WWII U.S. Army Medic Tim Kiniry and Concentration Camp Survivor Steven Fenves met for the first time on Zoom

It’s been 77 years since Andrew “Tim” Kiniry entered the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, stunned and horrified by what his eyes were seeing. There are images that haunt him to this day.

“Not only the sights, the odor, oh my God, it was terrible,” says Kiniry, 101, of Buena. “You look at these people and wonder, are they human? It was like they were clothes hanging on bones covered with skin. We spent the afternoon there, seeing the crematoriums, the ovens, the ashes, the ditches, the whipping posts, all the things the Nazis used for their cruelty. It was brutal.”

Nothing – not Kiniry’s training as a U.S. Army medic or his prior experiences helping the wounded in bloody World War II battlefronts – could have prepared the 24-year-old soldier for what he witnessed, he says. With so few still alive to remember that moment, Kiniry considers himself lucky that he was able to meet Steven Fenves last summer to gain another perspective of that fateful day. Fenves, 91, was a prisoner at Buchenwald when U.S. soldiers – including Kiniry – showed up to liberate the camp.

The emotional meeting was arranged through the Millville Army Air Field Museum and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. Portions of the conversation can be viewed on the Air Field Museum’s website.

Fenves, who came from an affluent family in what was formerly Yugoslavia, was just about 10 when Germany attacked and upended his former life. His father Lajos, editor of the largest daily newspaper in Hungary, was taken to Auschwitz, a concentration camp in Poland, while the rest of the family was forced to leave their home and resettle in a ghetto. Fenves was just about to turn 13 when the rest of the family was deported to Auschwitz. Separated from his family, he managed to survive by volunteering to be an interpreter for his captives. He was eventually taken to another camp where he worked building German aircrafts. There, he became part of the resistance.

“It was a very small camp of about 700 inmates,” Fenves told Kiniry. “Our camp orderly was a German political prisoner who was an active member of the [resistance]…He had a pretty good idea of what the resistance organization intended to do to liberate the camp before the Americans arrived. There were 6 of us who were really just kids. We had grandiose plans, how we were going to participate.”

But it was not to be. On the night of April 1, 1945, the Nazis forced all prisoners onto a grueling Death March to Buchenwald. It lasted about 10 days. Out of 700, only 300 inmates survived.

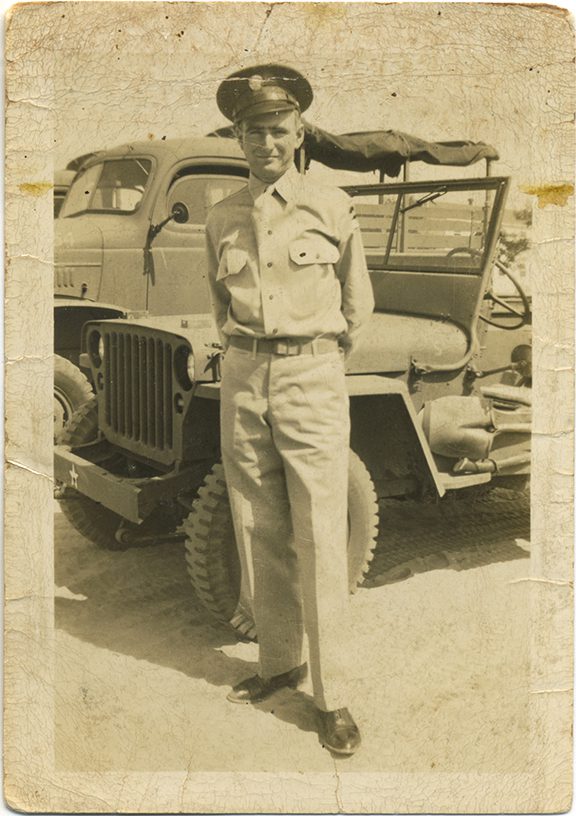

WWII U.S. Army Medic Tim Kiniry

“On the way, we actually heard the noise of the war,” Fenves told Kiniry. “When we got to the camp, I was so sick and tired that I fell into the first bunk and fell asleep. I had no food, nothing. I woke the next morning to the excited screams of my buddies, who told me I slept through the whole thing. We went out to the electrified fence. The power was off, and we watched the Americans go by. There was elation everywhere. People you thought would never again stand upright were rising from their straw cots and started running up the steep hill towards the Americans, cheering, waving.”

After liberating the camp, Kiniry was stationed as a medic in a different hospital than the one Fenves was taken too. Although they likely did not cross paths at Buchenwald, both said they were grateful to connect 7 decades later by Zoom.

At 101 years old, Kiniry is the picture of vitality, with a broad smile and a clear, strong voice. A retired machinist, he still drives and helps out part-time at a friend’s towing service. He also volunteers for the Air Field Museum, telling his war stories to local students. Last year, when he mentioned to museum personel that he’d like to meet a Buchenwald survivor, it set the virtual encounter in motion.

Kiniry took the call at the museum, which is where P-47 Thunderbolt pilots trained before heading to Europe to fly missions against the Nazis. Fenves dialed in from his home in Chevy Chase, Md. Kiniry recounted the difficult tasks he and his unit had to undertake, including processing 600 survivors who were critically ill with tuberculosis.

“The first thing we did was burn their clothes,” he told Fenves. “Then we tried to give them showers. It was tough because the only thing they could think of was being gassed, but after some did it, more followed. Then we sprayed them with DDT, which at the time was the approved treatment. We did X-rays. We set them up in a ward with pillowcases and sheets, which was a luxury for them.”

Nurturing emaciated survivors back to health was difficult because they could not tolerate food. “We started giving them chocolate milk, malted milk, eggnog and candy to build them up little by little,” Kiniry said. “Our mess hall finally came up with a high-calorie diet.”

Fenves, who had never had the chance to thank his liberators until now, listened intently. “I’m eternally grateful to them, what they did, the battles they fought to get to us, the care and sustenance they provided afterwards,” he said. “I would not be here if that help had not arrived.”