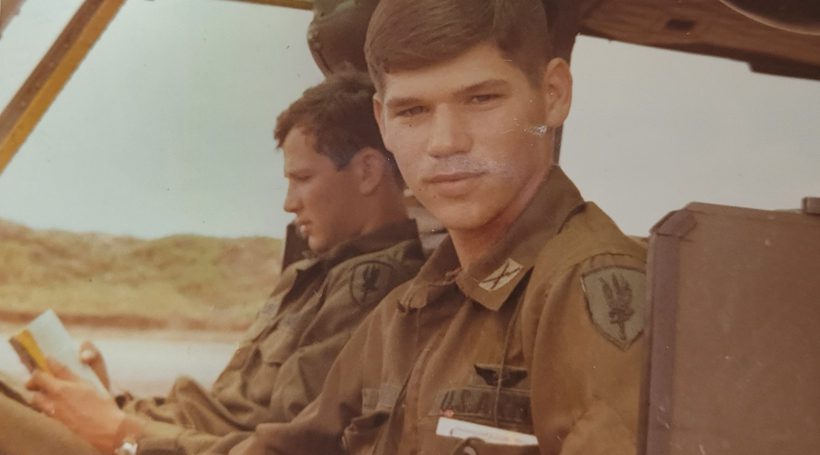

Bill Leipold and JJ Minor

The 30-minute documentary, recently screened with a red-carpet reception at the Scottish Rite Auditorium in Collingswood, features Leipold and fellow museum docents – all Vietnam veterans – as well as Gold Star family members sharing the stories they once felt they couldn’t tell.

The stories in “A Place of Honor” show how much of that history lived below the surface for decades. The veterans, now in their 70s, describe how young they were, how unprepared and how quickly the war changed them.

JJ Minor, who grew up in Atlantic Highlands and was drafted at 19, puts it plainly: “I never picked up a gun in my life. I was so far away down on the Shore, I didn’t even know where Vietnam was.”

He arrived during the Tet Offensive and was thrust into the worst of it. “I’d never seen a dead person in my life,” he says in the film. “My platoon sergeant grabbed my friggin’ neck and pushed my face down and said ‘get used to it.’”

There were countless moments like that – shocks that accumulated into something heavier, something he still carries. “Everyone that got killed, I know what they went through over there,” he says. “They went through the same thing I did, but they didn’t make it.”

Even now, with the family that came after his service, he thinks about how narrowly he survived. “I have 18 people now,” Minor says. “You always think, instead of making a left on that trail, if I made a right and I got blown away…I wouldn’t have had nothing and they wouldn’t be here.”

Since premiering in June, the film has screened at major festivals, won Best Vietnam Documentary Short in Beverly Hills and was selected for GI Film Festival DC’s Best of the Fest. It is currently airing on PBS stations around the country.

The New Jersey Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial & Museum in Holmdel exists, in many ways, because of that absence. In 1982, New Jersey veterans traveled to the national memorial in Washington and came home asking why their own state had no place to honor the 1,564 New Jerseyans who never made it back.

Former Gov. Tom Kean advanced the effort in 1986 by signing legislation to build a state memorial. A design competition drew some 400 entries, and the winning proposal came from Hien Nguyen, a Vietnamese refugee who had left South Vietnam 13 years earlier. By 1995, his vision had taken shape as an open-air circular pavilion of 366 granite panels – one for every day of the year, including leap year – etched with the names of New Jersey’s fallen.

Gov. Christie Whitman and General Norman Schwarzkopf attended the memorial’s dedication. The museum and education center followed in 1998, dedicated by Senator John McCain, himself a former Prisoner of War.

In the film, McCain’s words land with force: “Every veteran remembers those friends whose sacrifice was eternal. Their loss taught us everything about duty.”

For the veterans who now guide visitors through the memorial, those losses are never abstract. This has become the place where they reconnect – with each other, with difficult memories and the New Jersey names carved into its walls.

That sense of purpose is what drew filmmaker Vanessa Roth, an Academy Award winner known for her work with Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation, to the project. Museum CEO Amy Osborn recruited her to bring wider attention to these stories.

“Our mission is to honor New Jersey’s fallen heroes from Vietnam, preserve their memories, tell their stories and educate future generations about the Vietnam War,” says Osborn, a Cherry Hill resident. “We can never make it right for our Vietnam veterans, but I will die trying to do my part, to make them feel like the heroes they are.”

The legacy of Vietnam haunts each man differently, and Leipold carried his own version of it. He says he spent years saying little about Vietnam outside the company of other veterans. But he also points out that the Army – the path he chose because college felt out of reach, and he knew he would have been drafted anyway – ultimately opened every door that followed. Enlisting led to flight school, then to the leadership posts that shaped a 21-year distinguished military career.

When asked, Leipold says he will discuss the year he spent flying troops in and out of combat zones – long days navigating ground fire, hauling wounded soldiers and losing fellow pilots he’d grown close to in the intense pace of war. But the memory that stays nearest isn’t one of his own flights. It belongs to someone else.

George Carney, a childhood friend from Pleasantville, served in the infantry. “We were together from 3rd grade through high school,” Leipold says. Carney was drafted, went to Airborne School, and was killed in Vietnam August 28, 1968. For decades, Leipold didn’t know exactly how.

That changed when he began volunteering at the memorial.

On one of his first days shadowing Minor, Leipold stopped at the panel bearing Carney’s name. When he mentioned it aloud, Minor halted. “Bill, I was there the day he was shot,” Minor told him.

Another of his stops is the panel for James Gosselin, a Pleasantville native mistakenly listed as being from Pennsylvania. Leipold and one of Gosselin’s classmates helped set the record straight so he would be honored with the New Jersey fallen.

“I had to really do some investigative reporting on that to get that organized,” he says.

For him, guiding visitors through the memorial is a reminder of what his generation never received. Today, strangers will thank him for his service – a gesture he appreciates – but among Vietnam veterans, the exchange is different.

“What we Vietnam vets say to each other is welcome home,” Leipold says. “We didn’t get a welcome home. So that’s what we say now.”