There are many ways traditions are passed through generations: A master basket maker – while weaving a basket – tells the story of the first basket made using traditional Lenape techniques. Mothers teach their daughters and sons African American hair artistry while styling their hair. The many special everyday moments that work their way through generations are the focus of Marion Jacobson and her team at Perkins Folklife Center. They are the documenters of the art of everyday life.

Q: What is the Perkins Folklife Center?

Started in 2016, the Perkins Folklife Center is responsible for protecting and supporting the wonderful art of everyday life. Back in the ’70s and ’80s, most states had a state Folklife director – somebody who would be in charge of collecting and documenting the state’s traditions, archiving them and supporting public programs. Many of them no longer exist. Today, the Perkins Folklife Center is one of a network of 5 folklife centers around the Garden State, all funded and sponsored by the New Jersey State Council on the Arts.

Q: What is “art of everyday life”?

It’s the million tiny acts and stories and beliefs and arts that function as social glue, even if they often escape our notice. It’s the South Indian mandala artist who swirls colored rice into a vibrant circular design at a South Indian Diwali celebration. And the dumbek (goblet drum) player at a Middle Eastern nightclub who synchronizes his beat to the undulating movements of the belly dancer.

Q: Why do you think studying folklife is important?

The power of folklore is the power of human connection. We’re studying the traditional ways of doing things in our everyday lives. A lot of people think, “Oh, folklore is just old stuff passed on,” but really, it’s a book worth living. It’s full of insights about human behavior, creativity and community. Besides stories, it includes dance, music, crafts, folk medicine and jokes. Even social media memes are now part of what is considered folklore. An artfully braided head turns heads, inviting us to stop and connect with an individual or group of people with whom we may not normally interact, maybe even challenge some stereotypes. Folklore asks us to act out our humanity, because it gets to the essence of what makes us human.

Q: How do you preserve something that’s “everyday”?

As folklorists, we value things like photos, food, all these materials that we incorporate into our celebrations. They become important to understanding and protecting local culture. So you have certain things that you want to do to preserve them, like archiving and making them available on social media.

Q: It seems like there’s a lot of culture to cover in South Jersey. Yes?

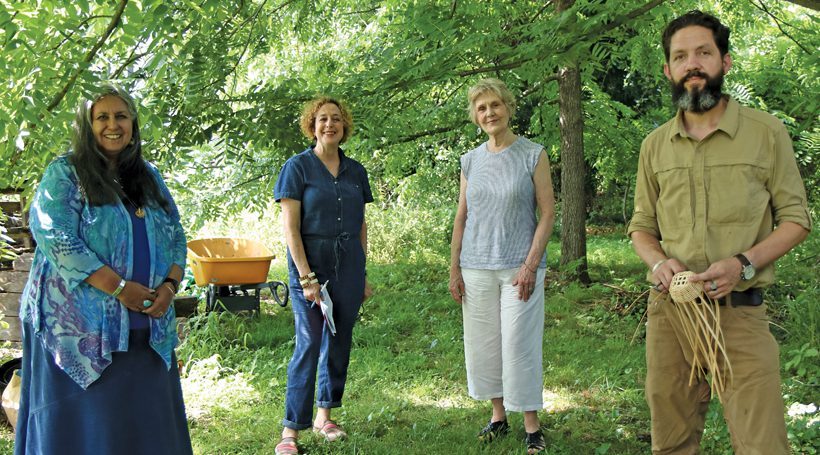

We serve such a broad area. To capture all the richness, we do a lot of fieldwork. Fieldwork is the craft of going into the communities, neighborhoods, people’s homes or workplaces and observing and documenting traditional ways of doing things. One day it could be a Native American “rematriation” ceremony on Native land in Bridgeton and the next day it could be a duck decoy competition in Tuckerton and the next, we’re in someone’s home documenting African American hair braiding.

Q: You call the people who are passing on their culture “tradition bearers.” How do you find them?

Some artists have already been working with other folklife centers, and some have been finding us since we’ve started spreading the word about the Folklife Center. We even have an open application process called “Perform with Perkins,” where people apply to become a folklife artist and partake in the different opportunities we have. But we also just go out in the field to find people.

Q: And how do you share these experiences with the community?

We do a ton of public programming. We have a constant turn of events, whether it’s workshops or educational programs. But it’s also about supporting the artists – the tradition bearers who may never have had the opportunity to present their art form on stage or at a big festival or even get paid for their work.

Q: What kind of support are you giving the artists?

Take Ritu Pandya sharing her Indian dance presentation. A lot happens before her performance. There are months of preparation, because the artist hasn’t necessarily been trained to do a stage presentation or teach a workshop. But they deserve to get support and feel confident and empowered enough to present. I share feedback from the audience, from my colleagues, and we’ll help them get grants too.

BONUS CONTENT

Q: What events do you have?

The biggest event we host each year is the World Stage: Dance It Out! Series, a showcase for large ensembles that represent the musically diverse communities of New Jersey and Philly. It’s 5 participatory dance workshops through the summer that take place on a rented dance floor outside. This year, we presented swing, Afro-Puerto Rican, Cumbia, Mid-Eastern and Bollywood music. Then in the fall and winter, we move inside for the House Concert series in our Moorestown living room. We’re about halfway through this year’s series. The next concert is on Feb. 9, presenting Magdaliz and Her Latin Ensemble Crisol.

Q: What do the educational programs look like?

The first part is what we call Folk Arts in Education, where we bring together folklife artists and teachers to connect with students and bring the important aspects of folklife into the curriculum. We’re going beyond the traditional assembly format. For example, in a program where we’ll bring a West African drummer to a school and have an assembly – we’re gonna go deeper. We want to raise students’ curiosity to the level where they’re able to ask questions, do critical thinking or have that ‘aha’ moment. That requires meetings with teachers, preparing lessons, aligning with state standards. In a way, we’re kind of an educational consulting arm.

Part two is called Folk & Traditional Arts at Home. It offers people who can’t leave their homes for whatever reason – because they’re elderly or disabled or immunocompromised – a way to have educational arts experiences in their homes. They’re basically customized mini residencies that can be hosted in-person or virtually. It could be singing The Beatles songs for somebody receiving memory care or a yoga and meditation session for people post-surgery.

Q: Why did you choose a career in folklore?

I spent a lot of time with my mom, who was my first folklore teacher. My mom spoke Yiddish, the language of Eastern European Jews. I decided I would be her “folklorist.” She wanted me to learn about our family traditions and our culture, there was that sense of nearly being wiped out but still holding on. I think all of us have some folklore in us – we’re curious.