Great works of art often reveal a hidden story of profound irony.

Consider this one: A young boy is introduced to art by his father, a classical painter living in Moorestown, just a few blocks from the home of a part-time artist who also happens to create and shape the modern myth of pro football in America – Steve Sabol, the president of NFL Films.

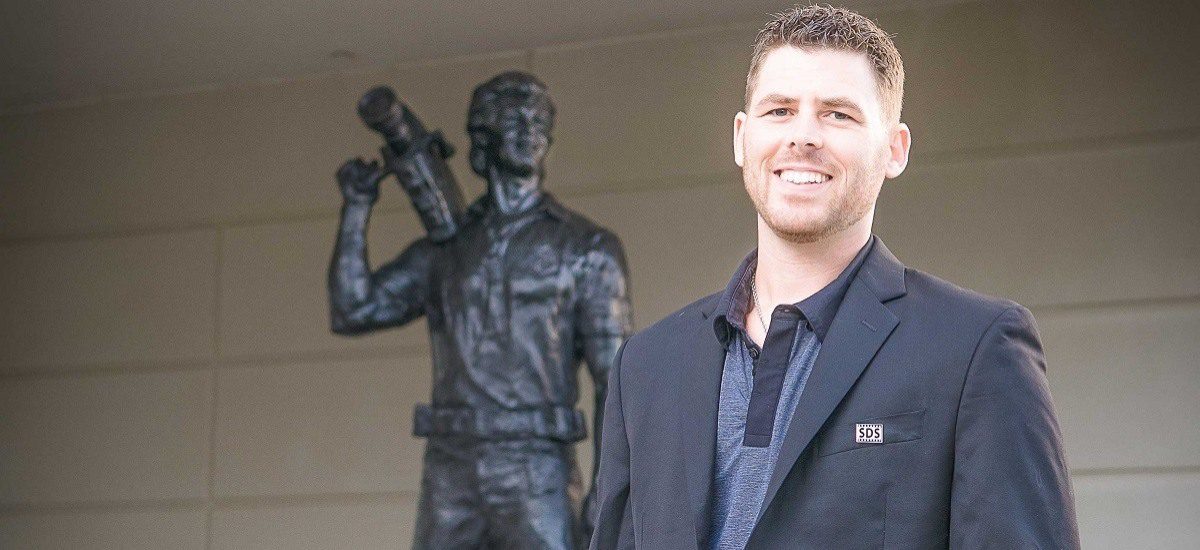

Like many kids of his generation, the young boy, Chad Fisher, grows up watching NFL Films and plays football all through school, but chooses the path of an artist, becoming one of the most celebrated young sculptors in the country.

And though he trained with his father in the shadow of a man he idolized, Fisher would never meet Sabol, who died of a brain tumor two years ago. That’s when Fisher, who was born in Woodbury and just turned 31 years old, was asked to become immersed in Sabol’s life and work, to help immortalize a man who influenced him in ways he would just begin to discover.

In August, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell came down from New York, snaking through the summer traffic on the New Jersey Turnpike, to help Sabol’s widow Penny and dozens of loyal NFL Films employees unveil Fisher’s 8-foot bronze statue of the man Goodell called “the soul of the NFL.”

Here is my conversation with the young artist.

SalPal: Steve Sabol was an artist himself – specializing in mixed media. He liked to quote the French painter Cézanne, who said, “All art is selected detail.” What does that mean to you and how did Sabol’s artistic vision influence you?

The 8-foot sculpture of Steve Sabol stands outside NFL Films In Mount Laurel

Chad Fisher: Beauty is in the restraint, meaning not every detail is necessary in a work of art. You are trying to convey a unified idea, thought or emotion. An artist, writer or film producer only needs the essentials; the rest is just noise.

All great artists masterfully select the essentials. They do this in a way so that no singular object or detail subtracts from the whole. It’s about the sum of the details harmonizing with one another. Steve did this. This is what gives expression to art; an individual has edited or selected something that can now transcend words or forms to become something more real, meaning the viewer can experience these ideas on a higher emotional level.

SalPal: Why did you want to sculpt a statue of Steve Sabol?

Fisher: I played football from the peewee level to high school ball, so the NFL, Steve Sabol and NFL Films were part of my childhood. As kids, my brother and I would watch “NFL Films Presents” and be in awe of the great NFL players: Dick Butkus, Joe Montana, John Elway, Barry Sanders. We would try to emulate them on the field and remembered their stories of perseverance, dedication, team, family, loss and victory during our own personal times of hardship and achievement.

Steve made a great game even better. He gave football a mythology.

SalPal: How did you go about getting the right artistic vision for the Sabol statue?

Fisher: I worked with Steve’s wife Penny Ashman and his longtime friend and assistant Hank McElwee. We started the project by reflecting on who Steve was. There were many stories – some were incredibly inspiring and most were very funny. As we talked more about Steve, a common spirit began to radiate through their words, which I would say is “Loved and admired by many, Steve is an NFL legend and artist whose vision helped create the NFL we have today.”

From there, Penny, Hank and myself combed through hundreds of photographs, discussing different gestures and asking ourselves, “Does this capture the essence of Steve?” We decided to portray Steve as a young cameraman, smiling, looking outward toward the horizon. From an artistic point of view this composition would be challenging and very exciting, and I was eager to start the clay immediately.

SalPal: You talk about Steve Sabol creating football “mythology,” and yet your sculpture of him is very mechanical – a man and the tools of his trade. Why is that?

Fisher: The word mythology here refers to Steve Sabol’s use of metaphors in his work. Metaphors or poetic thoughts create an impact on the audience and can help open their minds to imaginative and creative thoughts. The monument of Steve is more than just fabricated bronze that resembles Steve Sabol. It’s a bronze monument that reaches the viewer on an emotional level. I’m trying very hard in every sculpture to capture the essence of a subject with metaphors, so that I may create with an emotional and spiritual presence.

SalPal: What inspired you to become a sculptor?

Fisher: When I was 7 years old my father, a classically trained painter, gave me my first art lessons. I would draw almost every day as a kid, copying comic books and cartoon characters. By the age of 16, I was studying at the Art Students League in New York City and wanted to become an illustrator.

In college my interest in illustration moved from two dimensions to three. The idea of creating forms, as opposed to the illusions on canvas, was ground breaking. I traveled the United States and Europe seeking the best training in classical figurative sculpture. I wanted to create a beautiful object that would give the viewer a point of reflection. I was, and still am, inspired by the great master sculptors – Praxiteles, Michelangelo, Bernini and Rodin.

SalPal: Steve Sabol had a close relationship with his father, Ed – he learned a lot from him. Same goes for you. You are close to your father, Francis, and learned from him. How do you think that helped to influence your creation of this sculpture?

Fisher: I was lucky both my father and my mother encouraged the study of the arts. They are proud parents, and it’s very special sharing the art achievements with my Dad.

My father and I are definitely close. I talk to my Dad just about every day and send pictures for critiques and to discuss progress on all projects. He’s pretty honest. He will not sugarcoat or hold back.

Watching Steve and his Dad on film I could relate somewhat and it definitely helped. Subjects are much easier to sculpt when you can relate to them. They already have a presence in your mind or you know how to find presence through your own experiences. Rodin once said it’s not difficult to make a quick drawing or sketch, they are very expressive. The difficult thing to do is hold on to an idea or emotion for an extended period of time and have it be expressive.

SalPal: What from your upbringing in South Jersey helped you become an artist?

Fisher: There is a renaissance of figurative art and training today. This interest in figurative art was lost for the last 60 years and with that, outside of a few exceptions, training available from 1940 to 1980 was mediocre at best. The revival of the figurative and classical art surrounds New Jersey. New York City, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. are home to some of the finest fine-art instructors and institutons in the world.

Currently, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York are pushing the figurative arts to incredible heights. Because a figurative movement was happening in my backyard, I was able to aggressively seek out authentic information and training in sculpture. I am fortunate, and I am proud to have grown up here.

My source of inspiration is my love for my wife and two daughters. We all enjoy the arts and painting. Drawing and sculpture are part of our everyday routine. I ask my wife Denise to critique all of my work. She has an incredible eye for unifying a composition. Our daughters sculpt with me often.

SalPal: Why do you think sports and art dovetail into such a neatly woven cultural fabric?

Fisher: Our society enjoys seeing or hearing something that is special and heroic. Those moments can be life-changing inspirations and uplifting to the human spirit. We as a culture take great delight in observing someone who has mastered their craft through authentic hard work.

In sports we hear about Michael Jordan spending many hours after practice working on his jump shot after winning three championships or Jerry Rice’s off-season hill workouts throughout his Hall of Fame career. There is also the virtuoso violinist who practiced thousands of hours to play with ease at the recent concert. Art and sports, like many things in life, give you what you put into them. Talent will only take you so far. It’s hard work plus a sincere drive that equals professional success.

SalPal: When NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell came down from NYC for the unveiling of your statue, he called Steve Sabol “the soul of the NFL.” How does your sculpture embody that description of Steve?

Fisher: With a camera and an incredible artistic vision, Steve Sabol changed how we view football and all sports today. As a former college athlete, Steve knew a great deal about football, and he saw the game from an artistic point of view. His dramatization of the game gave the NFL a voice and a soul.

My intentions were to create a monument of Steve Sabol that captured his heroic presence. “Big Steve,” that’s what my two daughters call the statue, stands strong at 8 feet tall in his pyramid pose. His feet are about shoulder-width apart and there is only a slight twist and tilt to his vertical torso. His arms and hands are athletic and strong as he rests the camera on his shoulder. As a former Mr. Philadelphia, Steve had a great physique and build, and was known to always hold the 25-pound camera on his shoulder. Hank from NFL Films, Steve’s longtime assistant, said that camera felt like 50 pounds by the end of the filming day, but when Steve Sabol was filming that camera never touched the ground.

Steve’s chest is broad and barrel-like as it tilts up to the sky with an upward gaze from his head to complement this action. His gesture is an external moment, looking outward toward the future as a young cameraman. Michelangelo and many other Italian masters believed the chest and eyes are the windows to the soul, and if you are to represent someone with care and respect, the chest and face should catch rays of sun from the sky.

SalPal: What is your next big project?

Fisher: I am creating a bronze statue of George Boker, the founder of the Union League. There will be an unveiling in May of 2015.