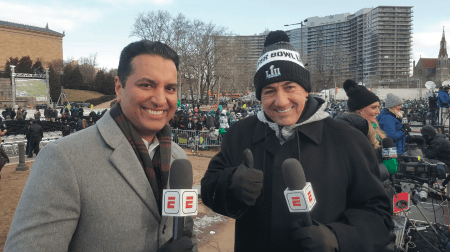

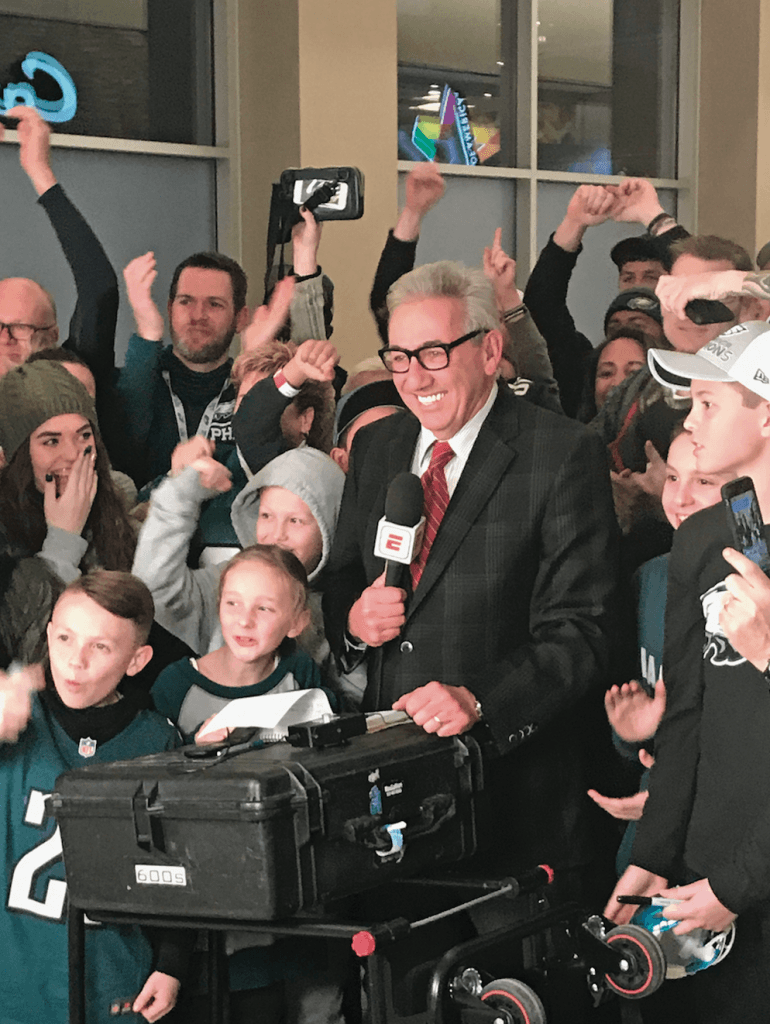

Photos by Brian Franey

The Eagles gave us a great season. But, beyond that, they gave us a great story.

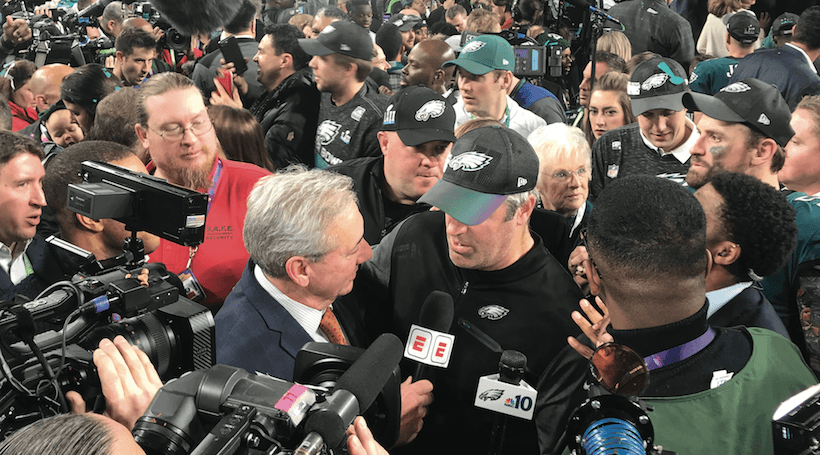

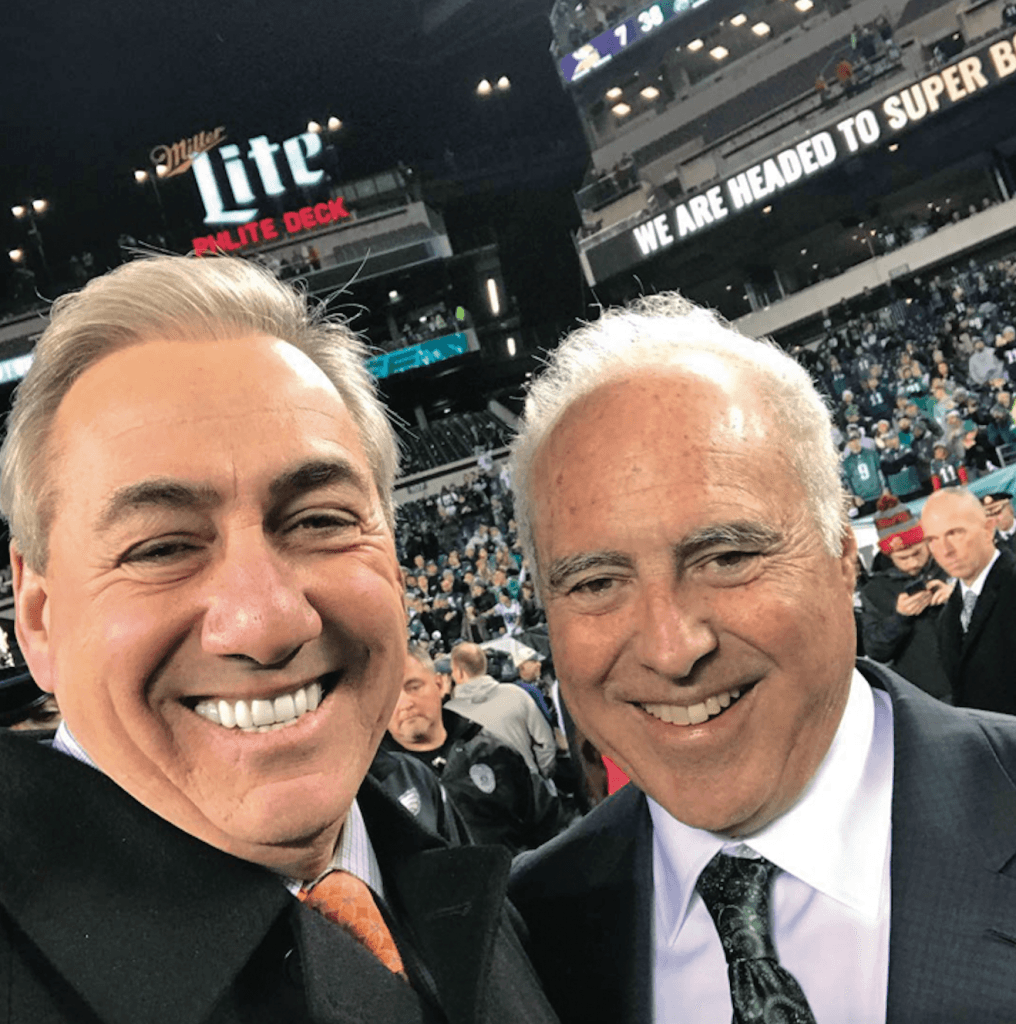

For me, the highlight of that story happened just minutes after Tom Brady’s hail mary pass to tight end Rob Gronkowski fell harmlessly to earth. Just after NFL commissioner Roger Goodell handed Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie the Lombardi Trophy – as green and white confetti cascaded onto the players and coaches and their families – Doug Pederson descended from the national television riser and met me at the bottom of the steps.

Here we were, two guys who live just a mile or so from each other in Moorestown, at the confluence of our careers and history, with hundreds of cameras and reporters from all over the world surrounding us, talking to one another about how the Eagles did it – beat the mighty New England Patriots and won their first Super Bowl title.

We looked at each other, the camera rolling. Then my instincts just took over. I knew I had just a few minutes before Pederson’s NFL escort was going to yank him away from me, so I dispensed with the pleasantries and just did my job: I asked him a simple question.

We looked at each other, the camera rolling. Then my instincts just took over. I knew I had just a few minutes before Pederson’s NFL escort was going to yank him away from me, so I dispensed with the pleasantries and just did my job: I asked him a simple question.

“Doug,” I said, “you said all along this would be a 60-minute game, it would come down to the end; how did you do it?”

“It’s just a resilient group, Sal,” he said. “They battled all year long. I just made my mind up to stay aggressive all the way throughout the game. Trust our players. Trust our quarterback. Trust our players to make plays.”

Let’s talk about those two things: Staying aggressive and trust.

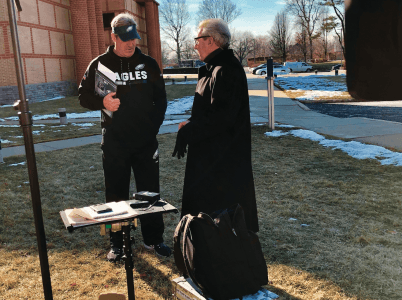

I remember talking with Pederson the morning of his first regular-season game, Sunday, Sept. 11, 2016. His father, Gordon, who was his mentor and taught him the game of football, had just passed away. In fact, Pederson had just returned from the funeral in Louisiana. So Pederson was about to take the field in his professional debut with a hole in his heart.

“Doug,” I said at the end of a short, three-question pre-game interview for ESPN’s Sunday morning show, NFL Countdown, “What advice do you think your dad would give you this morning?”

“He would say, ‘Son, be yourself, but stay aggressive. Always stay aggressive,’” Pederson replied.

Covering his tenure for two years, I always came back to that interview as a guidepost to understanding Pederson’s go-for-it mentality in year one as the Eagles head coach, an approach that was perfectly suited for his rookie quarterback, Carson Wentz, the young buck from North Dakota who took the franchise and the NFL by storm.

Pederson was often criticized in 2016 for going for it too often on fourth down. He was called misguided and foolhardy. But, in retrospect, he was setting the foundation that would allow him to remain aggressive throughout the championship season of 2017, including going two-for-two on fourth down in Super Bowl LII.

Pederson was often criticized in 2016 for going for it too often on fourth down. He was called misguided and foolhardy. But, in retrospect, he was setting the foundation that would allow him to remain aggressive throughout the championship season of 2017, including going two-for-two on fourth down in Super Bowl LII.

The night before Super Bowl Sunday, I was the only reporter invited into the Eagles team hotel, the Radisson Blu, on the south end of the Mall of America. Pederson and I met in the lobby for a long interview for SportsCenter. As a small gift of appreciation for his time and candor all year long, I brought him his favorite dessert: a pint of Haagen-Dazs vanilla ice cream. I asked him if he would be channeling his father Gordon on Super Bowl Sunday. “I’ll definitely be thinking about him,” he said. “I’ll be thinking about what he told me.”

Which brings us to the most famous and successful fourth-down play in Super Bowl history: The Philly Special.

Now, I want you to think about this for a minute. NFL coaches, by nature, are conservative. They rarely go for it on fourth down. But going for it on fourth down on the 1-yard line in the Super Bowl – running a play that’s never been tried in the 52-year history of the Super Bowl, a play that your team has never tried before in a game – that’s being aggressive. In the streets, in the locker room, they have another nickname for that brand of hutzpah, but this is SJ Magazine, so you can figure it out on your own.

And this play – a reverse toss to a tight end who throws a pass to the quarterback leaking out of the line of scrimmage into the end zone like a cat burglar who just snatched a plate of chocolate chip cookies on his way out of the house – starts with a direct snap to an undrafted rookie running back out of Glassboro High School!

Now, that’s a wow.

Now, that’s a wow.

So here are the particulars: 38 seconds left in the half, the Eagles had fourth-and-one. Even though the Patriots had just scored, Philadelphia had the lead, 15-12. So Pederson could’ve kicked a field goal, gone up 18-12 and nobody would have questioned him. But Pederson’s defense was failing him, and he knew it. They could not stop Tom Brady and would not stop him until late in the game, which Pederson had no way of knowing.

During a timeout, quarterback Nick Foles came to the sideline, looked at Pederson, who held the laminated play sheet over his mouth. Foles said, “Philly, Philly?” Pederson knew what he meant: Philly Special – a play that the Eagles had practiced for four weeks and were going to run against the Minnesota Vikings in the NFC Championship game – but decided the Vikings might sniff it out. This time, Pederson just said, “Yes, let’s do it.” That simple.

Foles went to the huddle and said just two words, “Philly Special.” At the line of scrimmage, he yelled, “Kill, kill!” and moved slightly to his right, behind right tackle Lane Johnson. Running back Corey Clement – from Glassboro High – took the direct snap, ran to his left and tossed the football like a loaf of bread to tight end Trey Burton, who was a high school quarterback in Florida.

Burton threw a perfect spiral to Foles, who played basketball in high school in Texas and with big hands has caught many passes in the low post.

“It seemed like the ball would never get there,” Foles told me. “All I kept telling myself was, ‘Focus on the ball.’ I knew I was already in the end zone and all alone.”

The touchdown shocked the world. Burton became the first tight end in NFL history to throw a touchdown pass in a Super Bowl. And Foles became the first quarterback to catch a touchdown pass in a Super Bowl. More important, the call and its execution announced to the Patriots they were in a fight, and it proclaimed to the Eagles players standing with Pederson that he entrusted them to win the most important game of any of their lives.

Particularly Foles. Remember, this is the guy who replaced a player who had reached mythical, Paul Bunyanesque status in just 29 NFL starts: Carson Wentz. Foles needed to know that Pederson trusted him – make no mistake about that. Since Dec. 10, when Wentz blew out his knee in Los Angeles, Pederson’s trust in Foles never publicly wavered – even while Foles’ game went through the natural ebb and flow of a late, in-season replacement quarterback.

Particularly Foles. Remember, this is the guy who replaced a player who had reached mythical, Paul Bunyanesque status in just 29 NFL starts: Carson Wentz. Foles needed to know that Pederson trusted him – make no mistake about that. Since Dec. 10, when Wentz blew out his knee in Los Angeles, Pederson’s trust in Foles never publicly wavered – even while Foles’ game went through the natural ebb and flow of a late, in-season replacement quarterback.

But by making that call, Pederson put a very public stamp of belief on No. 9 that clearly permeated throughout the whole team. “That play call said to all of us, ‘We got this – to the bitter end,’” safety Malcolm Jenkins said.

Foles, the MVP of Super Bowl LII, had done what many quarterbacks had tried to do for the Eagles franchise and its fan base: bring home the Lombardi Trophy.

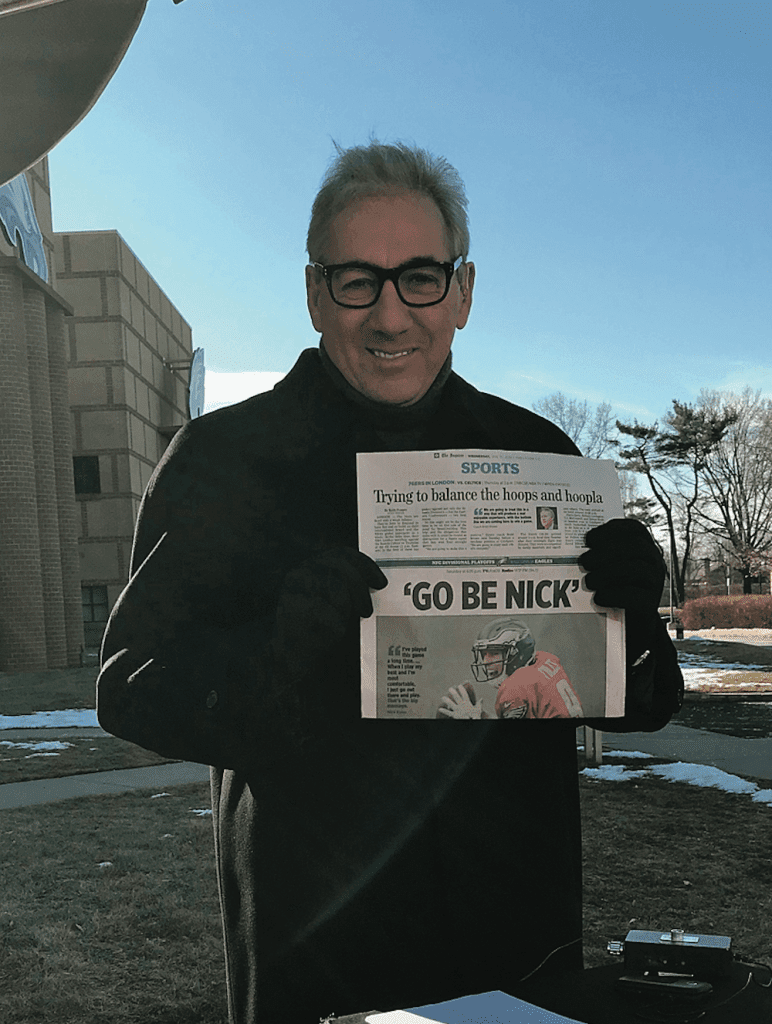

Four days after the game, the day before the biggest championship parade in the city’s history, I had a quiet moment with Foles outside the Eagles locker room at the team’s NovaCare practice facility in South Philly.

“Nick,” I said to him, “I hope you know what you’ve done. You’ve erased three generations of doubt and disappointment and disrespect – not only for this team and franchise, but for a community of people, millions of fans around this area and all over the country who have waited for this moment.”

He just looked at me, soaked it all in. I knew he got it.

He just looked at me, soaked it all in. I knew he got it.

I continued: “Just from my perspective, I’ve covered this team for 25 years – trying to tell the story of this quest. That’s a lot of road trips. A lot of Sundays away from my family. A lot of sacrifice my family made for me to be with this team. So for my family there is certainly elation and closure. You did it for all those families out there who I can tell you are feeling the same thing.”

He reached out and hugged me, and said, “That’s awesome.”

“Yes, it is,” I said. “Thank you.”

And then, literally 30 minutes later in an auditorium on the other side of the building, Pederson ruined that touchy-feely moment. Pederson proclaimed that the team was not done. The story was not over – that we were all not going anywhere.

“Get used to this,” Pederson said. “Get used to playing football in February. This is the new norm. This is just the beginning.”

Sal Paolantonio, a national correspondent for ESPN, has covered the NFL for 25 years. Follow him on Instagram.