Steven Van Zandt’s life ended before his 35th birthday.

In 1984, after almost a decade of playing lead guitar with Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, and just as the group was reaching astronomic levels of stardom, Van Zandt – known to fans as “Little Stevie” – quit.

“It was instinctive and emotional, and irrational, really, at the time,” Van Zandt, 70, says of his choice to leave. “I was the boss in my own world before I joined up with Bruce. So, you’re now working with him to realize his vision, and the role changes. You become a valuable advisor, but you’re just a soldier, and that’s a different mindset, a different job. Still, when I left the E Street Band, I felt like my life was over.”

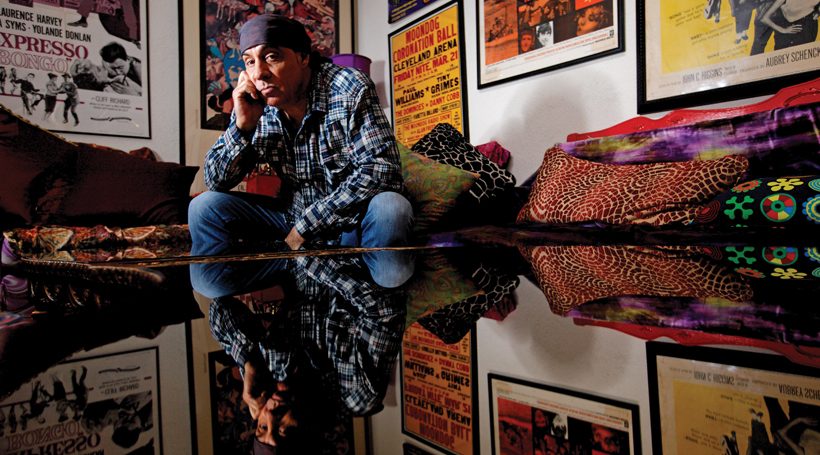

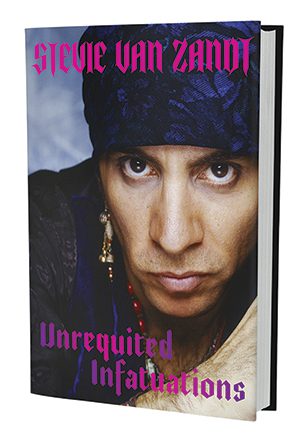

It wasn’t, of course. Not really. The long-time New Jersey resident spent the next 15 years playing with his own bands, Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul and The Lost Boys, acting in one of the most popular television shows in HBO’s history, establishing two new radio formats, and penning a memoir, “Unrequited Infatuations,” which was published in September.

In between, he moonlighted in diplomacy and politics. In the mid-1980s, he waded into the conflict in South Africa, forming an activist group called Artists United Against Apartheid, recording music opposing the regime and even traveling to South Africa to try to broker a peace agreement and, as he puts it, “bust Nelson Mandela out of jail.”

“I’d started this journey of self-education having to do with politics,” he says. “I began to realize [Americans] weren’t the heroes of democracy around the world, and was starting to feel some guilt and a sense of obligation to do something about it. And then because I left my job – I didn’t just change jobs, I ended my life – now I’m like, all in. I got nothin’ else to do. I have no other identity, no other job but to go to South Africa.”

Then, in the late 1990s, Van Zandt’s next opportunity came knocking.

“I was inducting The Rascals into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and the ceremony happened to be televised for the first time,” he recalls. David Chase, a veteran TV writer and producer, “happened to be watching TV and flicking around – this is how destiny works – and came across that channel at that moment. He decided he wanted some new faces in this new TV show of his, and I got the call.”

At the time, Chase was looking for a network to produce a new show he was writing about a mobster in therapy. Several had already passed by the time HBO greenlit the series. In 1997, Van Zandt and the rest of the cast filmed the pilot episode of “The Sopranos,” though it wouldn’t air until 1999.

“Three weeks after it was on the air, I’m walking down the street, and I look pretty damn different in the show,” Van Zandt says. “Everybody stopped me on the street talking about The Sopranos. Just like that, 25 years a rock star was out the window, like it never happened. And by the second season, it became ridiculously big. I had no intention of going back to music. I was completely embracing this whole new craft, like I was given a gift from the gods.”

For all 6 seasons, Van Zandt played Silvio Dante, right-hand man and consigliere to the late James Gandolfini’s Tony Soprano.

“I think my role evolved along the way as David picked up on me and Jimmy’s relationship off-screen,” Van Zandt says. The 2 sons of New Jersey grew close.

“Neither of us were really craving the limelight. I’m a sideman, he was a character actor, and we bonded over that. Before you know it, without really being conscious of it, I assumed the role I’d had with Bruce Springsteen my whole life. I knew what it was like to be the only guy the boss could trust, who doesn’t fear the boss, who could bring the boss bad news. Every boss, every superstar, everybody successful in the world should have one guy from the old neighborhood who isn’t afraid and will tell them the truth.”

Bruce Springsteen & Steven Van Zandt perform in NYC in 2007 / Alamy Stock Photo

As it turned out, Springsteen still needed Van Zandt to be that guy for him, too. In 1999, just as The Sopranos was becoming a cultural phenomenon, he decided to get the band back together.

“I left under emotional circumstances, and it felt like we needed some closure there,” Van Zandt says. That closure came when he officially rejoined the E Street Band. “I had said what I wanted to say and done what I wanted to do on my own. We never lost touch either. We’ve been best friends for 50 years. So it’s not like it was that big a stretch to get back together.”

Of course, he’d been gone for 15 years, and some things had changed.

“It took a minute to adjust to the fact that Nils Lofgren had replaced me on guitar, and Patti Scialfa had replaced my vocal parts,” he says. “So there was a moment of ok, how do we adjust? And then I realized my role: the guitar playing is the least important part. My role is to be the best friend. And people always ask, ‘Are you worried about being replaced?’ And I always say I can’t be. You don’t have that many friends for 50 years.”

These are things Van Zandt came to fully understand recently, he says, as he was recounting those decades in “Unrequited Infatuations.”

“The purpose of the whole book is hindsight – going back and not only reliving and recounting what was going on, but also getting a chance to maybe analyze things in a way I hadn’t at the time. It’s been a gift,” he says.

“The purpose of the whole book is hindsight – going back and not only reliving and recounting what was going on, but also getting a chance to maybe analyze things in a way I hadn’t at the time. It’s been a gift,” he says.

Part of his decision to leave the band in the first place, Van Zandt explains, was the transformation he watched Springsteen make between the release of “Born to Run” and the second album, “Darkness on the Edge of Town.” His longtime friend was suddenly “playing a character,” and it rubbed Van Zandt all wrong. Now close to 40 years later, he sees things differently.

“At the time I was just trying to make the best music we could make, and my complete concentration was on that,” he says. “Bruce was going through this enormous identity change, and I wasn’t really particularly paying attention to that. But it wasn’t about self-indulgence or fear of success…it was actually stuff he was really grappling with, having to do with changing his public identity.”

That was just one in a series of revelations Van Zandt says he had while writing the memoir.

James Gandolfini, Steven Van Zandt and Tony Sirico of HBO’s “The Sopranos” / Entertainment Pictures

“It was like therapy,” he says. “I came to peace with it, and it was a wonderful sort of relief, a reprieve.”

He also realized that striking out on his own all those years ago wasn’t necessarily the public career suicide he’s always seen it as, and that’s one of the major lessons he hopes people will take away from the narrative.

“That disappointment, frustration, life not working out the way one would hope – I think that happens to a lot of people,” he says. “So I hope my story is more inspirational, because everything I’ve accomplished happened after I thought my life was over.”

In recent years, Van Zandt has mostly stayed out of politics, both international and domestic. Instead, he’s focused his activism on the music world.

“All that intensity and focus went into saving the endangered species of rock ‘n’ roll over these last 20 years,” he says. “Suddenly, bean counters and accountants are running the world. They like a nice consistent bottom line, and rock ‘n’ roll is a bit erratic.”

To preserve it, Van Zandt launched initiatives like TeachRock, a free music history curriculum endorsed by the New Jersey School Boards Association and the National Association for Music Education. He’s also started 2 new radio channels on SiriusXM, including the popular Underground Garage, which he says has “introduced 1,000 new bands in the last 20 years.”

And of course, he continues to play and tour with Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. They’re a family, and that’s not something he plans to give up. Not ever again.

“As long as I’m standing next to Bruce, it’s a band,” he says. “We have an interaction that happens on-stage, it happens off-stage, and it’s beyond the music. It’s the posse, the team, the friendship, the family. And that’s what people respond to – to the friendship they wish they had, or the family they want.”