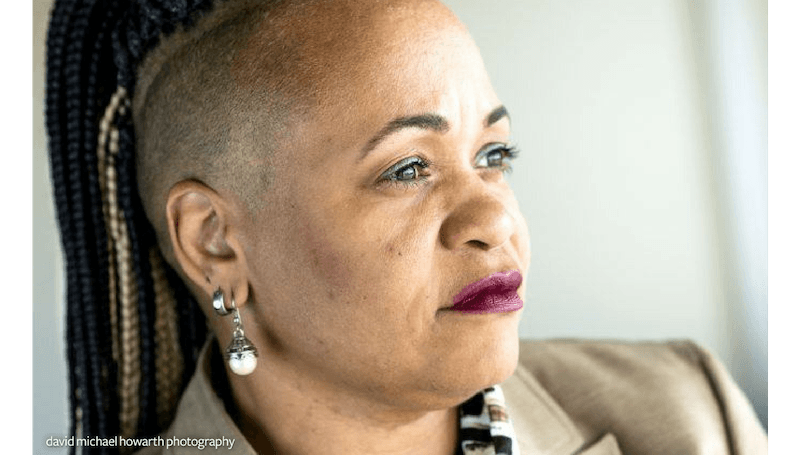

When she was under the grip of heroin addiction, Williamstown resident Kim Govak would sometimes leave her two young daughters alone while she scored the drugs she depended on to feel normal.

“I don’t think a mother who is not under the influence of opioids would consciously leave her children behind to go and seek out drugs for consumption,” says Govak, now in recovery. “But when you’re under the influence and you’re addicted, it’s like you really don’t have a choice in the matter. At least, that was my experience.”

It may sound cliché, but Govak, 51, never imagined she would sink so low. The reason she started using opioids was to deal with searing menstrual pain. Her doctor prescribed the powerful pills without warning there could be adverse repercussions. Hooked from the start, she only turned to street drugs when her doctor cut off her legal supply.

Both men and women may travel a similar road to addiction, but research shows that the opioid epidemic hits women differently, and in some ways much harder. They’re not only prescribed opioids for pain at a higher rate and given higher dosages, they also are at greater risk of developing a dependency. Moreover, recovery can be more elusive, often due to their role as caregivers, experts say.

While many factors come into play, biological differences in the way the sexes experience pain is a major one, notes Nathan Fried, PhD, assistant professor of biology at Rutgers University-Camden.

“Women are experiencing chronic pain at a much higher rate than men are,” says Fried, who studies chronic pain and the opioid epidemic. “They make up 65 percent of total prescriptions and are 40 percent more likely to become persistent opioid users following surgery.”

In addition, they’re typically given higher-strength dosages than a comparably sized man for the same effect, he says.

“There is some evidence that opioids don’t work as well in women as men for pain relief,” Fried says. “Women may have to have a higher dosage prescribed to them and at a higher rate. It could make them more likely to be exposed to dependency.”

Another biological difference has to do with hormones, which make women more sensitive to the effects of drug use, notes Richard Jermyn, DO, director of the NeuroMusculoskeletal Institute at Rowan University.

“It’s about metabolism, too – men and women metabolize drugs differently,” explains Jermyn. “Some of the data shows women may have more drug cravings and potentially a higher risk of relapse, even after getting into treatment.”

Depression and anxiety are also considered contributing factors that contribute to drug cravings. “There are higher rates of depression and anxiety in female populations,” Fried notes.

Until very recently, when the opioid addiction came into sharper focus both in South Jersey and nationwide, patients were often led to believe by their doctors that opioids were a safe option, Jermyn notes. And while the drugs remain viable for many people, for those with a genetic disposition to addiction, it can be a gateway to street drugs.

“We see a lot of women – moms – who sprained an ankle or hurt their back who are overusing Percocet, developing a substance-use disorder, and are then kicked to the street by a prescribing physician,” Jermyn says. “They’re told, ‘If you think Percocet worked, try heroin or fentanyl. It’s cheaper, and it’s just as strong.’ That’s the slippery slope.”

When they do get hooked, women are less likely than men to seek help, he says.

“Sometimes women don’t seek out medical care for themselves, but they make sure their family gets care,” he says. “They put their own health on the back burner. Or they’re afraid to seek out care. Men don’t necessarily have that concern; women do. ‘Child-protective services can come take my children. People are going to find out in my community. I’m going to be judged.’ That’s a huge barrier to getting care.”

Recovery can be more difficult for women, too, Jermyn says. “Women have a higher relapse rate than men do,” he says. “We have to realize that relapses are a part of the disease. And this is a really big gender issue: Moms don’t have the ability that men have for counseling. They may have children and no one to watch them.”

For Govak, then a young mother with a 2-year-old at home, it started with menstrual cramps. While the drugs took care of the pain, before she knew what was happening, she was hooked. Even after the cramps subsided, she continued seeking renewals from her doctor for years.

“I found I had access to them as long as I continued to manifest those symptoms, which were completely fabricated at that time,” she says.

After three years, Govak’s doctor cut her off, so she turned to street drugs. She knew she had a serious problem, but getting the help she needed was incredibly hard, even when it was available. She went for treatment 10 times over the course of a decade but didn’t truly begin recovery until 13 years ago, when her daughters were 10 and 11.

“My daughters were my motivating factor for change,” Govak says. “They played soccer and were part of karate, and I showed up for a lot of those events because I tried to keep up the semblance of normalcy. I tried. But I can’t tell you what state I was in. I got tired of seeing the pain in my daughters’ eyes.”

Today, as the director of the Center for Family Services Living Proof Recovery Center in Voorhees, Govak helps others who are going through recovery from opioids and other substances.

“I know that more often than not, recovery is not a linear process – relapse is real,” Govak says. “After a period of time – I can’t tell you when – I woke up and I no longer had the obsession to try to seek substances anymore, it was the first time my first thought wasn’t about trying to get a drug. And 13 years later, I consider myself still recovering.”