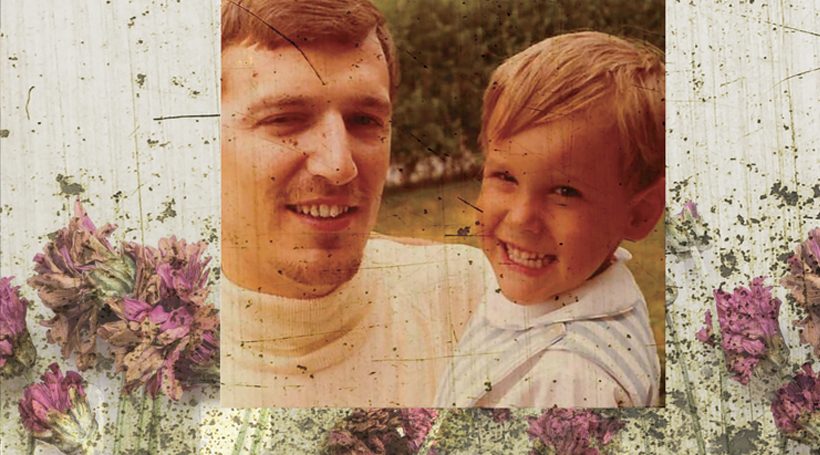

Photo above: Joseph Halsey with his dad James in 1971

Last year, New Jersey passed legislation that allows terminal patients to end their life on their own terms. Legislators make it clear this is not suicide. It’s something different, which many people have a hard time understanding – and accepting. But for families who have watched a terminal illness torment someone they love, there is nothing complicated about this. No one wants to help a family member die. And no one wants a family member to suffer every day for the rest of their life. Those who have lived this conflict say this law is a very sad, deeply painful necessity. They want you to understand that for them, this law is about love.

Just after James Halsey was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in the 1990s, he mailed a copy of Dr. Jack Kevorkian’s book to his son Joseph and said, “Let’s talk.” Kevorkian, often called “Dr. Death” by the media, was a proponent of physician-assisted suicide who was convicted and imprisoned for 8 years for helping his patients die.

“After Dr. Kevorkian went to jail, my dad changed his plans,” says Joseph. “He said, ‘We can’t have you getting in trouble.’ But if I could have helped him at the end, and it wasn’t illegal, he would have asked and I would have done it.”

“People are one bad death away from supporting this option.”

Joseph Halsey; Photo by David Michael Howarth

In August of 2019, New Jersey became the eighth state to make it legal for terminally ill residents to be prescribed life-ending medication by their physician. In the first months after the passage of the Medical Aid in Dying for the Terminally Ill Act, 6 men and 6 women in the state ended their lives under the law’s provisions.

The act, sponsored by New Jersey General Assemblyman John Burzichelli, allows a resident who is at least 18 years old, is mentally capable of making healthcare decisions, and has been diagnosed with a terminal illness with a prognosis of less than 6 months, to request aid-in-dying medication. After a number of additional steps are satisfied, the patient can receive and self-administer the medication, which is meant to put them to sleep before painlessly stopping the heart.

“The law says if a NJ resident under these specific circumstances wants to make this choice, they can have help,” Burzichelli says. Before its passage, such a death might be ruled a suicide, and people who help others commit suicide are breaking the law. “We don’t prosecute people who commit suicide. We prosecute people who assist in it, and we didn’t change that. We clarified, under these narrow circumstances, how this would work.”

But that’s not how it went for Joseph Halsey’s dad.

“He battled MS for 30 years,” says Halsey, who lives in Robbinsville, “and was losing a little every year. The last couple years he was bedridden. He would aspirate on his own fluids. Every 3 or 4 months, for years, he’d aspirate, we’d take him to the hospital to clear his lungs, he’d get a fever and go into a comatose state. The last time, when he came out, he said, ‘That’s the last time I’m doing this. Next time, I’m done.’ He decided to refuse treatment, and it was like, well, your lungs will fill with fluid in a slow painful way and there’s no way to stop it. It took 2 full weeks and you couldn’t dope him up enough. Can you imagine drowning for 2 weeks? To say it was extraordinarily painful is an understatement. Not just for him, but for us and the other people who loved him who had to watch.”

After his father’s death, Halsey became a staunch advocate for the Medical Aid in Dying Act, in New Jersey and beyond. “My father was the perfect example of someone who should have been able to take advantage of this,” he says. Halsey wrote essays and went to the statehouse during the debate period to share his family’s experience, and to say, unequivocally, that he wanted other people to have the choice his father didn’t.

“When you have a terminal illness, everyone needs a choice,” he says. “What people who haven’t lost someone like this don’t realize is that you don’t mourn their death, you remember their suffering. That’s what hurts you. My dad in pain, reaching out to me to help him, that image won’t leave my mind. Those are the things that come back to haunt you.”

Halsey, an actor who’s starred in a number of indie films, decided to step behind the lens, directing his first short film, titled “Choice: Mother,” to help people understand the intricacies of the law and the decision to end your life on your terms. The film showed at a number of film festivals, and garnered Halsey a directing award.

“I said, you know what, let’s start the conversation. There’s a room full of people at film festivals, and you get the opportunity to talk to all of them about something important,” he says. “I think now the work is educating people. People aren’t educated. You know how many people still think if you’re feeling blue you could go to the doc and say, ‘Hi, can you help me die?’”

The law has already survived several legal challenges, including one from a doctor, pharmacist and patient who claimed it violates the right to life and equal protections. A judge dismissed it, ruling the plaintiffs were not directly harmed or affected because the law is voluntary.

Burzichelli says that even now, more than a year after the law’s passage, his office gets a significant number of calls from people looking for additional information. Typically, he says, they’re referred to Compassion and Choices, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“Most of the time, people have really basic questions,” says Matt Whitaker, director of integrated programs at Compassion and Choices. “The first step is just having the conversation with your doctor and your family about your intention to go down this route. They just want to know what’s the next step. There’s still misinformation out there about what the law does and who it’s for and how the process works.”

One of the biggest misconceptions people often have, Whitaker says, is that the process of obtaining a life-ending prescription is simple. “People call and say, ‘I’m ready to do this, where do I go?’ or, ‘I’m going to New Jersey this week,’” he says. “But it’s only available to residents, and it’s a very involved process. Much of what we do is inform people about how important it is to have these conversations early, so you’re not having to go through this process in an emergent fashion. We tell people, even if you’re not terminally ill, but you think this is something you might want to have available to you way down the line if you should become ill, or if you just want to make sure the healthcare system you’re in has similar values, bring this up with your doctor at your regular check-ups.”

Since the process was legalized in New Jersey, Whitaker has fielded numerous calls from doctors looking for information. “It is a small number of people who ultimately make this decision, so this may only happen a handful of times in a 30-year career.”

Many of the people he talks to, Whitaker says, are trying to regain control over uncertainty and a scary diagnosis. They’ve seen their loved ones’ deaths, and they want theirs to be different.

“People are one bad death away from supporting this option,” he says. “We talk to people who are particularly adamant, and it’s because they helped a partner or a family member or friend at the end of their life, and saw that person wishing they had a sense of control.”

That’s true for Burzichelli. Back in 2013, when the law was first being considered, his sister-in-law Claudia, who has since passed away from cancer, told the committee about her father, who shot himself in the head after receiving a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. “There was a real education curve for a lot of people, including myself, to answer the question of where the law should be,” Burzichelli says. “Claudia went into great detail about how painful it was and how, knowing her father, he would’ve made that choice instead of the violence that happened. I’ve said publicly many times that this is not the right choice for everyone, but it’s a choice that should be available to everyone.”