On September 8, 1949, Charles Cohen lost his entire family when a veteran killed 12 people in Camden. It was the country’s first mass shooting, and the community was rocked and left shaken. Cohen was only 12, and was now alone.

Almost 70 years later, Cohen’s granddaughter was a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fl., when a 19-year-old former student shot and killed 17 people at the school. Her family, including her aunt, Robin Cogan, were relieved to learn she had been in a different building during the shooting. But the tragedy left the entire family – and that community – traumatized.

So Cogan, who grew up in the aftermath of her father’s tragedy and later experienced the aftershock of her niece’s terrifying brush with destruction, decided to take action.

“It’s not just the victims or the survivors that are affected, it’s everybody around that incident who were also witnesses,” says Cogan, who is nearing 30 years as a school nurse in the same city where her father experienced tragedy. “Our sense of safety is forever altered. I remember saying, ‘I have to do something as a school nurse, as a public health person.’”

“She told me she was having a hard time reconciling being a nurse, someone with a healing touch, and being the daughter of someone who had killed someone.”

After the Parkland shooting, Cogan turned to her newly created blog, dedicating some posts to gun violence prevention. The site, a conference assignment turned passion project, is appropriately named The Relentless School Nurse – a nod to her husband always saying she’s relentless in everything she does.

Since those first posts, Cogan has invited fellow school nurses to share their stories on the page. She has also taken her work offline, speaking at schools across the country and joining the advocacy group This is Our Lane, a healthcare professionals advisory council within the gun violence prevention organization, Brady (named for Jim Brady, Ronald Reagan’s press secretary who was shot in the head during an assassination attempt).

“There’s such a desperate need for this public health perspective in gun violence prevention,” Cogan says. “We solved so many other public health issues – seat belts, car seats, smoking. Public health plays an essential role.”

The Surgeon General agrees. Earlier this year, he announced gun violence as a public health crisis. It’s a big win for This is Our Lane and other gun violence prevention advocacy groups, says Cogan, and could mean a boost in funding for research.

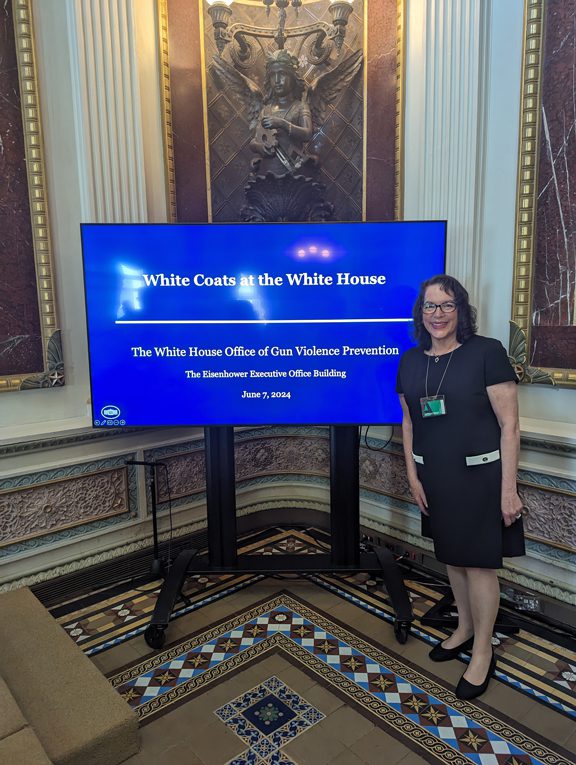

Cogan got to discuss that development with the Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murphy, when she and other This is Our Lane volunteers were invited to the White House earlier this year. In addition to dinner with Murphy, they met with the second gentleman, people from the office of gun violence prevention and representatives from Brady.

“It was one of the most thrilling days of my life,” she says. “I walked away with an incredible sense of camaraderie and hope. This is public health at its best, keeping children and the community safe.”

For Cogan, safety is what this work is about – it’s not about taking back guns. “You have a right to own a gun,” she says. “So what do you do as a gun owner to have that privilege and to keep other people, and other people’s children, safe around your weapons?”

The answer, she says, is practice safe gun storage. Meaning, guns are locked away and unloaded.

Each day, 8 children are unintentionally injured or killed by a firearm, Cogan says. She and her colleagues, along with other gun violence prevention advocates, are working to change that statistic by making safe gun storage a regular topic of conversation, especially for parents.

Cogan paints a picture of a world where the topic is built into curriculums at school, discussed at pediatric appointments, demonstrated in Hollywood projects, and even a standard on the list of questions to ask when setting up a playdate, just like parents do with aggressive animals and food allergies today.

“We have to talk about it,” she says. “We normalized mass shootings, why can’t we normalize keeping kids safe?”

Those kids, says Cogan, are also pushing for change when it comes to gun violence prevention. Often referred to as generation lockdown, students who were raised on active shooter drills have created organizations like Students Demand Action to put pressure on the adults who run things.

“They march and they write letters and they’re activists, because what have we done?” Cogan says. “Who are we as a country that we won’t protect our kids?”

In a field that can be incredibly contentious and confrontational, Cogan relies on data and lived experience to urge people who disagree with her to look at the issue from a different perspective. And while she does encounter some confrontational energy at times – especially on X, formerly Twitter – she also makes genuine connections with people who are, like her, dealing with fallout of mass shootings.

After speaking last year at the National Association of School Nurses conference – the same conference where she started her blog – Cogan was approached by a woman who quietly admitted, “My mother was a shooter.”

“Her mother had killed her father,” says Cogan. “She told me she was having a hard time reconciling being a nurse, someone with a healing touch, and being the daughter of someone who had killed someone. It wasn’t until my talk about safety, specifically safe storage, that she could face that part of her.”

As a Preschool nurse in the Camden School District, Cogan is also reminded of her family’s history on a daily basis. She didn’t visit the site of the shootings until after her father died, though. It was then she realized the site was just down the street from a school she had passed many times over the years.

“I try not to go down there,” she says. “It never escapes me that I’m working in the city where my father’s family was killed. I do this work for my dad and my family. You can’t go anywhere that is safe at the moment – supermarkets, places of worship, a school library, a mall. My goal is to reclaim those safe spaces.”