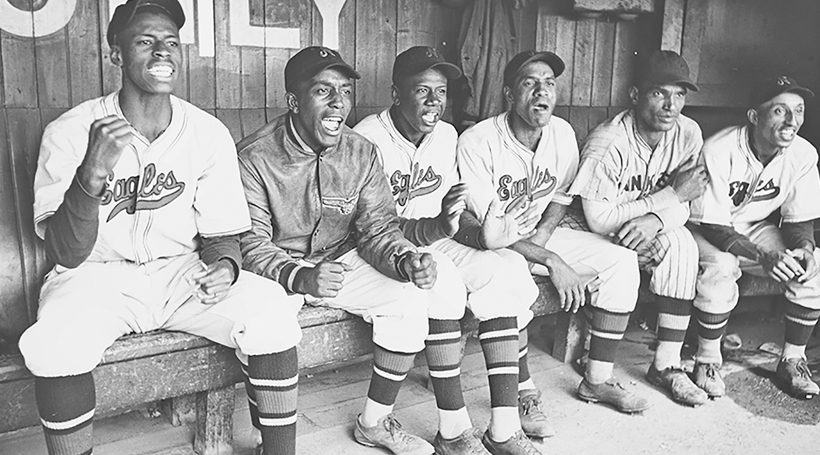

Max Manning (far left) and his teammates on The Newark Eagles in 1939, photo: Yale University Library

Max Manning was a star pitcher for Pleasantville High School, and when the Baltimore Orioles wrote to say they were sending a scout, he dreamt about a future on Baltimore’s Major League Baseball team. For Max, that particular dream was short-lived.

“My grandfather told him, ‘They don’t know you’re Black,’” says Belinda Manning, Max’s 72-year-old daughter. “They came, found out, and that offer went away.”

It was the 1930s, and Max was the only Black player on Pleasantville’s team. In fact, Manning says, her dad was one of the only Black students in the school. After high school, Max went to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania.

“His father and his grandfather went to Lincoln,” she says. “So he was going to go there. He was going to be a doctor.”

Max couldn’t give up baseball, though – he and his roommate Monte Irvin played together on Lincoln’s team. Before graduation, they tried out for the Newark Eagles, made the team and left college early.

The Eagles were one of the best teams in the Negro League, which formed after professional baseball was officially segregated in the late 1800s. By the time Max and Monte joined the team, the league was thriving, with Philadelphia and South Jersey at its center.

“There were some 30,000 African Americans living in Atlantic City,” says Ralph Hunter, founder and president of the African American Heritage Museum of Southern New Jersey. And baseball was a big deal. “Everyone wanted to come to Atlantic City in the summertime for baseball games. People came from all over to see the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants play. You’d get up on Sunday morning, go to church for 11 am service, then everyone went to the baseball field. After the game, there was a parade. It would start on Adriatic Ave., go up Virginia Ave., and come up Arctic. That happened every weekend.”

The Giants were named for Harry Bacharach, a 3-time mayor of Atlantic City. They were a popular team when they were added to the Negro National League in 1920, says Bob Allen, who teaches a course on the history of Black baseball at Stockton University.

“Mayor Bacharach and the other local politicians were interested – at least in part – in keeping Blacks off the boardwalk on Sunday afternoons,” he says, “and so they gave them baseball. If you really want to understand the United States, you have to understand baseball. It sounds hyperbolic, but it probably isn’t.”

As America diversified, Allen says, baseball erased cultural prejudices. “Of course, it was a great assimilator for everyone but African-Americans. Somebody could make the mark for you in baseball. Hank Greenberg was Jewish. Italians had Joe DiMaggio. But people of color were told, ‘We won’t let you play, and you can’t play anyway.’ So, they did the obvious; upheld the American tradition of rebellion.”

By the 1920s, teams filled stadiums in the Northeast, the Midwest and the South. The league hummed along, gaining popularity through the ’30s and into the ’40s.

“I remember going with my parents to Leniel Hooker’s bar in Newark – he’d played with my father. They’d all joke about Crazy Ray Dandridge, and my dad’s best friend was Leon Day. When you think about the bond that was forged… think about steel; when you put it in fire, it gets stronger.”

“One thing I learned from my father and the men of the Negro Leagues is that you’re capable of creating your own reality,” Manning says. “You don’t have to subscribe to what people are telling you is the reality. You can create something different. These guys were just going to play ball. They were going to play the best ball they could, which was better than most. They were not going to be denied the right to play ball. The creation of the Negro Leagues, when you think about the imagination and the determination it took to create that, is an incredible thing.”

A few years after Max Manning joined the Newark Eagles, the United States entered World War II. “A lot of the men, including my father, ended up going to war,” Manning says.

Max served in Europe with the Red Ball Express, a famous transportation convoy, staffed mostly by African-American soldiers, that moved Allied troops from Normandy across Europe.

Max returned in time for the 1946 season. The Eagles beat out the Kansas City Monarchs to win the Negro World Series, and Max won Pitcher of the Year. He and Monte Irvin were stars.

In 1947, Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers, beginning the integration of MLB. The Negro Leagues began to wane, and the tactics of the major league clubs didn’t help.

“What happened was there was a lot of raiding taking place,” Manning says. “Major League Baseball would offer money and contracts to players without buying out the contract they had with Black owners.”

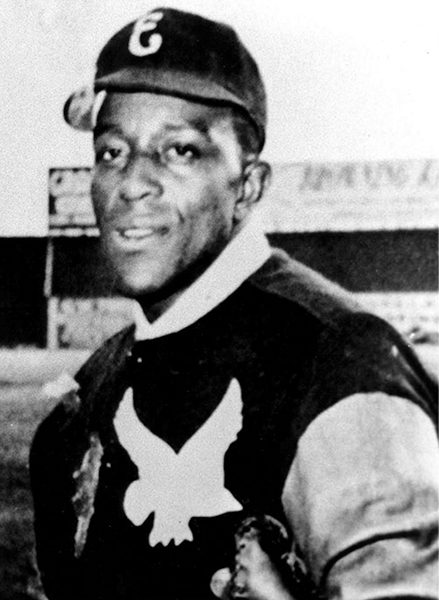

Leon Day was inducted into the baseball Hall of Fame in 1995

Ray Dandridge and Monte Irvin went. So did Leon Day, Smokey Joe Williams, Roy Campanella, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Satchel Paige and many others.

In 1957, Philadelphia became the last team in the National League – and one of the last teams in the majors – to integrate. Far too late, in Max’s opinion. “In my house the Phillies were always referred to very specifically,” Manning says. “I never knew the name of the team wasn’t ‘Those Damn Phillies.’”

The Negro Leagues sputtered for a few years, then blinked out. Max came home to Pleasantville to raise Manning and her siblings, and spent the next 33 years teaching 6th grade, coaching baseball and working for the town’s recreation department.

“We had 4 playgrounds in Pleasantville when I was growing up in the ’50s,” Manning says. “He was the recreational person at playground Number 3. Baseball was some of the greatest times of his life, but he was a teacher. Those years in the classroom, educating us and all the other kids in town, were the most meaningful to him.”

Manning says the former players remained close all their lives.

“They were so warm, so engaging – to know them was to love them. They all played on different teams, but later in their lives they stayed close friends. I remember going with my parents to Leniel Hooker’s bar in Newark – he’d played with my father. They’d all joke about Crazy Ray Dandridge, and my dad’s best friend was Leon Day. When you think about the bond that was forged…think about steel; when you put it in fire, it gets stronger.”

In the 1990s, there was a resurgence of interest in the history of the Negro Leagues. Max and his teammates traveled all over the country, Manning says, attending All Star games, Hall of Fame inductions, and other events. In 2001, Allen asked Max, then 82, to do an on-camera interview.

“After a 2-hour interview I was overwhelmed by what they’d gone through,” Allen says. “That triggered something in me. I just knew that I would have to interview as many of these players as I could and devote as much time and energy as I could.” He spent the next few years crisscrossing the country, recording the oral histories of nearly 200 players.

Max died in 2003. But in Pleasantville, where Manning still lives, her father’s legacy is cemented. “Of those 4 playgrounds we had, only one is still a park today,” she says. “Playground Number 3 has become Max Manning Complex. All the sports in the city are played there. He’d be very happy about that.”

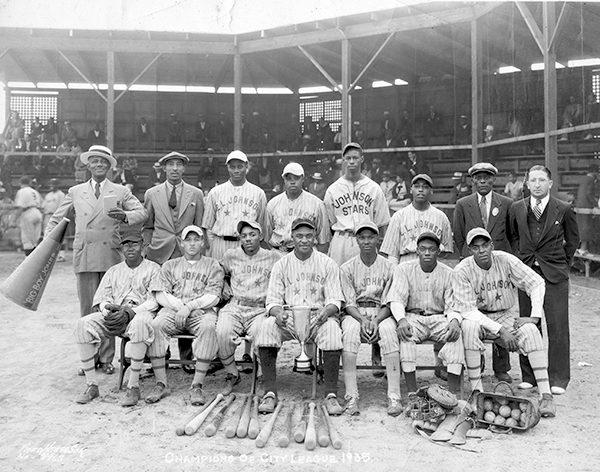

Max Manning played for the Johnson Stars as a teen. (He is the tall player in the back row, 4th from the right.), photo: Atlantic City Heritage Collections, Atlantic City Free Public Library

She’s less sure how he’d feel about this: In December, MLB announced they were “correcting a longtime oversight in the game’s history” by elevating the Negro Leagues – dozens of teams that played in cities across the country between 1920 and 1948 – to major league status. Of the thousands of men who played in the league throughout its history, fewer than 150 were still alive to see it recognized.

“When it was announced I got a call from Leon Day’s widow,” Manning says. “She said, ‘I know you heard this, I know you know what’s going on. Listen, all those guys are dead. And what happened, happened. And if you are trying to relieve your conscience through me, you’re going to have to get that from someone a little higher than me.’”

Plus, she adds, it feels a bit unnecessary – like a confirmation of something they’d always known: they were professionals. Major leaguers all along.

Still, she hopes it keeps people talking about the Negro Leagues, and that as their dynamic tale is told, the conversation will expand. There’s so much more untold history to acknowledge and honor, she says, and baseball is just the beginning.

“It’s not just about the Negro Leagues,” she says. “They are an exemplar of all the other untold stories.”