Camden Invincible

Celebrating 10 years of community policing

Years ago, when community hearings got heated during discussions about replacing Camden’s police department with a new force – one with a radically different approach to public safety – there was one group who stood out among the vocal opponents to the change: criminals.

Years ago, when community hearings got heated during discussions about replacing Camden’s police department with a new force – one with a radically different approach to public safety – there was one group who stood out among the vocal opponents to the change: criminals.

“The criminals didn’t want any changes because they were doing just fine,” says Camden County Commissioner Director Louis Cappelli, Jr.

But despite the opposition to change, the momentous proposal to start a new public safety force from scratch successfully passed, thanks to its many supporters, including bipartisan lawmakers as well as clergy and other community leaders. From the first day officers from the county’s new Metro division hit Camden streets – May 1, 2013 to be exact – positive change was in the air.

“I remember specifically being on Mount Ephraim Avenue in Whitman Park with dozens of new police officers and, within five minutes, a drug dealer was arrested,” Cappelli says. “So that’s how it started.”

“At first, residents may have been hesitant and even suspicious about what was happening when police officers knocked on their doors to introduce themselves in the neighborhoods where they would be serving.” –Camden County Commissioner Director Louis Cappelli, Jr

“At first, residents may have been hesitant and even suspicious about what was happening when police officers knocked on their doors to introduce themselves in the neighborhoods where they would be serving,” Cappelli says. “But ultimately, relationships and trust grew, and a true partnership was formed between the residents of the city and members of the police department.”

“We couldn’t do it without the residents,” Cappelli adds. “They are our eyes and ears. So getting them to trust us, to share their concerns and information with us has been invaluable in preventing and fighting crime.”

Police officers play dodgeball at a recent community event

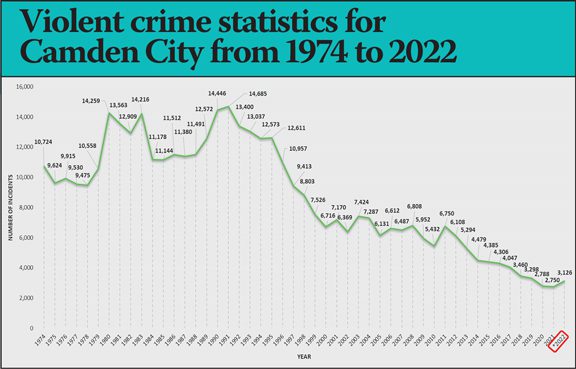

Once considered one of the most dangerous cities in America in the early 2010s, Camden’s turnaround can be attributed to the success of the county-led force,

Cappelli says. The overall crime rate has been reduced to 50-year lows. By the end of 2022, violent crime was down by 44%, and homicides were down by approximately 60% since the early 2010s.

A new officer is sworn in during police academy graduation last year

Murders, which hit a high of 67 in 2012, were down to 23 in both 2020 and 2021, but climbed to 28 in 2022. However, last year saw declines in both aggravated assaults and rapes, producing an overall lower violent crime rate. In addition, the city has seen a 62% decrease in shootings since 2012, the last full year of operation for the Camden City Police Department.

“Those who were involved in the county police force early on understood that everything we are working toward accomplishing would begin with improving public safety,” says U.S. Congressman Donald Norcross (D-1), who lobbied for the change when he was a state senator, and for the support of fellow state lawmakers and then-Gov. Chris Christie. “The idea of a mom sending her child to school into what some people called a war zone was not healthy for that child, nor was it healthy for the community at large. So through whatever means, we were going to make it happen.”

As it happened, a state statute was already on the books allowing counties to create police departments that towns could choose to opt into. Under the leadership of then-Mayor Dana Redd, the city chose that route, which triggered the dissolution of the old force and the rise of the new Metro department.

“We were taught that you don’t mess with the police, only bad guys dealt with them. We learned what community policing was by seeing it in action: Seeing police officers playing basketball with residents, walking around, and attending neighborhood cleanups, often in plain clothes.” -Camden Resident Tameeka Mason

The changeover was not immediate, recalls Cappelli. Under former Police Chief Scott Thomson, both the now-defunct Camden Police Department’s last chief and the first one to lead Metro, every officer from the disbanded force had to reapply for their jobs. They had to undergo new training, using the sanctity of human life as a guiding principle and emphasizing the use of restraint, even in incidents in which deadly force may have been legally justified but could be avoided.

Former Camden Mayor Dana Redd at the Metro 10-year commemoration event

Among those police officers, 156 of them – more than half – joined the ranks of the new 400-member Metro force. About 330 were assigned to the streets, says Capelli, noting that before the transition, fewer than a dozen officers would be on the streets during the hours when most crimes occurred. A new collective bargaining group was formed just months after the swearing in of Chief Thomson in 2013, offering competitive wages for the department’s members.

The city is now safer, which has opened doors for some $3 billion of private and public money in investments in the past decade, Cappelli notes. Moreover, Metro is considered a model department, with public safety leaders across the country looking to Camden for advice about community policing – not just as a means of reducing crime but also to flip an entrenched narrative: That the presence of police can only mean that something bad is happening.

Camden resident Tameeka Mason recalls how, a decade ago, the sudden presence of police on foot, on bikes or going door to door in an effort to get to know residents was a true culture shock.

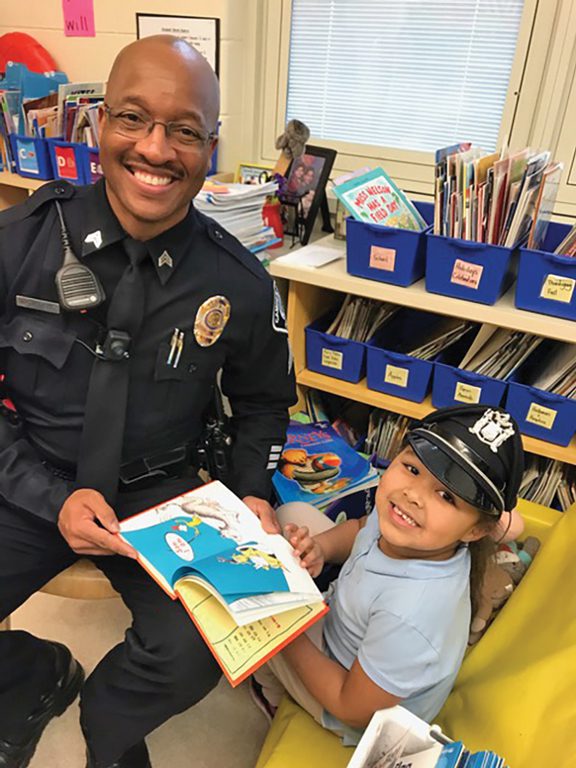

Lt. Terrell Watkins reading to a Camden student

“We were taught that you don’t mess with the police, only bad guys dealt with them,” says Mason, who was raised in North Camden. “We learned what community policing was by seeing it in action: Seeing police officers playing basketball with residents, walking around and attending neighborhood cleanups, often in plain clothes.”

Unlike her parents, who sealed off the family’s front patio in the old days, Mason and her neighbors now regularly enjoy each other’s company on their front porches.

“It used to be that if there were a bunch of guys gathered in the streets, the perception was they were doing something illegal,” says Mason, executive director of One Camden, a nonprofit organization where families can learn about and apply to Camden public schools. “Well, a couple days ago there were guys hanging out on State Street, and the police came over to ask if they needed anything. And my neighbors were like, ‘This is what we’re talking about.’ Folks have bought into community policing. It’s not perfect. We still have a long way to go, but it’s been a monumental change so far.”

Before, during and after the start of the Metro force

Camden County Police Chief Gabriel Rodriguez at the Metro force 10-year commemoration event

If the “Camden Invincible” mural that greets drivers on Admiral Wilson Boulevard.perfectly captures the vibe of the city today, it is also a reminder of just how far Camden has come in the past 10 years.

Before the Metro police department took shape, many considered the 9-square-mile city unfixable. Following years in which the once proud manufacturing city on the Delaware River was bleeding population and jobs in the ’50s and ’60s, the Great Recession of 2008 brought another sharp blow. By 2010, the city was broke. A budget shortfall in 2011 resulted in the lay off of 46 percent of the city’s police department. A year later, there were a total of 67 homicides, 172 shooting victims and some 175 open-air drug markets in operation.

City and county officials sat down with police union leaders at the time to discuss the idea of changing tactics to deal with the bleak circumstances. But those talks went nowhere, says Camden County Commissioner Louis Cappelli Jr..

With support from state and federal lawmakers and by receiving grants from think tanks working on police reform, the Metro police officers underwent training that supported community policing methods and received new technology that greatly enhanced the force’s ability to fight crime, often even before it happened. Among the improvements, ShotSpotter is an acoustic gunshot detection system that alerts police of virtually all gunfire activity within city limits. Its use enables fast, precise response, improved evidence collection and helps build trust, Cappelli says.

The force’s 24-hour command center features video monitors that play camera footage from around the city and a board listing the current locations of every police officer on duty. An adjacent map pinpoints them, along with the locations of calls to police. Officers also monitor social media and act quickly on tips from citizens, Cappelli says.

The dramatic results that occurred after the new force began caught the eye of prominent leaders, including President Barack Obama. During his visit in 2015, Obama called Camden a “symbol of promise for the nation” and praised the improved relations between officers and residents.

Efforts of the Metro police went viral for a good reason at the height of the pandemic, when Black Lives Matter rallies and some protests broke out in cities nationwide following the murder of George Floyd. Camden was one of the few cities that saw no riots, and Chief Joseph Wysocki was photographed in full uniform at the head of a march in Camden, helping to hold a Black Lives Matter banner and walking in solidarity with marchers.

“After that, I can’t tell you how many times I got requests to discuss the Metro force, and not just from within the United States. There was worldwide interest in community policing and what Camden had done,” says US Representative Donald Norcross (D-1).

Another proud moment for the city was when Gabriel Rodriguez was sworn in as chief in late 2020. Rodriguez, 40, who started his policing career as a 19-year old in the now-defunct city force, was the first city native to take the helm.

“We always talked about how it would be a major milestone when we will be able to appoint a chief who actually grew up in Camden City,” says Cappelli. “Having had Gabe move up the ranks to achieve this goal is something we’re very excited about.”

Last year, Janell Simpson, also a Camden native and longtime officer, became the first woman and first Latina to reach the rank of deputy chief. And the department has continued to hire local residents after lawmakers successfully lobbied the state government to drop a requirement that prospective hires take a civil-service exam. The employment of minority officers has risen to 58 percent.

“Having taken part in the formation of this department even before it launched, through to today serving as its chief,

I have seen firsthand the hard work and dedication that has gone into building this as a law enforcement agency that local residents can be proud of and that is responsive to their needs and values, their trust and their ideas about how to make this city a better place to live,” says Chief Rodriguez. “I am grateful to the men and women of this department who have worked day and night to build bridges in our community and establish a level of trust with our community that we never knew under the former agency.”

“At first, residents may have been

“At first, residents may have been