When Vicky Hammer got a call from her granddaughter’s daycare center saying the 9-year-old hadn’t been picked up, Hammer had a bad feeling. She knew her daughter Misty Dawn would never forget to pick up Tiara. Something had to be terribly wrong.

“It was about 6:30, and the daycare was closing at 7,” recalls Hammer. “Misty used to pick up Tiara around 4:30. If she had gotten a flat or anything like that, she would call me or one of her brothers. She would never just not show up. I drove to get Tiara. I called my son Kelly and said something’s wrong and asked him to go over to Misty’s house. I thought maybe she got sick, or she and her ex-boyfriend were fighting and he wouldn’t let her out of the house. I was pretty nervous and knew something was wrong, but you just don’t allow yourself to think the worst.”

“My brother Jason and I pulled up in the parking lot,” adds Kelly Ramos, who goes by the nickname Kell. “Her car was there. We looked in the window, and the blinds were all messed up. I had the feeling somebody was fighting and ran into them. The door was unlocked, and she always locked the door. We walked in, and she was lying on the floor. Her shirt was halfway off and she had some blood under her nose and red, strangulation marks around her neck.

“All her possessions from her pocketbook were spread out like she was grabbed. We checked, and there was no pulse. She was cold and solid, so we knew she was dead. We put a blanket over her and called the cops.”

The boys then had to call their mother.

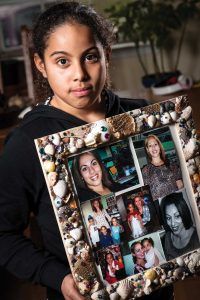

Tiara was 9 years old when her mother, Misty Dawn, was murdered in 2011

“He called me and said, ‘It’s not good,’” says Hammer. “I said, “What do you mean?” He said, ‘It’s not good.’ I couldn’t get it through my head. He said, ‘She’s gone.’ I broke down, but Tiara was here and she started screaming, ‘What happened? Is she dead? My mommy!’ I couldn’t answer her. How do you tell a 9-year-old kid? They were two peas in a pod.”

Misty was just 31 years old on that tragic day, November 7, 2011. Misty and her mother were close. In fact, she and Tiara lived with Hammer in her Bordentown home for the first six years of Tiara’s life.

“Misty worked with children for most of her life as a preschool teacher,” says Hammer. “The kids and parents all loved her. Her personality was very alive. She was also studying to be a massage therapist when this happened. But she was very hardheaded. When she wanted to do something, she’d do it. She just kept thinking she could get through to this guy.”

The guy was Noel Irizarry, who had only dated Misty for six months before that fateful day. He pleaded guilty to her murder and was sentenced to 30 years in prison. What Misty didn’t know was that Irizarry had a history of domestic violence and had previously served more than nine years in prison for attempting to kill Fatima De Pierola.

“I started going out with him when I was 15 and was with him for six years on and off,” says DePierola. “In 1994, when I turned 21, I broke up with him because he was so controlling. He said if I broke up with him he’d cut my throat, but I never took him seriously. Two days later he was waiting for me inside my house. I came home with my daughter, Sofia, who was 3 years old at the time. He was standing there with a bat. I grabbed my daughter and ran into the bathroom, but he kicked the door open and started swinging the bat and calling me names.

“We ran into the living room, and my daughter was hanging on my leg yelling for him to stop hitting mommy. He started swinging at her. I blocked the bat with my hands, and he broke a few of my fingers. I was in such shock I didn’t feel the pain until afterwards. I begged my daughter to go into a bedroom. He beat me with maybe 40 blows to the head. He also cut my neck open with a box cutter. I must have blacked out and when I got up, I begged him to let me call an ambulance.”

Irizarry agreed on the condition that she would pretend an intruder had beaten her. He threatened that if she told the truth, he’d come back and kill her. But DePierola did tell the truth. Irizarry was sentenced to 30 years in prison, but he was paroled after just nine-and-a-half.

“We wouldn’t be talking about this if Misty had known that,” says Hammer. “What she knew was that Irizarry was lying to her about a lot of things. He promised her the world, and she bought it all. He said he had this really good job, and he was buying her this house. Little by little things were not panning out. She was too trusting. He would cry, and that just broke her heart. She thought she could help him.”

“She even tried to look him up in a state database, but he had lied about his age so it came back with a clean record,” adds Ramos, whose mission now is to create a domestic violence registry where previous offenders would be unable to hide.

Assemblyman Reed Gusciora from Trenton’s 15th district is spearheading a bill to establish a publicly accessible domestic violence Internet registry.

“We have a register for sex offenders under Megan’s law,” says Gusciora. “This would expand that to include those who are convicted of aggravated assault, and that includes domestic violence. Too many domestic violence convictions go unnoticed, particularly by family members or potential dates. This would give an open public record to those who are convicted. It’s for those who commit the most egregious crimes against their domestic partner.”

Gusciora believes that in the age of online dating, this bill is especially important. “People go on dates with anonymous partners, and this would be a way to check that,” he says. “And in cases where a battered spouse has a hard time breaking away, family members could provide a greater support network if they knew who their child was going out with.”

The bill is currently in committee, and Gusciora is hopeful it will pass. “There’s a learning curve to educate other members, and there may be similar situations to Kell’s in other districts,” he says. “It’s a matter of finding those legislators who will help push it through.”

For Kell Ramos, there was a time in his life when he might have been included in that database. He is forthright about his own struggles with domestic violence and is currently trying to patch up his relationship with his wife, who he admits, he abused for a long time.

Kelly Ramos and his wife Tamara have experienced domestic abuse both in their childhood homes and in the home they have made with each other

“The house that Misty and I grew up in was like a war zone,” he says. “Everybody was fighting all the time. My stepfather would ignore us for months – walk by and not even acknowledge you. Then he’d break out of that spell and scream at us for whatever stupid reason.

I walked around on eggshells and it did damage, emotionally and mentally. I carried those ways into my relationships with girls. I had to dominate the girls.

“My wife, Tamara, also came from a very abusive home. It was passed down from generation to generation. Her grandfather killed her grandmother in front of all her kids. He beat her and strangled her to death. Her father was an alcoholic who beat her mom. I would belittle her, talk down to her, and I hit her a few times.

I would treat her the way my stepdad treated us. I was emotionally disturbed and had a lot of emotional pain.”

The couple had two children, a boy and a girl, who are now 15 and 13. Addicted to drugs and alcohol, Ramos joined AA and started to clean up his act in July 2002.

“I had these two little kids and that was the motivation for me to get sober,” he says. “You do a lot of soul searching in AA, and you listen to what people tell you about yourself. That’s what started my change.”

His real epiphany came after seeing a baby picture of his wife. “That little girl became my wife, and my daughter was about that same age,” he recalls. “How would I like somebody treating my daughter the way I was treating my wife? That was the biggest change for me. I would never hit my wife or any woman again.”

Now sober for more than 11 years, Ramos is determined to end the vicious cycle of domestic abuse. He is using his skills and contacts as a videographer to create a documentary called “Misty Dawn” to highlight the problem.

“My main goal with this documentary is to show that violence against women is a man’s problem,” says Ramos. “We have to change the mindset among men. If a child gets abused, the whole community and society is outraged. We want justice. But if a woman is abused, people don’t care as much. We need to make that more of an issue. First and foremost, men have to stand up and say this is not ok. We have to stop it from a young age.”

Ramos is funding the documentary through grants and private donations, and hopes to complete it by the end of the summer. He is exploring his options for distribution but hopes his message reaches a wide audience.

“I am not going to let this happen to my daughter,” Ramos says, “and I’m going to do everything I can to make sure of that.”