Six years ago, Camden had the highest crime numbers in the state, a murder rate that rivaled some third world countries, and 175 open-air drug markets. Then, the city fired all its cops.

Six years ago, Camden had the highest crime numbers in the state, a murder rate that rivaled some third world countries, and 175 open-air drug markets. Then, the city fired all its cops.

When Camden County Freeholders proposed dissolving Camden’s 141-year-old police department and replacing it with a county-run force, the move was loudly criticized across the country.

But the Freeholder’s plan had a purpose. For decades, the police department had been plagued by scandal and corruption. At one point, it had five chiefs in five years. And expensive union contracts, officials explained, were making it financially impossible to give Camden what it really needed: more officers on the street.

As the Camden County Metro Police Department (CCPD) was formed in the spring of 2013 – a process that involved both re-hiring some of the laid-off officers and training dozens of new recruits – the community remained skeptical.

“It was a very tense environment,” says Felix Moulier, a Camden native who served on the Public Safety Board during the transition from city to county force.

“There were two sides: one who wanted their local police department and others who wanted change. Change won out, and most people don’t like change at first.”

But the CCPD has proven that, sometimes, a radical solution works. Between 2012 and 2018, Camden’s murder rate fell by nearly 70 percent. Crimes like burglary and arson decreased by more than half. Last year, the city had fewer total crimes than in any year since at least 1974. The number of drug markets has plummeted to below three dozen.

The biggest difference from then to now is the increased police presence on city streets. Before the change, there were some 270 police on the city force. The 400 officers on the CCPD force today spend the majority of their time on the street, walking neighborhood beats and working to create an environment that’s not conducive to violence and drug dealing.

“I used to witness it,” says Moulier, whose skepticism about the new department has turned to admiration. “When I lived in North Camden, the addicts were my alarm clock, walking to get their drug of choice. Now you go to North Camden and all you hear are kids playing.”

At the vanguard of this change is J. Scott Thomson, who joined the city force in 1994 and was tapped for the chief’s job in 2008. When the new force was formed, Thomson stayed in the role.

“I think the Attorney General looked around the room, and I was the only one who wasn’t going to be indicted in the next six months,” Thomson jokes. “For the next year and a half, they kept interviewing other people to potentially replace me. They didn’t put me in the position with the intention of keeping me for the next decade.”

From the beginning, the newly-created CCPD ushered in a new culture. It embraced technology, using forfeit funds from criminals as well as county grants to purchase eye-in-the-sky surveillance cameras and specialized shot-spotter microphones. The new technology immediately detects criminal activity, so officers can be dispatched before the department receives a 911 call. Thompson’s main priority, though, was shifting the department’s cultural identity. The police shouldn’t be warriors, he says. They’re supposed to be guardians.

“The people wanted their officers to be mentors and facilitators, to work with the youth and not chase them,” Thomson says. “We couldn’t just show up thinking we could fix every problem with a pair of handcuffs. It was about getting officers out of their squad cars. If the only time they’re engaging with the community is in moments of enforcement or crisis, that’s the lens through which the public identifies the police. And worse, it becomes the lens through which the police define the community. We can’t arrest our way to a safer city. We needed to engage with people on another level.”

Part of the new policing approach helps officers better understand the personal lives of the people in their city. Of cities with more than 50,000 people, Camden ranks as the poorest in the country.

Part of the new policing approach helps officers better understand the personal lives of the people in their city. Of cities with more than 50,000 people, Camden ranks as the poorest in the country.

“If our officers are handing out $250 tickets, that can be life-altering,” says Thomson, who is the elected president of the Police Executive Research Forum, a Washington DC-based policing think tank. “We changed our internal performance metric system. We don’t judge an officer’s performance on the number of tickets they write or arrests they make. In fact, it’s the opposite. Our top five ticket-writers get investigated every month.”

The CCPD’s shift toward community policing has earned the department national recognition. During a visit to Camden in 2015, then-President Barack Obama held the CCPD up as a model for police departments around the country. Just last month, the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies dubbed the CCPD “the gold standard in public safety,” granting the force an accreditation held by just three percent of agencies in the state.

Trust in the police has grown thanks in part to policies designed to diffuse potentially violent situations and to truly help – not punish – people who are mentally ill. Officers are trained in de-escalation tactics that help them avoid ever having to use their service weapons.

Other guidelines have made a difference, too. The department has a “scoop and go” policy which instructs officers not to wait for an ambulance if a shooting victim’s life is in danger. Even in the event of an officer-involved shooting, they’re trained to load the injured person into their cruiser and head for the ER.

“We’re not waiting the minute or two for the ambulance to get there, because it could be the difference between life and death,” Thomson says. “Since we instituted this policy, every time an officer has used force on a suspect, we have been the ones to transport that person to the ER. In every one of these cases, the person has threatened to kill the police officer, but the moment that person is no longer a threat, the officers enter life-saving mode.”

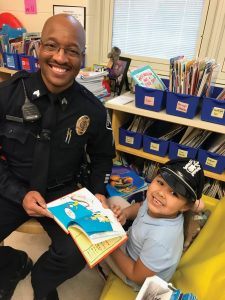

The department’s investment in Camden’s future also means building a relationship with its youngest residents. Officers hosts weekly “Movies With Metro” events and pop-up block parties throughout the summer. They also visit schools as part of a reading program called Bookmates and the Gang Resistance and Education Training (GREAT) program. Another program, Project Guardian, helps young offenders toward a better path.

Officers visit the homes of kids who’ve been picked up for petty crimes like truancy or who’ve started to head toward drug-dealing activity, and invite them to Project Guardian day. The adolescents and teens hear presentations, complete service projects, team up with officers for games and build personal relationships.

When the program began in 2014, a third of the city’s violent crime involved juveniles.

“We needed to intervene in these kids’ lives,” Assistant Chief Joseph Wysocki says. “At first we’d send a detective out with this invitation to 150 kids. About 50 people would shut the door on you, another 50 would say, ‘You’ve got the wrong kid,’ 50 would say they’d come and maybe a dozen would show up.” Now, he says, the program has close to 50 kids at each event.

“More than 30 percent of our population is under the age of 18,” Thomson says. “We’re trying to go upstream and prevent problems from occurring in the first place. That lies with the future of the city, which is the youth.”

After some time away from the city, Moulier bought a house in East Camden two years ago. He’s raising a 3-year-old daughter in a neighborhood he says is safer than it’s ever been.

“When I was younger and you called the police, it took a while,” he says. “My neighbors who’ve lived here for 20 years said they never got an officer to come out for anything. I’ve called recently, for non-emergency parking issues, and they’re there in five minutes. They’re making a sincere effort to adapt to the community. A lot of the officers are known in the neighborhood on a first-name basis. It’s not a publicity stunt. They’re working for the benefit and the uplifting of Camden.”