Photo: Tom Nikosey

Angus Gillespie

Angus Gillespie has spent years wandering deep into the most remote corners of the Pine Barrens, hunting the Jersey Devil. Or, at least, hunting for information about it. Gillespie is a folklorist who specializes in New Jersey’s oral history and traditions. A professor of American studies at Rutgers University, he has devoted decades of his career to the Jersey Devil in hopes of helping people understand that the creature is more than a spooky story, or the cartoon mascot of a hockey team. The Jersey Devil is part of the fabric of South Jersey, and to some, it’s very, very real.

Q: What makes the tale of the Jersey Devil folklore?

For something to be considered folklore, that means it’s passed along by word of mouth. It’s traditional; it’s passed on from father to son, mother to daughter, generation after generation. And it’s anonymous. We have no idea who the author of the Jersey Devil is. That’s simply lost in the mists of time.

Q: How did your study of the Jersey Devil begin?

When I first came to Rutgers in 1973, my department asked me to teach courses in folklore. I quickly figured out I better try to find some New Jersey examples. Pretty soon, talking to my students, it became very clear that a seminal example of New Jersey folklore would be the Jersey Devil.

Q: Were all your students familiar with the story?

It was only the South Jersey students who were familiar with the story. Of course, in the years since, the New Jersey Devils hockey team adopted the Jersey Devil as a symbol. And so, as a result, at least people have heard of it. But still, it’s only the students from dyed-in-the-wool South Jersey communities who really know anything about the true story.

Q: There have been lots of sightings over the years, but how did the early 20th century reports change things?

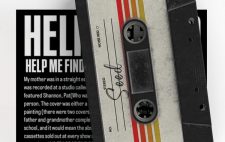

In the third week of January, 1909, there were a series of reported sightings of the Jersey Devil – a whole rash of sightings – that took place in Pemberton, Haddonfield, Collingswood, Moorestown and Riverside. And they were seeing footprints in the snow that were suspicious. The Philadelphia newspapers took an interest. But these city slicker reporters weren’t taking these sightings very seriously. They suspected that rural New Jersey farmers were kind of backwards and superstitious. And as a result, the write-ups were patronizing and the illustrations were almost comical. Some showed the Jersey Devil wearing a top hat, carrying a cane and smoking a pipe with a long serpentine tail. Another showed the Jersey Devil holding an umbrella while reading a newspaper story about himself.

These people in South Jersey weren’t stupid. They didn’t understand why it was treated like a joke. It wasn’t a joke to them. This was a serious threat. The Jersey Devil was known to slit the throats of babies in their cribs!

Q: How did that long-ago media coverage impact your work?

I come along 60, almost 70 years later, in the mid 1970s. I’m talking to South Jersey families, and I quickly catch on that they still have a profound mistrust of outsiders based on the 1909 experience. They didn’t want to talk about their true beliefs for fear of being made fun of.

I totally changed my approach. I would introduce myself by saying that I was interested in the old songs and stories this area was so well known for. I was very careful to discuss the weather and the farming and the fishing, neutral topics. And only after I felt that I’d won their trust and confidence, I might gently broach the topic of The Jersey Devil.

Q: So, since you’re the expert, would you tell the story of the Jersey Devil?

Jane Leeds and her husband Daniel had a house along the Mullica River, in kind of a swampy area. It was a strange and unusual family. A very large family. They had some 12 children. And Daniel Leeds, he was a good husband. He was a good provider. He was an excellent hunter and a good gardener. But he didn’t take that much interest in the children, and the whole burden of childcare fell on Jane Leeds.

One night, in 1734, she learned that she was pregnant with her 13th child. And as she was saying her bedtime prayers, in a moment of perhaps understandable weakness, she said, “Lord, let this one not be a child. Let this one be a devil!” Well, we now know that was a mistake, as on that terrible night in 1735, when Mother Leeds’ 13th child was born, it started as a perfectly normal, healthy, little baby boy with blond hair and blue eyes. But then, in the space of less than 20 minutes, something went terribly wrong.

That little baby grew to a creature the size of 2 full grown men; a creature with the head of a horse, the torso of a man, the feet of a goat, the wings of a bat and a long serpentine tail. It had a powerful chest and massive arms and biceps, covered with fur. At the end of each arm was a furry paw. At the end of each paw were long, bony fingers. At the end of each finger were razor sharp fingernails.

With one swipe of his right arm, the Jersey Devil slit the throat of the midwife, who collapsed in a pool of blood. The creature gave out a blood curdling scream, and escaped out the chimney into the Pines, where he’s terrified the people of South Jersey for the last 250 years.

Q: How do your students react to the story?

What I tell my students at Rutgers is the Jersey Devil is not a joke. It’s not a cartoon. It’s not a t-shirt or a bumper sticker. It’s a fearsome creature. Now, it’s become trivialized and commercialized, which is a shame.