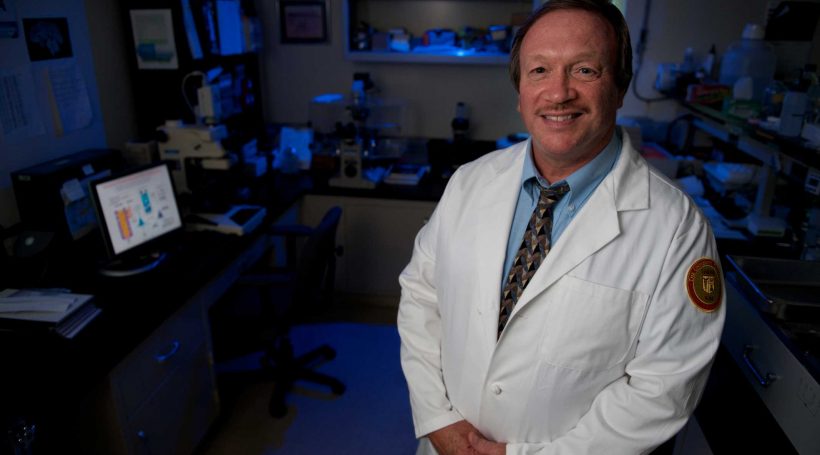

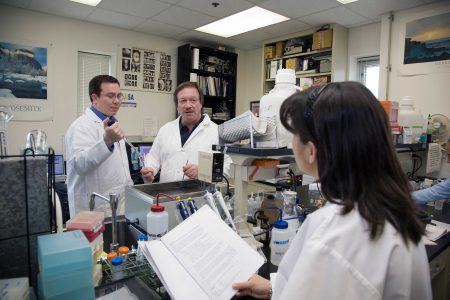

Medical research takes on new meaning when the disease you are trying to cure has ripped through your family. Scientist Robert Nagele, PhD, spends his professional life trying to understand Alzheimer’s disease. In his personal life, Nagele’s mother-in-law is battling the life-changing condition. And, his grandmother and two uncles were all diagnosed toward the end of their lives. “It’s a constant reminder I should be working as hard as I can,” Nagele says. And he is.

Nagele, 56, a professor at the NJ Institute for Successful Aging at UMDNJ-SOM, spoke with us about his work, and his hopes for a cure for Alzheimer’s.

Can you explain what Alzheimer’s disease is, and how it affects people?

Alzheimer’s disease is a very devastating neurodegenerative disease that is most associated with memory loss. It also takes away a person’s ability to think clearly or to learn, because neurons in the brain are no longer able to talk to each other, which is required for higher thinking and remembering.

How does Alzheimer’s disease cause memory loss?

People have something called a blood-brain barrier which is very important. It’s intact in people when they’re healthy, and its purpose is to keep things in the blood. When blood vessels travel through the brain, they make sure nothing leaks into the brain. As we get older, we experience aging-associated changes in our blood vessels, including the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. You begin to spring leaks in your brain, and they wreak havoc on the ability of the brain to function. There’s a material called amyloid that characteristically accumulates in the brains of people who have Alzheimer’s disease. You have it all over your body but not in your brain. When your blood-brain barrier breaks down, the deal’s off, the gates open and the amyloid begins to flood into the brain. The accumulation of amyloid is one of the hallmark characteristics of the disease.

How many Americans are affected by the disease?

At the age of 65, the incidence is four percent. At the age of 85, it’s 50 percent. I believe everybody has Alzheimer’s disease, it’s just a question of degree. The people who come to doctors’ offices just have more disease than we do.

You and your team have discovered a potential breakthrough. Can you talk about your work?

You and your team have discovered a potential breakthrough. Can you talk about your work?

We’re pretty excited about the recent discovery that we have antibodies in our blood with the capability of binding to nerve cells in the brain, if given the opportunity. If we get old and our blood vessels start to have problems, those antibodies can also leak out with the amyloid into the brain. The antibodies will bind to the nerve cells in your brain, and those cells don’t like that. The nerve cells want to wash their surfaces clean, and the way they do that, unfortunately for us, is they actually suck in. They pull the antibodies and amyloid inside and try to digest it. That’s where the problem starts. The amyloid begins to accumulate in your brain cells until the cell becomes bloated and eventually dies.

How can scientists use the new information you’ve discovered?

Our work suggests that there are three main things to be concerned about when trying to fight Alzheimer’s disease. First, is whether or not you have autoantibodies in your blood that can potentially bind to neurons in the brain. If they are present in your blood, it will be important to find out exactly which autoantibodies you have and how much of each. The second is the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. We would predict that a risky autoantibody profile would be of no consequence as long as the blood-brain barrier remains intact. This emphasizes the need for scientists to figure out exactly how the blood-brain barrier works, so that the drug discovery efforts of pharmaceutical companies can be aimed at finding new ways to maintain its integrity or repair it when it becomes leaky. Finally, a number of pharmaceutical companies are working very hard to reduce amyloid levels in the blood. This tactic will certainly help and probably postpone the time of disease onset as well as slow down disease progression.

What do your findings mean for patients with the disease, or those yet to be diagnosed?

A few things. Thus far, research work on Alzheimer’s disease has not yet led to the development of therapies that can slow or stop disease progression. All that is available are a few drugs, like Aricept®, that can mask the symptoms for a short while, but these drugs have no affect on the progression of the disease. New therapies require new ideas. For patients currently suffering from the disease, as well as those yet to be diagnosed, I would encourage them to do all they can to maintain their vascular health (and presumably the integrity of the blood-brain barrier). The specific recommendations are the same as those that are known to maintain good heart health. We will probably have to wait a few more years for drugs that can help maintain blood-brain barrier integrity and reduce risky autoantibody and amyloid levels in the blood. But the good news is I really believe that this is the approach with the most promise.

Is Alzheimer’s Disease hereditary?

There is a form of Alzheimer’s Disease that is inherited, but it is a mutation that is passed on from one generation to the next and it only accounts for four percent of the total Alzheimer’s patients. Ninety-six percent are considered to be sporadic. But it does run in families. It ran in my mother’s family. There were six children in her family and of the six, two of them died of Alzheimer’s disease and another one had dementia, which was leaning toward Alzheimer’s disease.

Was your family history the reason you chose this line of work?

Initially no. The reason I got into Alzheimer’s disease research was because I had a former PhD student who was working at Johnson & Johnson who called me and asked if I could use my special microscope system to take some pictures for his presentation. I was working on something related to cancer at the time. I had never seen Alzheimer’s disease before, but he sent me tissue samples and I was able to see a number of things that his team at Johnson & Johnson hadn’t noticed. He asked me to come out and give them a talk on what I saw, and I haven’t been able to get out of it yet. My mother is also very happy I’m working on Alzheimer’s disease. She says she has faith in me that I can fix this problem so I’m under a lot of pressure here! Every time I see her, she’ll ask, ‘So what are you finding?”

What is most rewarding about your work?

A lot of people go into research, like me. We work really hard and it’s really a great pleasure to do this. When I was around 11 years old, my dad told me that when I got older and got a job, I should make sure the job is something I love to do, something I would do for free. This isn’t a job to me. Every day I get to solve problems and puzzles that are important to everyone. You can help a lot of people if you discover something that is important.

What is your prediction for the future of Alzheimer’s disease?

I am very hopeful that it will soon be possible to slow or stop this disease. Accomplishing this will require a fresh approach, and we hope our work will provide this fresh approach. Once the field realizes the potential, the momentum will build and the rate of discovery will accelerate. Coming up with therapeutic strategies that can delay the onset of the disease or slow disease progression will have a tremendous impact on the otherwise grim statistics that make up the current forecast for Alzheimer’s disease. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to get this under control?

You and your team have discovered a potential breakthrough. Can you talk about your work?

You and your team have discovered a potential breakthrough. Can you talk about your work?