It’s hard to believe, but here in New Jersey children as young as 13 can legally marry. And they do. Nearly 3,500 children were wed in New Jersey between 1995 and 2012.

Many times, it is an arranged marriage of a young girl to an older man. But every time, it is with parental consent.

Throughout the United States, thousands of teens and pre-teens are forced into marriage. And no law can protect them.

The issue seems unfathomable. In the United States, the minimum age to marry in most states is 18. That’s the age, as per federal law, in which there are no restrictions for consensual sexual relations. However, every state has exceptions.

In New Jersey, there are two loopholes: teens can wed with parental consent at 16 and 17, while children 15 or younger are permitted to enter marriage with judicial approval. The Garden State is one of 27 that carries no minimum age to marry.

Lawmakers, however, are trying to change things. Connecticut, Maryland, Missouri and Texas have introduced legislation to close loopholes allowing for the marriage of minors through parental or judicial consent. Earlier this year, the New Jersey legislature passed a bill that will ban marriage for those under the age of 18 without exception – the first state law of its kind. The bill currently awaits Gov. Chris Christie’s signature.

Still, it is not without its critics. Although the bill sailed through the state Assembly with a 64-0 vote and seven abstentions, the Senate approved its version of the law 26-5. Senator Michael Doherty (R-23), a dissenter, feared that a “one size fits all” law would lead to more abortions. He also argued that couples with one partner in the military should still be permitted to marry before 18.

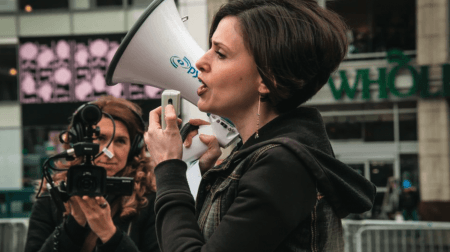

The spur of government action was sparked by an op-ed article by Fraidy Reiss published in “The New York Times” in October 2015. Reiss is the founder of Unchained At Last, a New Jersey nonprofit working for marriage reform. She grew up in New York, and was married at age 19 to a man she had known for three months. Her parents arranged the marriage.

“Marriage was something I looked forward to,” Reiss says. “My goal was to marry young and have children.”

Unchained At Last founder Fraidy Reiss; Photo by Susan Landman

“In the [Orthodox Jewish] community, it’s shameful for someone to turn 20 and not be married yet. Everyone I knew was in an arranged marriage. It never occurred to me that this could be a bad thing. One week after our wedding, he woke up late and was mad at himself for being late. He started screaming and cursing. He punched his fist through the wall and left a big hole in the sheet rock. That was when I knew I was in a bad situation.”

Reiss remained married for 12 years, and the abuse continued.

“He would break things – dishes, windows, furniture, cabinet doors – and during this he would describe to me how he was going to kill me,” she says.

“He’d say things like, ‘I’m going to wrap my hands around your neck and squeeze until you can’t breathe anymore.’ But he’d never actually touch me. He’d do things to scare me. If we were driving, he’d speed up to 100 miles per hour and then slam on the brakes. He would say terrible things to our daughters. He was always convinced I was cheating on him, and he’d tell them, ‘Your mother’s a whore. She’s cheating, and I’m going to kill her.’ When he got really upset, he’d say he was going to kill them, too. I went to my family, his family, the rabbi; they’d say, ‘He’s not hitting you. You’re overreacting.’”

Reiss’ story is not uncommon. In the United States, nearly 248,000 children – almost all of them girls, some as young as 12 – were married in the United States between 2000 and 2010. A large majority of the girls married men many years their senior, while some were wed at an age, or with a spousal age difference, that constitutes statutory rape under their state’s laws.

Assemblywoman Pamela Lampitt (D-6), who co-sponsored the New Jersey bill hopes new legislation will eliminate child marriages.

“…We are protecting the human rights of these girls, ensuring that these children are not exposed to the violence and dangers that can accompany these forced marriages,” says Lampitt.

Although most states do not provide identifying details about brides and grooms, child marriages occur in nearly every American culture and religion. Rutgers-Camden law professor Sally Goldfarb says it’s important to consider why children would be encouraged or pushed into marriage.

“The issues seem to revolve around cultural practices as well as opposition to sex outside of marriage,” says Goldfarb, who teaches family law. “The question is whether those considerations should outweigh the societal value of young people reaching the age of majority – 18 – before they make a serious, legally binding commitment.”

The rationale for parental exemptions, she explains, is that mothers and fathers are supposed to be looking out for their children’s best interest. However, that’s not always the case.

“Parents’ assumptions about what is good for children often reflect their own background and priorities,” Goldfarb says. “They may be more concerned about their own social or economic standing or advancing values of their own cultural or religious community than the actual well-being of their own child.”

Reiss says that growing up in an abusive household contributed to the doubts she had about her own abuse.

“My father was extremely violent, and my mother didn’t leave for many years, because her parents refused to take her in. When I was 27, a friend of mine said she was secretly seeing a therapist from outside the community. She recommended that I go see this therapist,” Reiss says.

“It was the first time in my life that someone actually said, ‘This is domestic violence. You are not safe. You have to leave.’ That therapist also explained to me that I had legal rights.”

It took multiple attempts – including two restraining orders – before Reiss was able to escape and receive a legal divorce. In 2011, she says she came to the realization that she needed to work freeing other “chained” women.

“I started recruiting people to join the effort. I was very aware that what was happening to me was happening to women in communities here in the United States and across the world,” she says.

In the five years since Unchained At Last was granted nonprofit status, Reiss and a team of more than 400 volunteers have helped more than 270 women and girls escape forced marriages.

“The biggest problem is people don’t know this is happening in the United States,” Reiss says.

“They think arranged marriage is an adorable cultural process that results in a lower divorce rate. The first thing you have to do is put a name to it. This is a human rights violation.”

“Other countries are far ahead of us. In 2014, the United Kingdom criminalized forced marriage. Here, there are very few laws that can be used to punish anyone. Young women call us and say, ‘You have to help me; my family is planning to marry me off against my will in a month.’ And there’s no law that says they can’t.”

Kate Morgan contributed to this article.