There’s a world-wide movement that taps into deep traditions of food, drink, history, culture and human connection – and it was born at a strip mall in Cherry Hill.

It’s called the Slow Drinks movement, and Marlton’s Danny Childs, a farmer and chef with a background in botany and anthropology, was at the center of it. His mission? To encourage everyone from homecooks to industry pros to transform botanical ingredients − whether foraged, grown in the garden or purchased from the store − into unique, local and seasonal beverages and cocktails.

It’s called the Slow Drinks movement, and Marlton’s Danny Childs, a farmer and chef with a background in botany and anthropology, was at the center of it. His mission? To encourage everyone from homecooks to industry pros to transform botanical ingredients − whether foraged, grown in the garden or purchased from the store − into unique, local and seasonal beverages and cocktails.

“At its core, the Slow Drinks movement is about reconnecting people with the natural world around them,” says Childs. “Whether through foraging for wild ingredients or supporting local farmers, the movement encourages a more thoughtful approach to what we drink.”

The Slow Drinks movement takes inspiration from the Italian-born Slow Foods movement, which began in Italy in 1986 as a response to the growing prevalence of fast food, specifically triggered by a McDonald’s that opened near the Spanish Steps in Rome. The movement emphasizes local, sustainable and thoughtful consumption as a way to promote traditional, regional cuisine, as well as sustainable farming practices.

The core principles of the Slow Food movement – and, subsequently, the Slow Drinks movement – are about enjoying food that is “good, clean and fair.” This means food that tastes good, is produced in a way that doesn’t harm the environment and provides fair conditions for both producers and consumers.

“Slow Drinks felt like the natural counterpart to the Slow Foods movement,” says Childs, who snatched up the @slowdrinks handle on Instagram, then sat on it for nine months. “It felt like I have this golden egg, and I don’t really know how to handle the responsibility that comes with this name.”

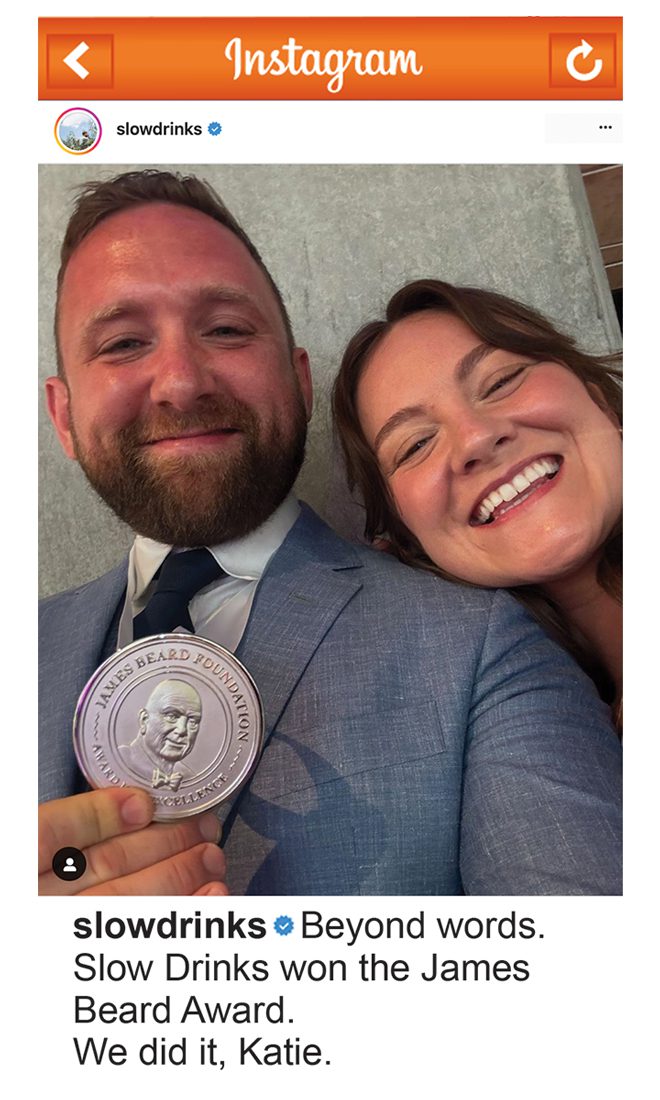

He started filling the page with Slow Drinks recipes, his wife did the photography, and the account took off. Interest in the Slow Drinks movement was there, he says. In 2017, he began to write what is now the James Beard Award-Winning recipe book “Slow Drinks: A field guide to foraging and fermenting seasonal sodas, botanical cocktails, homemade wines and more,” which he released last year.

Childs dug into his botanical background – both international and local – for inspiration. Early in his career, he conducted field work in South America with three different indigenous tribes to learn medicinal uses for their local plants before moving back to Marlton to start his own farm.

Living on the farm, Childs began exploring foraging and agriculture in South Jersey. This was more than just an education in food production. It became a way for him to reconnect with his local environment – its plants, history and culture. Then, when he began working as a chef at The Farm and Fisherman Tavern – a restaurant that focuses on using regional, seasonal and often foraged ingredients – he began to experiment with the surplus of ingredients from foraging and farming.

From these experiments came an idea: What if the same principles of Slow Food could be applied to drinks? (The answer was a resounding “yes.”)

Childs draws inspiration from the local landscape of South Jersey, where he can spot wild grapes, sumac, elderberries and even feral cranberries on a morning walk. The Slow Drinks movement, much like Slow Food, encourages a return to local ingredients, traditional methods of preparation and historical significance.

Danny Childs

“So much of our botanical history in South Jersey has been lost, but there are a million examples of culturally, medicinally and historically important botany in the area,” he says. “You can look outside almost anywhere and find a pine tree. Pine has a very distinct flavor, but also a very long history of medicinal use.”

Childs highlights plants with a use and a story. Sassafras, for example, once a major U.S. export and the original ingredient in root beer, was first created in New Jersey by Charles Elmer Hires and debuted at the Philadelphia Centennial Expo in 1876. These stories serve as a reminder that our botanical history is often closer than we think, he says.

“People are interested in these histories, but working in a restaurant, there’s only so much you could fit onto a menu,” says Childs. “It relies on a bartender or server to tell that story. That’s why the Slow Drinks movement was necessary.”

By using local ingredients in drinks, people can connect more deeply with their environment and their past, he says.

Slow Drinks has resonated with a wide audience, from bartenders to home enthusiasts – even those interested in mindful, non-alcoholic options, as many of the recipes can omit the alcohol without losing the substance. The process of foraging, fermenting and preserving ingredients offers a hands-on way for people to engage with their drinks.

“There’s something really rewarding about finding these ingredients yourself, bringing them in your kitchen and transforming them through these preservational processes,” says Childs. “You have much more of an investment and connection because you made them, you harvested them. It’s not like you’re going and buying a six pack of Coors Light. You’re crafting these with your own hands and your own palette.”

Slow Drinks has also gained international recognition. Over the last 8 years, childs has teamed up with the Slow Foods movement on International programming, including translating his book into Italian. He recently attended the Terra Madre Conference, a biannual slow food gathering represented by over 100 different countries, where they officially launched the Slow Drinks initiative as a direct counterpart to the Slow Food movement.

“At first, I was afraid of using the name Slow Drinks,” says Childs. “I wasn’t sure if they were going to embrace me. But they have been so encouraging and welcoming with it. It was never about who owned the idea – it was about sharing the same mission.”

Childs sees it as a way to uplift local economies, farmers and traditions worldwide.

“I’m connecting with the bartenders, farmers, foragers, home chefs and spirit companies around the country and around the world,” he says. “We’ve been putting together these offerings that really highlight the landscape and the food of that area. In every step of the equation, you’re kind of lifting up those little pieces of the economy along the way.”

Childs never expected to return to South Jersey as an adult, but the Slow Drinks Movement has been a full-circle moment for him, he says.

“This has allowed me to see my hometown through a whole new lens,” says Childs. “At the core of this movement is a love letter to South Jersey and the Mid Atlantic. We now see the initiative around the country and around the world, but it started right here.”