Photos: New Jersey Maritime Museum

Walk along your favorite South Jersey beach, and you might be closer to the remnants of a shipwreck than you realize.

Navigation errors, lousy weather, confrontations with other boats and war have led to the sinking of thousands of formerly seafaring vessels – and countless deaths – along the Garden State’s 130-mile shoreline.

Navigation errors, lousy weather, confrontations with other boats and war have led to the sinking of thousands of formerly seafaring vessels – and countless deaths – along the Garden State’s 130-mile shoreline.

While not every shipwreck’s story is known, the documented ones, spanning over 400 years, are meticulously kept and available through the free New Jersey Shipwreck Database. Compiled by the New Jersey Maritime Museum in Beach Haven, this free resource encompasses nearly everything known about the fates of Revolutionary War schooners, sunken submarines, fishing boat calamities and others. The database covers the obscure to the infamous. One such mystery is the SS Morro Castle, an American ocean liner whose 137 passengers and crew perished when it mysteriously caught fire on a return trip from Cuba, ultimately running aground with its burning hull in the shallow waters off Asbury Park.

“We have information on over 4,800 documented shipwrecks and disasters off the New Jersey coast – and who knows how many more are undocumented,” says Jim Vogel, the museum’s executive director.

“We have information on over 4,800 documented shipwrecks and disasters off the New Jersey coast – and who knows how many more are undocumented,” says Jim Vogel, the museum’s executive director.

The database focuses on maritime events along the waters of the New Jersey coast, primarily the Atlantic Ocean, Delaware Bay and Delaware River. Information is culled from newspaper archives, ship logs, diaries, official government documents, shipwreck books, periodicals as well as artifacts brought in by local divers.

“All available records, previously organized alphabetically, are now categorized in about 25 different ways, searchable by date, location and type of cargo,” Vogel says. “We’ve scanned every piece of paper. It’s a massive ongoing project.”

But the museum is much more than just a repository of digital records. It houses a boatload of treasures, artifacts and curiosities – including shipwreck relics, prehistoric fossils, navigation equipment and diving gear. There is a large storyboard of the 1916 Shark attacks that many people feel inspired the book and movie “Jaws,” including the clippings from the paper and pictures of the cemetery where the victims were buried.

But the museum is much more than just a repository of digital records. It houses a boatload of treasures, artifacts and curiosities – including shipwreck relics, prehistoric fossils, navigation equipment and diving gear. There is a large storyboard of the 1916 Shark attacks that many people feel inspired the book and movie “Jaws,” including the clippings from the paper and pictures of the cemetery where the victims were buried.

“And we’re about the only thing on Long Beach Island that’s free,” Vogel adds.

What attracts people to the musuem really varies, says Deborah Whitcraft, museum founder, president and treasurer.

“Some are fascinated by the Morro Castle because of the tremendous loss. Others gravitate to the personal remains from the crew of the S-5 submarine (a United States Navy submarine that sank in 1920 during a test dive off the coast of Delaware.). We also have swords, flintlock guns and ancient coins from shipwrecks dating back to the 1600s.”

“Each shipwreck has a unique story,” she adds. “We want to ensure they are not forgotten.”

Tracking shipwrecks is not just about preserving history. It has practical implications as well.

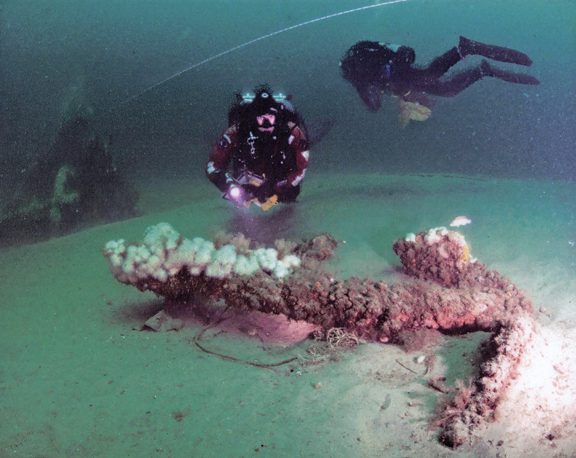

“Understanding where these wrecks are located helps in navigation and marine conservation,” says Vogel. Some shipwrecks have become artificial reefs, providing habitats for marine life. Others need to be identified as potential hazards to shipping lanes while others offer insights into the technologies and innovations in ship building and maritime industries.

New Jersey’s coastline, with its numerous shoals and treacherous waters, has seen more shipwrecks than any other part of the Eastern Seaboard, Vogel adds.

When the museum opened in Beach Haven on July 3, 2007, nearly all its holdings were the results of Whitcraft’s personal collection. A diver since her teens, she owned and operated a diving business, lectured, wrote columns on maritime subjects and served several terms as mayor of Beach Haven.

Whitcraft’s specialty was identifying the wrecks and researching their stories. Over the years, her collection grew, and when she ran out of space, friends stepped in to help store her finds.

“Back in the day, we knew there were wrecks, but not the names of the ships and details about them,” says Vogel. “The captains who found them might, for example, call them ‘Glory’ after their girlfriends. Years of research have gone into identifying and cataloging them.”

A turning point for the museum came in 1983 when iconic Philadelphia news anchor Jim O’Brien featured Whitcraft on a “Primetime” report on wreck diving. She spoke to O’Brien wistfully about opening a museum dedicated to New Jersey’s maritime history.

More than two decades later, in 2007, that dream became a reality. “We built the museum on our own land, using our own funds,” says Vogel, who married Whitcraft 27 years ago and adopted the obsession. “We formed a nonprofit corporation. Nobody gets paid here. We’re all volunteers.”

More than two decades later, in 2007, that dream became a reality. “We built the museum on our own land, using our own funds,” says Vogel, who married Whitcraft 27 years ago and adopted the obsession. “We formed a nonprofit corporation. Nobody gets paid here. We’re all volunteers.”

Their romance is of a seafaring nature. “I was a fisherman, starting as a mate on a charter fishing boat and was then a captain of commercial fishing boats for many years,” he says. “The museum is truly a labor of love.”

Divers’ finds encompass a large source of the museum’s collection and the diving community is also the beneficiary of the database. And, the database is a treasure trove for maritime researchers. “We’ve had students do their master’s thesis using it, young people working on science projects, and even a group that participated in a nationwide science fair,” Vogel says.

Visitors often arrive with little understanding of New Jersey wrecks but leave with a newfound appreciation, he adds.

“Many come in asking about the Titanic and may be disappointed at first,” says Vogel. “But the Titanic was straightforward: an iceberg sank it, and many people died. The Morro Castle is a much better story.”

The vessel, which made regular voyages from New York to Havana, Cuba, mysteriously caught fire about 12 miles off Barnegat Light during its 171st voyage in September 1934. The burning ship eventually ran aground in front of Convention Hall in Asbury Park, resulting in the loss of 137 lives.

The museum devotes an entire room to the Morro Castle, with rare photographs, original 1934 video news footage of the disaster and an authenticated life vest worn by one of the survivors.

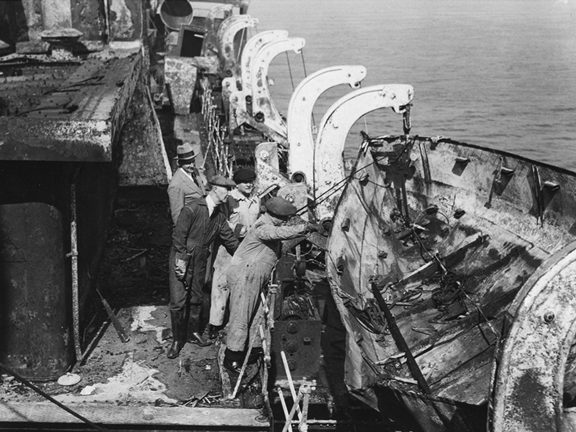

Another notable collection is that of the USS Robert J. Walker, an iron-hulled, side-wheel steamer assigned to the United States Coast Survey (the forerunner of the Coast Guard) to chart the coast. The Walker sank on June 21, 1860, after a collision with the schooner Fanny near Atlantic City, about 12 miles off Absecon Inlet. The museum houses the only permanent exhibit of the Walker.

Another notable collection is that of the USS Robert J. Walker, an iron-hulled, side-wheel steamer assigned to the United States Coast Survey (the forerunner of the Coast Guard) to chart the coast. The Walker sank on June 21, 1860, after a collision with the schooner Fanny near Atlantic City, about 12 miles off Absecon Inlet. The museum houses the only permanent exhibit of the Walker.

People often inquire about the museum’s collection of recovered gold coins, hoping for treasures from pirate ships or otherwise. “There’s not a lot of gold here in New Jersey,” Vogel explains, “While there are rumors of a few wrecks containing gold, very little has actually surfaced.”

Besides, he says, all that glitters isn’t the only undersea treasure.

“Divers are an odd assortment of people, with some interested in lobsters, others in brass portholes, and some looking for china (not the country),” he says. “Different people have different ideas of shipwreck treasure.”

Buried Treasures

Although erosion and the sands of time have obscured the views of most shipwrecks, some are still visible along the South Jersey coastline, offering glimpses into the region’s rich maritime past:

SS Atlantus: One of the most famous visible shipwrecks, the SS Atlantus is a concrete ship partially submerged off the coast of Cape May at Sunset Beach. Built during World War I, the Atlantus was later used for various purposes before running aground in 1926.

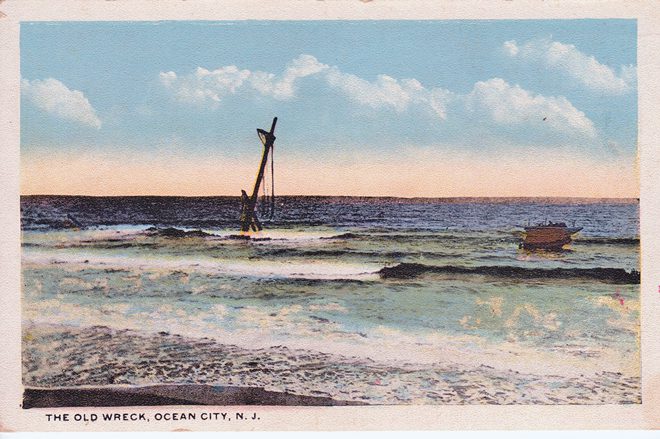

The Sindia: Off the coast of Ocean City, the Sindia was a four-masted ship that ran aground in 1901. While much of the wreck is buried under sand, remnants occasionally emerge and can sometimes be seen during certain weather conditions.