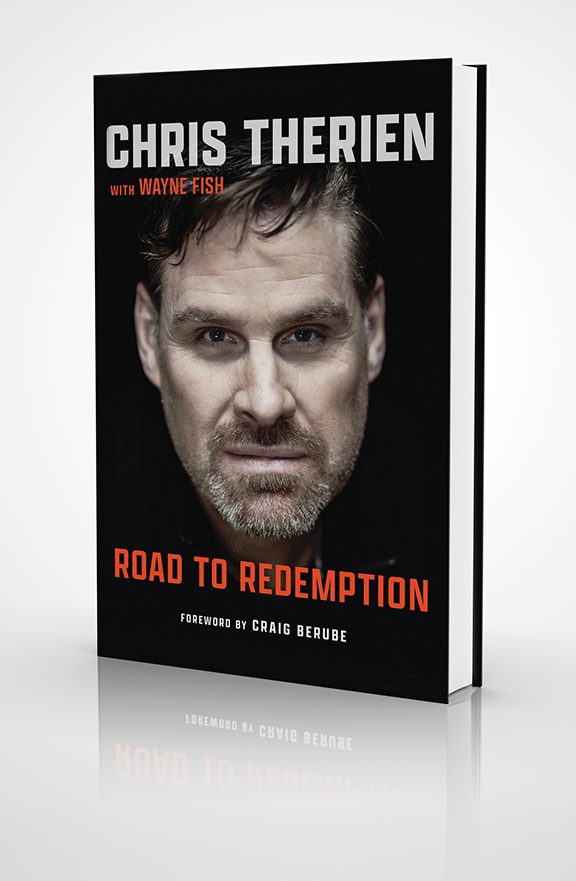

Chris Therien played 12 seasons for the Philadelphia Flyers – the longest of any defenseman in the team’s history. And while his career was distinguished, its end was marred by his hidden alcoholism, which turned out to be the biggest battle he ever faced – on or off the ice. In his latest memoir, Therien talks about his recovery, including his rehab at Caron Treatment Center. He chose this excerpt for SJ Mag readers.

![]()

I never put a lot of thought into what my life would be like without playing hockey and it’s probably just as well because alcohol had been clouding my judgment literally since the first day I got paid to play. After completing my stay at Caron, I had reached a day of reckoning. I was 35 years old, had another whole life in front of me, and wasn’t sure what the plan was.

My time at Caron was a good one and left me hopeful I was starting a road to recovery. During those 30 days, I met a lot of good people and lots of people from the Philadelphia area, which was cool. Before I got in there, they had to let people know a sports figure was coming in, and that person was Chris Therien, so please give him some space. At that point in my life, I was happy to talk to anybody, to make a new friend, and to try to leave what was left of my past life behind me, at least for the time being…

At Caron, I took a lot of great notes: I educated myself and did not waste time. I continued to work out in case I decided I wanted to go back and play in the NHL again. When I finally got out of Caron in early August, I realized fairly quickly that I probably wasn’t going to play again. New Jersey general manager Lou Lamoriello had asked me if I had any interest in joining the Devils because I roomed with his son at Providence. Lou had a soft spot for me because of what had happened to me that summer, with the alcohol rehab and the news my sister had died. To this day, I appreciate his outreach to me. To be honest, I thought it was brave of Lou, noble even, to consider me. I also had a tryout offer with the Columbus Blue Jackets. The Flyers had moved on from me. I don’t blame them at all. I wish I had done the work the summer before, not the summer after.

By all accounts, my hockey career was over. I was fine with that. Because of Sarah, I wasn’t in a place mentally where I was going to be the best version of myself. I might have been sober; I might have stayed sober for as long as it took. Frankly, I don’t know how long it would have been until I started living again.

When I got out of the treatment center, I felt more alone than I ever felt before. That became abundantly clear as training camps started to roll around just about a month after I got out of rehab. Camps were opening again, and players were reporting. I was alone, just three weeks sober. I had no job, my sister was gone, and my wife was ambivalent about our relationship because of my alcoholism. Plus, I had three kids who just didn’t understand what was going on. I was kind of in no-man’s land. It was a difficult time for me because getting sober was a hard thing to do and so was being sober. Everything changed, and I think a lot of things that people go through, you’re not really accustomed to going through them.

When I got out of the treatment center, I felt more alone than I ever felt before. That became abundantly clear as training camps started to roll around just about a month after I got out of rehab. Camps were opening again, and players were reporting. I was alone, just three weeks sober. I had no job, my sister was gone, and my wife was ambivalent about our relationship because of my alcoholism. Plus, I had three kids who just didn’t understand what was going on. I was kind of in no-man’s land. It was a difficult time for me because getting sober was a hard thing to do and so was being sober. Everything changed, and I think a lot of things that people go through, you’re not really accustomed to going through them.

When you get home, you feel safe, and that’s when you believe real change is going to happen. I looked around, and it seemed like everyone I played with for any length of time was also leaving the game: LeClair, Primeau, Stevenson, and Savage. We were all about the same age; we all kind of finished together. The retirements weren’t by design; it’s just the way it went. The NHL was turning into a younger game, making it even harder for the veterans to play with the new rules on limiting clutching and grabbing. The way I saw it, physicality was leaving the game. That was the beginning of the new era of hockey. I never thought the product got any better from that point on. People thought hockey was awesome up until 2004 and the lockout. Now it’s hard to find people who will say that about today’s game.

Fall began and I was attending some Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. But through these sessions, I was playing on my phone and not really engaged. At the same time, I was thinking, These people really aren’t for me. I couldn’t relate. What’s all this God stuff they’re talking about? What does God have to do with getting sober? Or staying sober? Actually, I thought it was kind of pathetic. To me, it was as simple as putting the bottle down and not drinking. It’s up to you. That was the athlete in me formulating that opinion, the competitor. It was more like me versus the alcohol. But even at that point I didn’t realize I wasn’t strong enough to beat it fully. I don’t know if an alcoholic ever becomes engaged enough to beat it forever. So that’s why you have to have a daily reprieve from it, where you start to feel better about yourself.

I didn’t do myself the service I needed to do. I was going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. In the meantime, Paul Holmgren was about to become the new general manager of the team after Clarke resigned the position early in the 2006–07 season. I had no job with the team, and I wasn’t looking for one. Homer shared some wisdom with me. He said part of the recovery was to admit to the mistakes you made and apologize to those you let down. He told me I should probably apologize to Clarke. I agreed I should go into his office and apologize to him. That’s what I did. I walked into Clarke’s office, and I said, “That person wasn’t me. If I did you wrong, that person wasn’t me.” If I had to pay for my actions, I just did by losing my only sibling, and the pain in me was probably more than a person could bear at that time.

It was good to communicate with management and say I was sorry, that wasn’t me. I was always the guy you believed in. Alcohol just took me over. I said the same thing to Holmgren, thanking him for believing in me and recognizing the issues I was facing for the past few years. Yet he never put any pressure on me.