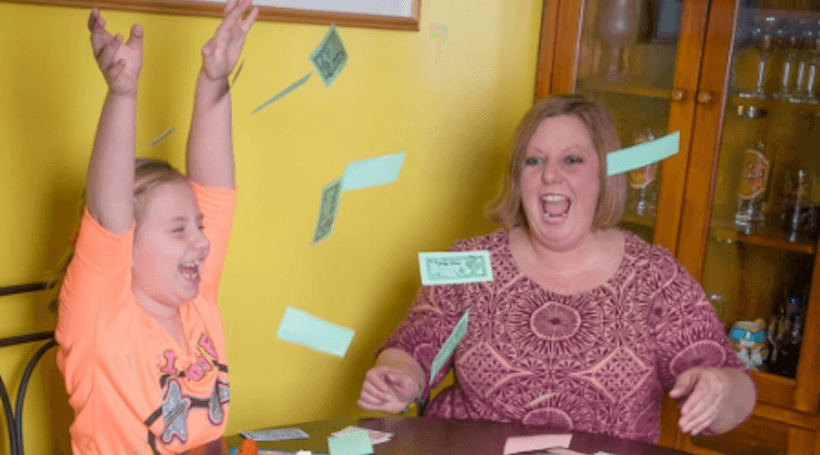

Kim Dunn was stunned, to say the least. The young mom was headed to the ER with a stomach pain that doses of laxatives couldn’t fix. A month and three surgeries would pass before she could finally leave the hospital. Dunn, at just 36, was diagnosed with colon cancer. Her daughter, waiting for her at home, was 3 years old.

“I had no idea. I thought it was a blockage, something that got stuck,” says the Blackwood resident, who is now 40. “Who would think it at 36?”

Hearing the words “it’s cancer” changes everything in the blink of an eye. It’s an unwanted moment that is affecting more men and women under the age of 40. Getting a diagnosis during the years when the foundations of life, such as career and family, are being built adds a complicated layer to the healing process.

“They have different needs than an older patient,” says Alexandre Hageboutros, MD, associate head of hematology/oncology at Cooper University Hospital. “Patients become concerned about having kids and getting married. There’s talk about banking eggs or sperm. There’s talk about not getting pregnant while getting treatment.”

The American Cancer Society estimates that only a small number of cancer patients are under 40, but the incidence is slowly increasing.

“There hasn’t been any specific, sudden influx,” says Richard Bleicher, MD, a surgical oncologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center who specializes in breast cancer. “It’s extremely rare under the age of 30, but it’s still disconcerting. We have women coming in who are in their 20s. Our youngest patient was 19. For most physicians, it’s never seen, never in their 20s.”

Robert Baumgartner was one of those rare cases. His testicular cancer was diagnosed in 2008 when he was 24. It numbered among the American Cancer Society’s anticipated 8,090 cases of testicular cancer that year.

“I was working out. I was feeling fine, not terrible. I was using the lavatory, and I found it then. I compared it to a marble,” says Baumgartner, now 28. “I knew it didn’t feel normal. I said to myself, ‘It’ll go away.’ It didn’t hurt, but I kept feeling like I should get it checked out.”

Robert Baumgartner

The Camden County resident went to his family doctor on a Friday. He sent Baumgartner for an ultrasound that day. The radiologist saw a solid mass, and the urologist knew during the physical exam that it was cancerous. A surgery was scheduled to remove Baumgartner’s right testicle so the mass could be biopsied. It was a long, whirlwind weekend leading up to the Tuesday morning operation.

“By Friday, I was told I had cancer. I never asked why. I asked if I could keep it, since I’d had it since I was a kid,” says Baumgartner dryly. “When I was told, inside, I felt out of it. I didn’t think it could happen to me. I looked it up, and I was in the prime age bracket to get this. I think about it and see the ramifications now. Then? I thought it was one of those things.”

Neither Dunn nor Baumgartner had much time to process what was happening to them or their bodies. Dunn went straight to X-rays and exploratory surgery back in 2008. She woke up with a colostomy pouch and 17 centimeters of her intestines gone. Twenty-four hours would pass before doctors determined the mass was malignant. It gave her time to think about how she would tell her daughter, Emily.

“At that point, I didn’t tell her too much,” says Dunn, a medical technologist at Cooper. “My parents brought her to see me. She was scared. I told her Mommy was sick. Now she knows about it.”

Baumgartner did not have children, but he had to decide during that long weekend if he would someday want them. He opted to bank his sperm before the surgery and the post-dose of chemotherapy, a moment he calls “the most awkward experience of my life.” Now he is engaged with a date set for November, but back then he got interesting advice about his pending social life.

“One thing the social worker told me was it might be more difficult dating. I was like, ‘more difficult?’ he jokes. “With my fiancée, Christine, it came up in conversation. She said, ‘OK, we’ll work through it.’”

Telling about a medical condition is just as personal as the condition itself. Some shout it from the rooftops as a survival technique; others keep it private. It was difficult for Baumgartner to keep his situation under wraps. He needed to take four days off from his job as a history teacher at Triton Regional High School in Runnemede, as well as a break from his master’s program in higher education and administration at Rowan University. (He graduated from the latter in 2011.) His absence was noticed, and the questions were quick when he returned.

“People were like, ‘What happened to you?’ I finally said, ‘I’m half the man I use to be,’” he says, deadpan. “People don’t always get my sense of humor. It’s how I got through it. You have to have the right frame of mind to get through it.”

Dunn prefers to play it close to the vest as well. She neither shies away from the curious, nor does she put her story out there. To her, it is just one part of her life.

“When I was first diagnosed, everybody wanted to know everything. Now it’s dwindled. It doesn’t come up that often,” says Dunn. “I don’t throw it out there. I don’t want it to be the first impression of me – ‘poor Kim.’ It’s a chronic condition, but it’s under control.”

About 13.7 million people were living with a cancer diagnosis as of 2012, says the American Cancer Society. That number is expected to jump to roughly 18 million by 2022. Five percent of survivors in the 2012-13 study were younger than 40.

“There is more of a survival rate than in the past. We are changing the face of cancer to a chronic condition, like heart disease, through treatment and control,” says Cooper’s Hageboutros. “It’s more intensive than a blood pressure pill, but it’s more controlled than 10 years ago.”

Just as the concept of cancer has changed, so have the weapons used in the battle against it. Genetic counseling and screenings are tools that are helping doctors get to the “whys” of cancer in patients under 40.

Risk assessment and genetic counseling piece together personal and family histories through a series of questions. A map of the patterns determines the likelihood of developing other cancers. If there is significant risk, then genetic screening, which is usually a blood sample, is the next step.

When a person under age 40 has cancer, Bleicher says, “The red flag is that it has a genetic component. It might mean genetic screening to tell us if they are at risk for other cancers. We will know to screen for that.” Bleicher uses the BRCA gene mutation as an example. It can be found in breast cancer patients but also indicates a higher risk for ovarian cancer. It is also linked to stomach, prostate and pancreatic cancers, says the American Cancer Society.

Dunn and Baumgartner each had a second round of cancer stemming from their original diagnoses. Cancer was found in Baumgartner’s lymph nodes, while Dunn is being treated for a spot on her liver. Each was found during routine follow-up scans. Neither is letting it stop their lives or their plans.

Baumgartner, who was 26 at the time, was given three months of radiation. He admits it was a difficult time, but it wasn’t because of worry over what the future might hold.

“Eating bland food was rough. I couldn’t eat the wings my dad makes, with all the sauce,” he says. “I did a condemned-man’s last meal the day before the first dose of radiation – cheesesteaks, a full slab of ribs, fries, wings, dessert. I told the dietitian and she said, ‘Did you throw up?’ I said, ‘No, I wanted more.’”

Dunn approached her situation with the same aplomb. Every other week, since the 2011 diagnosis, she heads to the Cooper Cancer Institute in Voorhees for a chemotherapy infusion that lasts four hours. She leaves with a pump that floods drugs into her system for 46 more hours, as well as an overwhelming exhaustion. She is able to work the week she is not getting her treatment, which will be a lifelong therapy.

“At the infusion center, everyone is on the same wavelength. There are seven or eight people I look for that I talk to. They are all in the same situation – lifers,” says Dunn with a laugh. “I try not to let it inhibit anything I want to do. As long as I am stable, I can skip a week, but not two months. I asked to skip a week because I wanted to do stuff with my daughter. We went to the Cape May Zoo and Storybook Land. I live with cancer. Cancer does not rule how I live.”