Like many people, Michael Gomez’s life changed on 9/11. On that fateful day, he was teaching at an all-boys Jesuit high school in Jersey City – a school with a clear view of the World Trade Center.

“I was going to stay there forever, because I was able to teach my favorite books, coach baseball, announce the basketball games and get paid for doing all the things I loved,” says Gomez, who now lives in Cherry Hill. “But on that day, it was chaos all around us, as you can imagine, but it was also on that day that I saw true leadership in the principal there.”

“It was leadership that had nothing to do with instruction or curriculum, but of holding the community together, informing us, being omnipresent, taking care of us and giving us clear instructions. On that day I realized there was more to life than just teaching English. It was clear I wanted to lead a school one day.”

Today, Gomez is the founding principal of Cristo Rey Philadelphia High School, one of a network of independent Catholic schools across the country. For its opening, the school’s founders raised an initial $5 million, and it now serves low-income students in North Philadelphia. The average annual household income for students in a family of four is $30,544. Currently, the student body includes 446 students in grades nine through 12; seven commute from Camden and Pennsauken, with the school providing transportation.

As founding principal, Gomez established the tone and culture of the school – hiring the entire faculty, setting criteria for student admissions and developing the curriculum. As the father of two elementary school students, Gomez says he is trying to create a school he’d be proud to have his children attend.

“Cristo Rey is for students who are highly motivated who couldn’t otherwise afford a college prep, independent school,” says Gomez. “This is a really tough place to go to school – it’s rigorous. It’s not easy, and it’s not for everyone. It’s very clear that college is the goal here.”

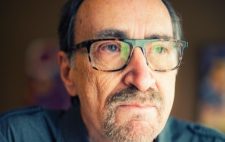

Michael Gomez with senior Jay Lloyd, who is heading to Widener in the fall

“We promised the students that if they worked hard, developed good habits in time management, resilience, grit, focus, and had the ability to look ahead to their future, they would all be accepted into college,” Gomez adds.

And so far, he is right. Cristo Rey Philadelphia’s first class will graduate this year, and all 86 graduates will attend a four-year college. The majority are the first in their families to attend college. Schools include Temple University, Fordham University, Loyola University Maryland, Cabrini College and Penn State.

Gomez notes that the school’s first class of ninth graders included 124 students, so they lost 38 students for various reasons, ranging from poor academic performance to behavior issues to a student’s family simply relocating. “It’s heartbreaking,” he says. “We make an emotional investment into these students. We promise to love and care for them, and when we lose them, for me, it feels like a failure.”

While the Cristo Rey network sets the core curriculum – English, math, history, and science – Gomez added Latin, theology, fitness and six AP courses. Similar to other high schools, extracurricular activities include the school newspaper, drama club, boys’ and girls’ sports teams and creative writing.

Unlike other high schools, Cristo Rey students must work one day each week at a local business, performing a variety of jobs, ranging from answering phones and filing to completing database entry or providing IT support. The employers – which include companies like Comcast, Deloitte, Independence Blue Cross and CHOP – each pay Cristo Rey $7,500 per student, covering about 60 percent of the student employee’s tuition. The rest of each student’s $12,000 annual tuition comes from their families, who pay what they can afford, along with donations.

For many upperclassmen, working four years at one company gives them increased experience and opportunity. Gomez points to one senior who has worked for CHOP all four years and now works in a research lab conducting experiments alongside doctors and graduate students.

But critics argue that under the program, high school students miss 200 days of education. Gomez believes work experience gives students important and useful skills, including building relationships with adults in the workforce.

Gomez attributes part of the school’s success to his cultivation of teachers, who he expects to serve as role models for students. For the first freshman class in 2012, more than 100 applicants were vetted for 14 teaching and staff positions. Gomez says he spent six months selecting the right teachers, who he now mentors. The one day per week when students are at work is spent on teacher development.

“I’m very good at hiring awesome teachers who are energetic and want to change the world, who don’t whine and want to be coached in becoming better teachers,” says Gomez. “My most important role is to be sure I am surrounding the students with adults who will love them wholeheartedly, will be role models in their lives and who will treat them as sacred.”

Before establishing Cristo Rey, Gomez spent six years as the principal of St. Joseph’s Preparatory School in Philadelphia, a private school serving primarily affluent students. He made the move, he says, because “I wanted to show that inner-city kids who come from challenging backgrounds can go to an awesome school and can go to college.”

Despite the differences in the two student bodies, Gomez says there are many similarities.

“All students come with an invisible backpack, things they bring from their families and their neighborhoods that we can’t see on the outside,” he says. “They all have emotional struggles, because they are adolescents growing up in a tough world. The difference is the St. Joe’s Prep students might have received support for these things. We are creating a school where we are trying to care for students’ academic success, but also some of those things that might not have been cared about before they got here.”

Gomez incorporates counseling into every school day at Cristo Rey. Students meet with a counselor in small groups to share concerns. “We do this so students feel they are a part of a small team with an adult listening to them,” says Gomez. “I think this helps our retention rate.”

Michael Gomez encourages students to drop by his office to chat

The principal also encourages students to drop by his office to chat. “I’ve talked about academic struggles, but I’ve also heard about their parents’ behavior, neighborhood, boyfriends, girlfriends and college choices,” he says. “Students feel heard in my office.”

In a few instances, those conversations have led to Gomez and a counselor visiting the student’s home, mostly to discuss the student’s academic performance or behavior in school.

“We wanted to go into a family’s comfort zone to sit on their couch to talk,” he says. “One conversation was about keeping the young person in school. We were able to do that, and she was accepted into college, so that was a success story. In another situation, the student failed out.”

Gomez and his faculty understand those invisible backpacks could present additional challenges once their students are on their own in college, but “we’ve done our best to get them college-ready,” he says.

“Like any college prep school, there are students who are going to do better than others and students who are going to struggle. Since this is our first graduating class, each year we are going to get better at preparing them for college. This is a marathon, not a sprint.”