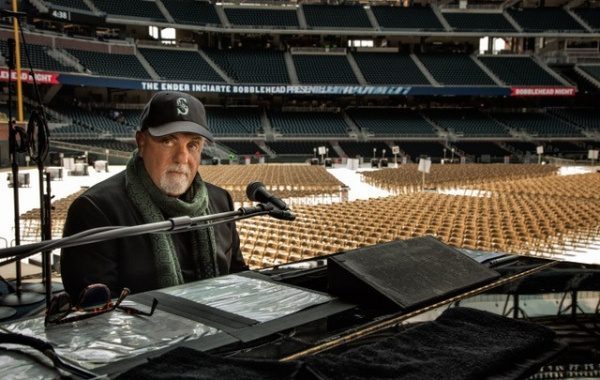

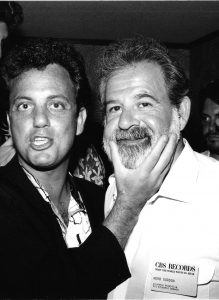

Billy Joel and Cherry Hill’s Herb Gordon

When Billy Joel comes to town, the Piano Man is showered with a type of love that is typically reserved for a hometown hero. And like he did last month during his show at Citizen’s Bank Park, the mega star always reciprocates. In fact, Joel has his own Philly Special, a crowd favorite he will rarely – if ever – play live. The song is “Captain Jack,” and he’ll play it when he comes here.

“We only do that song in this town,” Joel says. “You’re sick and twisted people. But we like it.”

“Captain Jack” was one of Joel’s earlier hits that talks about a drug dealer in Long Island, where Joel grew up.

“Captain Jack isn’t Jack Daniels. I used to live near the projects in Long Island and there were drugs going on and the dealer was called Captain Jack,” Joel writes on his website. “There was also smack. They used to use the rhyme for smack, Captain Jack. So I didn’t mean it to be any specific drug, it’s whatever people had to take to escape reality. It was drugs in general. You know I call it a look-out-the-window song. I was just looking out there and seeing all my friends, everybody would just get their brains wasted and fried and I thought it was kind of stupid. We were in the suburbs – what are you junkin’ out for?”

Despite the song’s edgy content, many say it started a long and successful career – thanks to the intervention of an influential South Jersey promoter.

It all began in the early 1970s when WMMR-FM was first to broadcast “Captain Jack,” airing it even before it appeared on any of Joel’s albums. (Philly promoter Dennis Wilen convinced Joel to record the song for a series of concerts for the rock station. See sidebar on page 63.)

Each airing of the track on ’MMR – to which Joel tacked on the phrase “except Phil-a-del-phi-a (with “phi” rhyming with “fly” and a long “a”) to the end of the line, “There ain’t no place to go anyway” – resulted in an unusually high volume of calls from listeners demanding an encore and wanting to learn more about the artist. It was a phenomenon the likes of which Philly radio had never experienced, and it caught the attention of a music industry insider who lived in Cherry Hill – Herb Gordon.

Known throughout the business as “Herbie,” the well-liked promoter was working for Columbia Records to get the label’s new releases in front of radio station programming executives and on-air personalities.

Gordon, who died in 2007, took note of the unusual demand for “Captain Jack” and talked it up to his colleagues at Columbia’s Manhattan headquarters. This was around the same time that Joel, who was unaware of the hubbub he had created in the Delaware Valley, left for Los Angeles to perform in a piano bar under the pen name “Bill Martin,” a tale he subsequently immortalized in “Piano Man.”

Columbia’s interest resulted in Joel signing with the label, launching his career in earnest.

Gordon’s daughter, Tammy, had a unique vantage point in Joel’s early days. While her dad worked with countless artists – from those who never escaped obscurity to Johnny Mathis and Bruce Springsteen – Herbie saw Joel as something special, the Collingswood resident recalls.

“I distinctly remember my dad talking about Billy Joel and saying, ‘This guy’s really great,’” Tammy says. “He kept telling me how important it was to listen to him, and that he was going to be so amazing.”

“And I was thinking, all these other stars have such interesting names and ‘Billy Joel’ sounds like somebody who might have gone to Hebrew school with me. But he said, ‘No, he’s going to be big. He’s really going to be big.’”

Even when Joel had achieved global superstardom, he never forgot where it all started. Tammy recalls going backstage with her father after one performance at the old Spectrum in South Philly and Joel saying to them, “I love Philadelphia!”

Nor did he ever lose his affection for her father or forget the promoter’s early advocacy on his behalf.

Nor did he ever lose his affection for her father or forget the promoter’s early advocacy on his behalf.

After Herbie died, Joel wrote a letter to Tammy, her two sisters and their mother. It read:

Herb Gordon was a real music man in an industry often characterized by hype, politics and corporate interests. Herb was a true aficionado of the art of recording, songwriting and performing. He took a personal interest in artists who he represented, and somehow managed to familiarize himself with all the tracks on their albums, not just the radio-friendly ones.

Herb was always there for me whenever we played Philadelphia, Eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey. His devotion and support were boundless, and his longtime friendship with friends and colleagues was a testament to the affection and respect we all had for him. He represented an archetype that no longer exists in the music business today. He was a hands-on person, follow-through guy, the kind of man that we refer to as a mensch. I know I will miss him and the wonderful energy that he always had when he welcomed us to the City of Brotherly Love.

Aside from his NYC concerts, Joel visits the City of Brotherly Love more than anywhere else. In fact, last month’s gig marked the sixth consecutive year he’s played Citizens Bank Park. And, earlier this year, the venue announced the creation of a “musical franchise” for Joel. A first for both parties, the franchise sets up a residency for Joel. In May, in the days leading up to his last concert, the Phillies stadium set up a special kiosk selling tour merchandise during Phillies games and other times.

Joel also has a residency at Madison Square Garden, and those monthly concerts still sell out. (His next is July 11.)

Don’t call it a casino gig

During an early-1990s press conference in Center City Philadelphia, Billy Joel was asked by a reporter why, unlike the Rolling Stones and numerous other rock superstars, he had never played at an Atlantic City casino. In response to the question, the beloved singer-songwriter described the seaside gambling mecca as “an elephant’s graveyard for entertainers” and made it clear he’d never play there.

On the surface, it’s a promise he’s kept, as he has never done a public performance there. But that doesn’t mean he’s totally a man of his word.

On July 21, 2007, Joel and his band performed for more than 2,000 invited guests at the Event Center at Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa as part of the resort’s fourth anniversary celebration. Joel, who was reportedly paid $1.5 million for his efforts, turned in a full set that was typically heavy with signature songs including the show-opening “My Life,” “Just the Way You Are,” “Don’t Ask Me Why,” “We Didn’t Start the Fire” and “Piano Man.” – Chuck Darrow

That song on the radio

When South Jersey’s Herb Gordon first heard Billy Joel sing “Captain Jack” on WMMR-FM, he was hearing an intimate concert that young promoter Dennis Wilen had put together. Wilen’s concert series featured up-and-coming artists including Bonnie Raitt and Todd Rundgren.

On a trip to NYC, the independent promoter learned about Joel during a visit to Family Records, the musician’s original label, and heard “Captain Jack,” a new song about suburban teens using drugs to escape reality.

“I thought it was relatable, specifically to the 18-to-34 demographic, which is what we were looking for,” Wilen says. “It wasn’t like Carole King, and it certainly wasn’t Cat Stevens. There was something new and fresh about it.”

“There was no Bruce Springsteen at this point, but here was a kid that was talking about hanging out in the parking lot, living at home and smoking pot. And it was relevant and down-to-earth.”

Wilen knew he wanted to include Joel in the concert series, but he had to convince the station and, more importantly, Joel.

By this point, the musician was disillusioned with the way his career as an aspiring singer-songwriter was going. His 1971 debut album, “Cold Spring Harbor,” was a bust. It had garnered little notice from the public and was all but ignored by the radio stations.

And from an artistic perspective, he had concerns. Among them, during the process of transferring the recorded material to vinyl, the tape was played too fast which, Joel was once reported to remark, made him sound like “one of Alvin and the Chipmunks.”

But Family Records was excited. And Joel agreed to perform. That concert, when aired on WMMR, caught listeners’ attention, as well as the attention of one South Jersey promoter. And the rest, well you know what they say. – Chuck Darrow