Photo: David Michael Howarth

Football was Preston Brown’s ticket out of Camden in the early 2000s. But it was also the reason he returned. His incredible story – of poverty, struggle, commitment and success – caught the attention of a producer at NFL Films, who created “Camden Comeback,” a tale of a coach, and a city, who never stop fighting for things to get better.

Preston Brown didn’t realize how different the world was outside of East Camden until he was around 11. That’s when a drug dealer on his street signed him up to play football.

Preston Brown didn’t realize how different the world was outside of East Camden until he was around 11. That’s when a drug dealer on his street signed him up to play football.

“He said ‘Listen man, I’m going to sign you up to play at Pennsauken Youth Athletic Association,’” says Brown. “He was like, ‘You can use my grandmom’s address. Just don’t tell anyone or they won’t let you play.’”

Brown, now 35, was one of 6 kids being raised by a single mom. “At the time I started playing football, we were borrowing electricity from the neighbor’s house with an extension cord,” he says. “We couldn’t use our front door because there were guys dealing on the steps. We had to go around back. I didn’t even see that as a rough situation. It was just life.”

But in Pennsauken, among his teammates, things were different. “Every one of those Black kids I played with on that team, they had a mom and a dad. They lived in a house,” Brown says.

“None of us in Camden had dads that lived at home with us. It was mom, grandmom, aunts. There were no male figures. It was amazing to me that we could be living blocks away and have completely different lives. Like why is it that I can walk to where they are, and there were things I’d only seen on TV.”

Photo: David Michael Howarth

Eventually, of course, Brown’s secret came out, and the team’s leadership discovered he didn’t live in Pennsauken. “Coach Rob Davis came over and was asking me questions and I thought this is it, they’re going to kick me out,” Brown remembers. “He was like listen…I also live in Camden. You be on the corner at 5:15 every day we have practice, and I’ll give you a ride. If you’re not there, I’ll keep going. Every day for 2 years at 5:15, I was on that corner.”

The Pennsauken youth team went on to win a championship, and private high schools around South Jersey began recruiting Brown as he came out of middle school. He turned them down. “My whole entire life was in East Camden,” he says. “All I ever wanted to do was play for the Tigers.”

So he did, lettering 3 years straight at Woodrow Wilson High School. And like so many of the city’s best and brightest of the time, Brown left his hometown. He went on to an illustrious college football career, flirted with the pros, and started his own family. But in 2015, he came back to Camden to right a then-sinking ship, and within 3 seasons the Tigers were a championship team, and Brown was a household name in Camden again.

To James Weiner, an NFL Films senior producer who was tracking the Tigers’ ascent, what he knew of Brown’s life read like a movie script – one that he wanted to produce if only he had the time.

“I’d been following the Woodrow Wilson story,” says Weiner, a Haddonfield resident. “In 2012, they go 0 and 10. In 2018, they finally break through and win a championship. In 2019, they win again, and at this point I’m like boy, I really blew the opportunity there.”

He had made peace with throwing away the shot when, in February of 2020, a chance encounter between the 2 men in a Mt. Laurel sub shop changed his mind.

Weiner was hanging around waiting for his sandwich when Brown walked in. “He’s larger than life, and I recognized him right away,” he recalls.

Weiner introduced himself, telling Brown he regretted that NFL Films hadn’t produced a story on the team in 2018 or 2019.

“He said ‘Well, you got time to sit down now? I’ll tell you my story,’” Weiner says. Even the short version of it was fascinating, Weiner recalls.

“I thought wow…not only is it a better story than I imagined, but the way he tells it makes it made-for-TV,” Weiner says. “I said ok, let’s bring in NFL Films. I’ll recreate the Woodrow Wilson locker room in one of our studios, I’ll just interview you and we’ll see what happens. It ended up being like a 3-hour interview.”

The final product is a 20-minute feature that aired nationally last December and still streams on NFL Films’ website. It weaves Brown’s life and the teens on the football team with the story of Camden, following the Tigers through a football season that was abbreviated into just 6 games by the pandemic.

In the film, Brown is up-front about things like seeing his mother cook crack in the family’s kitchen. He’s humble yet candid about his own success. He was class salutatorian at Woodrow Wilson and had 31 football scholarships coming out of high school, he says, including full academic rides at places like Stanford and Notre Dame. But it was New Orleans that felt like home.

“Tulane University is in probably the richest community in the city,” he says. “But you can go 10 blocks up and be at the Magnolia Projects, and I was like man, this reminds me of Camden.”

Brown attended Tulane from 2004 to 2007, but his journey was almost derailed when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005. Along with his teammates, Brown was evacuated to Jackson, Miss. with just a duffel bag and his football gear. For days, they slept on classroom floors in a school that had been converted to a shelter. They were told the Tulane campus – and their football field – were underwater.

“I never really had a bed growing up, so sleeping on the floor was just a regular thing for me. I was fine,” says Brown. “But a lot of the seniors started saying, ‘Look, let’s call it quits, let’s all go home.’ I was like listen dude, I’m not going back home to sleep on the couch. I can’t be walking around Camden with no job, no money, no scholarship, no nothing. I don’t have anything to go to. And these people on our team, from New Orleans, they don’t have anything to go home to. We need to play.”

That season, Brown earned Third Team All-Conference USA honors, started all 11 games and led Tulane as a receiver with 47 catches, 720 yards and 6 touchdowns. By the time he graduated in 2007, he’d become team captain, met his wife and had his first child.

“The day of graduation I got a call from the head coach of the Buffalo Bills,” Brown says. “He said, ‘You want to play football?’ I said yes. He said, ‘You need to be in Buffalo by 9 pm tonight.’ I was like it’s 2:15, I’m walking down the aisle for graduation, and I’ve got my now-wife and my daughter here. Here goes Preston with another dilemma.”

With the encouragement of his family, Brown got on the plane. The Bills eventually waived him, and though the New York Jets expressed interest, he didn’t make that roster either. Brown ended up playing with several start-up football leagues, including the Philadelphia Soul in the briefly lived Arena Football League (AFL).

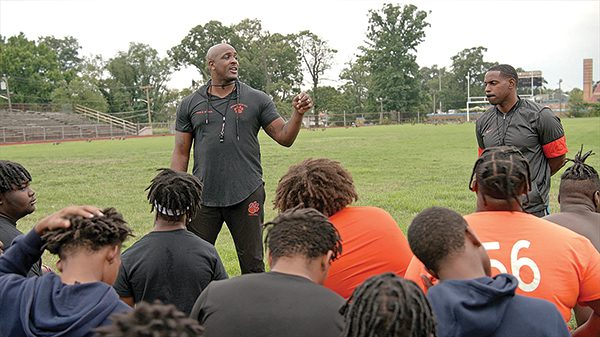

Coach Preston Brown with the Woodrow Wilson High School football team, photo: NFL Films

When the AFL shuttered in 2012, the same year the Woodrow Wilson Tigers failed to win a single game, Brown went back to school, finished his master’s degree in education and, finally, came back home.

He was hired as the team’s head coach in 2015, and started building his staff. “The first guy I called was Coach Rob.” That’d be Rob Davis, the football coach who drove Brown to practice in Pennsauken all those years ago.

Together, they’ve weathered tragedies, including the murders of Brown’s brother and Davis’ son. “We’ve lost kids from the team and from the school,” Brown says. “Over the years it’s been 6 or 7 students. It’s not normal. It’s not one of those experiences you ever get used to.”

And yet, the team and its coaches persevere. And that’s the message of the film, of Brown’s life, and of Camden’s comeback story.

“There’s a certain resilience in that community, and it’s evidenced by Woodrow Wilson football and Preston Brown,” Weiner says. “For years, if you grew up in Camden the goal was to get out and never come back. Preston came back, and the message is you can make a life for yourself in Camden.”

And Brown’s message has made its way well beyond Camden’s city limits. The NFL Films feature is nominated for a Sports Emmy, and in January he received the 2021 Congressional Camden County Freedom Award. Brown’s doing more than teaching kids to play football. He’s creating opportunities for kids just like him to shape the future of the city he calls home.

“People like me, and people I grew up with in my community, we were taught it was us against the world,” he says. “People knew Camden as a negative place, and I always wanted to change that narrative. The young people we send out into the world, to these colleges, to become great and productive citizens – they are the ones who change it.”