PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAVID MICHAEL HOWARTH

Jadyn Brown, 16, has spent more than half of her high school experience at home staring at teachers through a computer screen. And as much as she’s grateful that school is back in person this year, it’s still far from normal.

“Right now we have a schedule where we are not in lunch because of the Covid cases,” says Jadyn, a junior at Eastern High School in Voorhees. “So I miss the idea of being around my friends and not having to be like, “Oh, what if this person has it?”

On top of that, she says it’s still a struggle to get up so early, make it to school on time and manage her demanding workload after so many sedentary months.

The pandemic-related decline in child and adolescent mental health has become a national emergency.

She’s far from the only kid still adjusting to in-person learning. School districts across South Jersey have made changes big and small to deal with a school population that’s far needier than in pre-pandemic days. The grief, anxiety and depression children have experienced during the pandemic is still affecting classrooms and hallways, resulting in more disruptive behavior, absenteeism and academic struggles. It’s so serious that last year, 3 major children’s health organizations – the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Children’s Hospital Association – declared that the pandemic-related decline in child and adolescent mental health has become a national emergency.

One of the biggest challenges for many students has been the return to a structured school week, says Kristin Borda, Eastern’s director of academic programs and student performance.

“This includes getting to school each day, navigating the increase in social interactions and managing time for homework and other activities beyond the school day,” says Borda. “For some, there can be a lot of anxiety related to the adjustment of relative isolation during the pandemic to returning to a building with over 2,000 students.”

Anticipating that, Borda says, Eastern’s Student Alliance – a peer mentorship program – took on a bigger role this school year. Jadyn, who is a peer mentor, was among students who underwent training over the summer through the Wingman Youth Leadership Program. Started by a parent whose son was killed in the 2012 Sandy Hook school massacre, Wingman trains students to run activities designed to help their peers feel more connected to school and their classmates. Once trained, the Student Alliance members then led workshops for first-year students during Eastern’s transition camp right before the start of the school year.

“I was able to participate in the activities, teach the freshmen and meet new people. It helped me establish a better mindset about going back to school,” says Jadyn, who led younger students in ice-breaker games and trust-building activities designed to emphasize compassion, empathy and inclusivity.

Throughout the school year, Jadyn and other Student Alliance members run Wingman programs during the school day. With the addition of a full-time mental-health provider, Eastern also provides more face-to-face counseling for students in need, Borda says. In addition to talking to students, the provider is teaching mindfulness skills through yoga and meditation. In addition, staff are quicker to reach out to students who are missing school. The school also expanded extracurricular options to encourage more student engagement, Borda says.

But it’s not just students in need of support. Eastern brought in an educational consultant this year to provide teachers with strategies for dealing with more demanding situations.

Other South Jersey schools have taken different approaches. At Moorestown Friends School, the transition was a little easier as most students attended in person in the 2020-21 school year. Still, it’s not business as usual because everyone is still processing the loss, social justice challenges and the toll of social separation, says Head of School Julia de la Torre. As she sees it, schools must be able to meet kids where they are, she says. And at this moment of the pandemic, restoring students’ sense of safety is paramount.

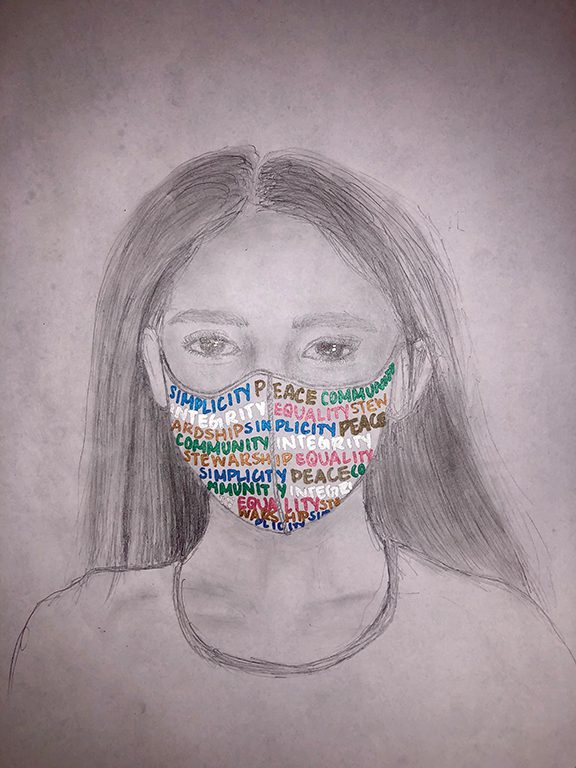

Sketch made by Christine Chandran, MFS Class of 2021, is part of “Friends Apart,” a Covid-19 archives project

Jadyn Brown, left, leads a Wingman activity at Eastern High School

“As a small Quaker institution, we have always relied on our close-knit community to see us through challenges,” says de la Torre. “We cherish opportunities to bring students together for traditions and shared experiences. We have prioritized them since it allows our teachers to spend quality time with students outside of the classroom setting and to solidify important peer-to-peer relationships.”

The school also provided a creative outlet for students, alumni and families to reflect on their experiences. This resulted in “Friends Apart,” the Covid-19 Archives Project, a collection of short essays, poems, art and photography all collected online from the youngest kids to teachers and alumni who graduated as far back as the ’60s.

The stories detail a time of great challenge, resilience and hope, says de la Torre. And now the archive, which is available online, is part of the school’s history.