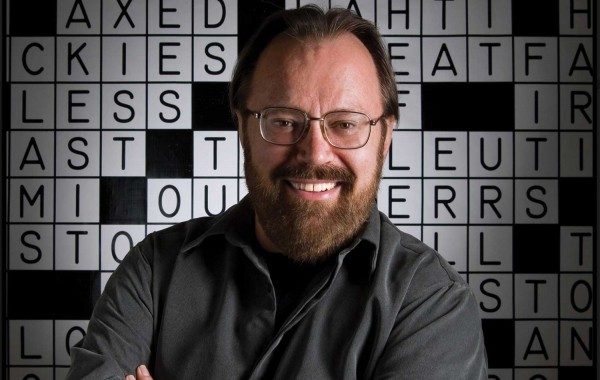

For 100 years, the crossword puzzle has challenged, frustrated and amused the brave souls who dare to tackle it. For much of that time, Merl Reagle, 64, has been a leading crossword creator. Designing his first puzzle when he was a first grader in Lindenwold, Reagle sharpened his skills over the years and eventually landed in the movie “Worldplay,” on FOX TV’s “The Simpsons” and even on Oprah’s couch. His love of words and the English language, combined with his quick wit, make Reagle’s Sunday puzzles a hit in 50 newspapers, including The Philadelphia Inquirer and The New York Times.

What made you create your first puzzle when you were 6 years old?

I always enjoyed building things like Tinkertoys and Lincoln Logs. When I found out what words were, I did the exact same thing with them, building little structures out of words. Somebody gave me grid paper, and I started building structures out of the names of the kids in my first-grade class. My mother said, “You’re just doing a caveman version of the things in the paper.” She showed me “the thing in the paper,” with its black squares and numbers. It was a very advanced version of what I was doing. I thought I’d just get as good at that as I was at my silly versions. It resulted in something irresistible to me: how you can get words to interlock in big, wide-open chunks of white space, and you can do it with common words. I like easy, common words, but tricky clues.

People may not realize that puzzles have rules. What are some of those rules?

Rules help separate the pros from the amateurs. Anybody can make a puzzle if you throw the black squares anywhere, but it takes some degree of craftsmanship to put the black squares in a symmetrical pattern. If you turn the crossword puzzle upside down, the arrangement of black squares stays the same. This is so the puzzle has an actual design that looks good on the page. That also means if you have certain long answers in the puzzle, they have to match up. If you have a 17-letter answer in the upper left, you also have a 17-letter answer in the lower right. It’s called rotational symmetry. The idea that there are pairs of theme answers all over the place gives the solver a leg up as to where the theme answers are. The solver knows they are in these opposite locations.

Other rules are that in America it’s three letters or more; we’re not allowed to do two-letter answers. You can’t have a letter in only one word – they have to be in words across and down. You can’t have islands of words separated from the rest. But, you can always break these rules depending on your puzzle theme. For example, on April Fools’ Day, puzzles will break the rules.

What’s the key to creating a great crossword puzzle?

I like doing themes based on something interesting. For example, every year the president pardons a turkey. My thought was: pardons him for what? What did the turkey do? You can’t just be pardoned for doing nothing. So I thought there must be some series of bird crimes that we don’t know about. I would just riff on the cross between bird references and crime. Maybe he started out just jay walking – not too bad. But then selling beer to mynahs and robin banks. Even the word illegal has eagle in it. At the end, of course, he wasn’t a flight risk! There are just jokes going off. Most people solve from the top down so I usually leave my punch line or best answer for last at the bottom.

How do you use your interest in word play in your puzzles?

I have a lot of curiosity about how the language works. To me, the English language is a massive playground, and I get lost in it every week. There are certain clichés we say that I wonder how they got together. For example, why do we say, “He’s a rank amateur?” How did rank get attached to amateur? Do they smell? Why is a hussy always brazen? What does “get along famously” mean? Why in romance novels is there “unbridled passion?”

Why do you think crossword puzzles are so popular?

Most people say it’s because it’s one of the few things that actually has an answer. People think, “My life usually has a lot of open-ended things, not so much black and white. But a crossword puzzle has a definite answer, and it kind of gives me hope in the morning that my day will go well if I can solve it.” But my personal thought is that crossword puzzles feed into that thing in your brain that wants a hint. Every answer you get helps you get another answer. All people want a little bit of help to get something done.

You spent time at the Berlin Farmers’ Market as a kid. How did that affect your passion for crossword puzzles?

That was one of my favorite things to do every Friday night with my dad. They had Sunday’s Philadelphia Inquirer there on Fridays, and I could never figure out how they knew what the news was going to be. They had the Sunday paper with the color comics and the crossword on a Friday night. They also had a stall where they were selling Hammond organs. I started learning organ when I was about 9 or 10. You could sit and play the organ, and I played old-fashioned tunes like “Ramona” and “Arkansas Traveler.” I loved going there for the crossword puzzles, the organ and spending time with my dad.

How did you end up appearing in the movie “Wordplay” in 2006?

A couple in Los Angeles, Patrick Creadon and his wife, Christine O’Malley, were big fans of The New York Times’ crossword and decided to do a documentary. They came to the [American Crossword Puzzle] tournament in 2005 in Stamford, Conn. I was there because I had a puzzle in it. I was one of the judges, and I was one of the commentators for the finals. I became the go-to guy when they had a question. When they finally cut the thing together, they sent it to the Sundance Film Festival. Out of 775 documentaries, they only pick 15, and “Wordplay” was one. They wanted to show how a puzzle was made from beginning to end. I was the one chosen to do that. In the movie, they show me making the puzzle; Will Shortz, the crossword puzzle editor for The New York Times, editing it; and it coming out in the paper. Then they have celebrities solving that puzzle, and they ask why they are crossword puzzle fans. So the puzzle that Jon Stewart and Bill Clinton are solving is my puzzle. We all went to Sundance and had an amazing time, and the documentary was picked up and got a good distribution deal. We toured the country with it, and it was a very heady experience.

It was because of “Wordplay” that “The Simpsons” happened and we were on Oprah. How did your appearance on “The Simpsons” come about?

The producer of “The Simpsons” saw “Wordplay.” He laid out an idea to the writers about doing an episode in which Lisa gets hooked on crosswords. The writers on “The Simpsons” are all word-game oriented – you can just tell by looking at the signs on the episodes. In this episode, Lisa enters a tournament and loses. Homer had bet against her, so he won lots of money, but she found out about it and disowned him. To win her back, he spent all his winnings on hiring Will Shortz and me to make a special crossword to apologize to her. I said just seven words in the show. I’ve been a cartoon fan for years, but I never dreamed of being in one, let alone on “The Simpsons.”

You recently wrote a crossword puzzle book for the game’s 100th anniversary. Among the 5,000 puzzles you’ve created, how did you choose your favorites?

I have 16 other books out, so these are a selection of the next puzzles. But, unlike other books, I also picked puzzles from the past that I never republished that have a story behind them. For example, I was making the puzzle for the San Francisco Examiner from 1985 to 2000. But, in 1990, April Fools’ Day happened to fall on a Sunday. So I thought I’d do a puzzle about the reason that I’m leaving San Francisco to go make puzzles for The New York Times. The puzzle was called Tearfully Yours and the long answers were things like “I’m moving to the Big Apple,” “I’ll miss everyone dearly,” “You can’t be funny forever,” and “Incidentally, April Fools!” A lot of people thought I really was going and the paper got a flood of letters. They devoted the entire letter section to the mail on this one puzzle. That’s when we realized there really are fans out there, and we could syndicate this puzzle. Unless I make a mistake, we don’t hear from them. That’s the puzzle that gave us the idea to go to other newspapers, including The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Newspapers are struggling to retain readership. Is the crossword puzzle being affected?

So far it hasn’t affected me that much, but they say it’s only a matter of time before a lot of these newspapers turn into tabloids or go completely online. If they do, we can still give them puzzles, because we already have an online presence. Though there’s something about the tactile sense of solving on paper that a lot of people like, especially older solvers. Unless that goes away, there will always be a market for a paper puzzle.