Once a month, a struggling group of moms meets to find strength, maybe even comfort, knowing that together they share an indescribable loss: the death of a child from drug addiction.

On the third Tuesday of every month, the club that nobody wants to join meets in Evesham’s RAP Room.

It’s a breezy spring night when five women – all club regulars – gather together in the welcoming meeting space on the grounds of the township’s Memorial Park. As the steady sounds of youth soccer practices and tennis volleys filter through open windows, the members joke about how they wish they’d never met. More seriously, they bemoan the fact that their group exists at all and are truly upset by the frequency with which new people enter their realm.

And yet these monthly meetings have become as essential to them as breathing. Their common bond: All are mothers who have lost a child to drug addiction. They sometimes refer to each other as “Angel Moms.”

The third Tuesday of every month is the one night these Angel Moms can be themselves, surrounded by others who understand that the hurt, pain, guilt, shame, love and anger doesn’t subside with time, even if some days become more manageable. As group co-leader Chris Weldon explains, their circumstance is simply incomprehensible to outsiders.

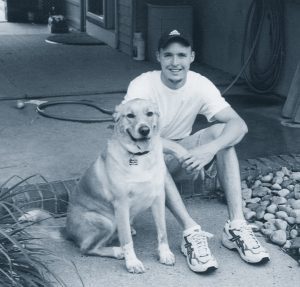

Ricky Jr.

“We’re every parent’s nightmare,” says Weldon, whose son Ricky Jr. died in 2003 at age 24. “People want to be supportive. You know they mean it when they try, but our situation is so unfathomable. You lose your kid to drugs first when they’re living, and then you really lose your child to drugs.”

It’s not just the death of a child they brought into the world and raised that is so incapacitating. There’s also pain in the collateral damage that comes with the territory, says Oaklyn resident Lucy Aquilino, whose daughter Melanie Gottschalk, 24, succumbed to a heroin addiction two years ago. Her body was found the day after her fatal overdose by the cleaning staff of a Woodbury hotel.

“There’s the fights, the legal battles, the stealing,” says Aquilino. “I’m not saying it’s any worse to lose a kid in any other way, but you don’t have all of that.”

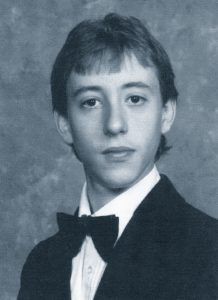

Louise’s Habicht’s son, John

For some, years separate them from their graveside goodbyes, while others in the club are experiencing major life events for the first time without their offspring. Co-leader Louise Habicht’s son John, 29, is the longest departed. Before he died in 2000, he warned his mother that heroin addiction was becoming an epidemic. “I thought he was being overly dramatic,” she recalls. John did not live to see how right he was.

Among the newer regulars, Aquilino starting attending meetings almost immediately after Melanie died. If it were offered daily, she says, she probably would have attended every meeting in that first year.

“I needed to be around people who understand,” she says. “Sometimes I don’t even need to talk. I just come, sit, listen and feel almost normal again. I can’t ever see myself not going.”

The group is run by Parent-to-Parent (P2P), an education, support and advocacy organization for parents of drug addicts. Supported through Evesham’s Community Awareness and Education Committee, P2P has been around since 1998, long before heroin addiction was deemed the state’s number-one health crisis – affecting young people once thought to be at low risk for addiction. It was founded by Habicht and three other mothers – three of whom lost their sons to drugs and one whose child has managed to remain clean.

By day, Habicht and other P2P staff continue to work tirelessly helping parents with issues they know all too well. The women provide advice on drug treatment options and legal needs, as well as emotional support. Over the years, they have helped place hundreds of addicts into detox centers, drug-addiction facilities or half-way houses and successfully lobbied several New Jersey governors to bring Daytop New Jersey, a drug treatment center for juveniles, to Salem County in 2005.

After years in which it seemed like them against the world, Habicht says it’s gratifying that advocacy, drug education and treatment options have grown exponentially in recent years. More people understand addiction as the chronic disease it is – all too often developed from exposure to legally prescribed painkillers – and not a result of bad parenting. Many realize now that anyone’s child could fall prey.

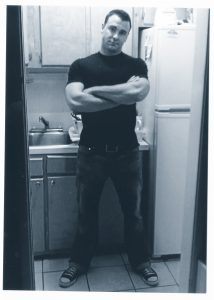

Adam Bush

“We feel we no longer stand alone,” Habicht says. “I somehow feel the loss of our children many years ago has made a difference for those who are now suffering and addicted. Hopefully the number of deaths will begin to be reduced due to new resources and awareness.”

Sadly, the current situation looks bleak. Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In New Jersey the heroin overdose death rate is more than triple the national average. Heroin fatalities now eclipse homicide, suicide, car accidents and AIDS as a cause of death in the state, according to a recent analysis by NJ Advance Media.

In 2015, 631 overdoses in Camden County resulted in 41 fatalities. So far in 2016 (through April 10) there have been 36 overdoses and one fatality. Even more promising, a new program called Operation SAL now offers survivors detoxification and intensive outpatient services – all paid for by the county – as long as the addicts are willing to enter treatment. But so far, only five or six of the 100 addicts offered the services have taken the county up on the offer, says Freeholder Lou Cappelli, who adds officials are currently working to develop better ways to identify addicts serious about getting clean.

By their own experiences, the “Angel Moms” say the drug epidemic shows no sign of weakening. They’ve come to expect at least one new attendee at each monthly meeting. Even more disturbing, the victims are succumbing at younger and younger ages.

“The damage has already been done to this generation,” observes Weldon.

At a typical meeting, there are rarely fewer than 12 people crammed into the RAP Room’s comfortable couches and seats. Regulars bring homemade treats and settle in for whatever the night brings.

When a new person shows up, meetings are typically a bit more reserved and structured, says Habicht. When it’s only regulars, there’s usually more laughter, but it all depends on who attends and how everyone is feeling. It’s OK to laugh, it’s OK to cry, it’s OK to tell stories about departed children that others in the outside world have long grown tired of hearing. And although some of the originals have stopped coming throughout the years, there are always new people seeking fellowship.

Timothy Marx

The group splintered from a longer established one that continues to meet on the first Tuesday of each month. That one is for parents whose children are battling addiction. However, when several regulars from that group lost offspring – but still wanted to attend the meetings – Habicht and Weldon realized the need for a new group.

“Having people whose children died mixed with the others wasn’t a good thing for the people who lost kids or the ones still fighting,” recalls Habicht, who first met Weldon at a candlelight vigil in Philadelphia years ago for children lost to drugs.

“I did it for selfish reasons,” admits Weldon. After Ricky died, she was one of the moms who needed the new group.

Still, in the beginning, it was hard to talk to other parents about children for whom help would never come, she recalls.

“Louise used to leave the room when new people came,” says Weldon.

“It used to make me angry that new people were coming,” Habicht says softly. “It still is upsetting to me.”

While the majority of participants are women, a few men regularly come as well.

“It’s different for the fathers,” says Maple Shade resident Michelle Bush, whose 30-year-old son Adam died Jan. 3, 2015. “I brought my husband once, but he couldn’t even speak. I think he knew he would break down if he talked.”

Like the group leaders, many regulars also belong to advocacy groups and organize events in their children’s memory to raise both awareness and funds to keep others from sharing a similar fate.

Sandy Marx, who just passed the first anniversary of her son Tim’s death in April 2015 at the age of 23, recently joined the New Jersey Addiction Recovery Public Advocacy leadership program. The Somerdale resident says she’s willing and eager to talk to anyone about the facts of addiction. Like so many, Tim didn’t fit the stereotype of an addict. For starters, his introduction to his drug of choice – Percocet – came by way of a prescription from his dentist after root canal surgery.

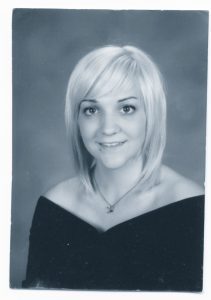

Melanie Aquilino

“He even told me the night before he died that heroin was not his drug of choice,” Marx says. “I hate when people say to me, ‘Your son is not suffering anymore.’ I don’t really believe he suffered. He was a happy-go-lucky kid. It just happened.”

Birthdays, anniversaries and holidays are hard for these women. Mother’s Day is particularly brutal because of all the hype and commercialism surrounding the day. Childless mothers are like the forgotten people, says Weldon.

“When you go to a store, people automatically say to you, ‘Happy Mother’s Day,’” she says. “I’m thinking to myself, ‘How dare you. How do you know it’s happy?’”

Bush notes that on Mother’s Day last year – her first without Adam, someone sent her flowers. The card said, “To mom, all my love, Adam.”

Through posting on Facebook, she found out the flowers were sent from a woman she works with who also sent them to other mothers who lost children.

“It freaked me out at first, but then it made me feel comfortable,” she says.

Aquilino was admittedly a mess throughout her first Mother’s Day without Melanie. “I found myself mad at people for not wishing me a happy Mother’s Day, but then mad when they did,” she says. “I didn’t even know what I wanted.”

The mothers who had more experience passing holidays without their children understood the conflict.

“We have to live their motto now,” says Weldon. “However you do it, it’s just one day at a time, just like they had to live their lives. It’s all you can do.”