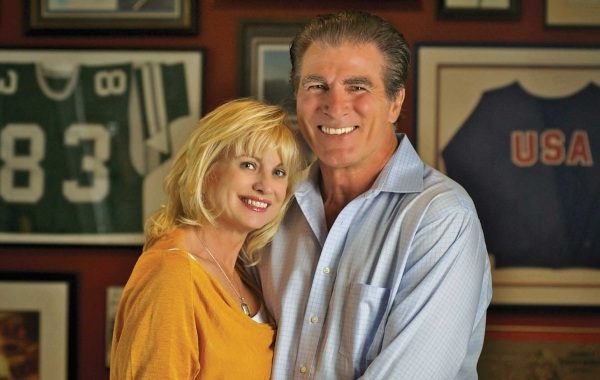

You’ll remember Vince Papale, whose time as a Philadelphia Eagle became the inspiration for the Disney movie Invincible. But Vince is also an author and motivational speaker who tours the country to share his personal stories and messages of strength and hope. Vince and his wife, Janet – a former member of the USA World Gymnastics team – have just released a new book, “Be Invincible!”, where they speak candidly about life, health, success and sports. Vince and Janet have chosen this excerpt for SJ readers:

You’ll remember Vince Papale, whose time as a Philadelphia Eagle became the inspiration for the Disney movie Invincible. But Vince is also an author and motivational speaker who tours the country to share his personal stories and messages of strength and hope. Vince and his wife, Janet – a former member of the USA World Gymnastics team – have just released a new book, “Be Invincible!”, where they speak candidly about life, health, success and sports. Vince and Janet have chosen this excerpt for SJ readers:

“Dictionary is the only place that success comes before work. Hard work is the price we must pay for success.”

–Vince Lombardi

When Dick Vermeil took over as head coach of the Philadelphia Eagles, the locker room and other team areas quickly became filled with signs displaying his favorite motivational sayings. One of my favorites and the one that sums up his attitude toward preparation for the game of football is, “Nobody ever drowned in sweat.”

It doesn’t take a lot of thinking to figure out the message. Hard work never killed anyone. Hard, relentless, exhaustive work was the cornerstone of Coach’s method of preparing his teams to win, or at least to compete. Remember, when he took over the team, the Eagles were barely competitive. A once-proud franchise was in shambles and fan support and confidence were wavering. That presents someone trying to improve the team with many problems. First, attendance tends to drop, which means lower revenues. With less money, you can’t sign many of the players you covet, can’t upgrade facilities and so on. Also, when a team is terrible, free agents usually don’t want to sign contracts. Everybody wants to join a winner.

That means that you’re stuck rebuilding with your existing roster plus other players who are hungry for jobs. Coach Vermeil knew that at least at first, we weren’t going to be able to compete with other teams on the basis of talent. We didn’t have it. But he was determined that we would surpass them in the areas we could control: fitness and conditioning, preparation, strategy and out-and-out effort. But to build that kind of a team, Coach needed to weed out the guys who weren’t willing to bleed and give every last bit of effort they had. So he designed his first training camp to separate the hungry, dedicated players from the ones just looking for a paycheck.

When I showed up for camp, I saw the “Nobody ever drowned in sweat” sign outside the locker room at Widener University. We started camp on July 3; remember, it was the bicentennial year. The next day, jets were flying over the stadium, but Vermeil was so focused on the camp that he kept wondering why all those planes were in the air. Finally someone said, “Dick, it’s the Fourth of July.” That’s how intense the atmosphere was. It was work, work and more work, and if you couldn’t take it, you went home.

He Can Kill Us, But He Can’t Eat Us

Camp was so merciless that it might have been “illegal” in some states. In most pro-training camps, the players would spend most of the time running plays and drills in light pads or no pads, which is cooler. But not with Vermeil. To him, if you weren’t in full pads, you really weren’t working. Well, full pads are hot and heavy, and in July and August they might as well weigh about a thousand pounds. We were always in full pads and helmets. We’d practice at what’s called a “thud tempo:” you would hit guys at full speed above the waist only and wrap them up. To prevent injuries, there was no tackling and no hitting below the waist. It didn’t matter, in full pads in the summer heat, it was pure hell.

Guys were falling over left and right from the heat and exhaustion. Coach’s philosophy was that if you needed to take your helmet off, you could walk off the field and just keep walking. All-Pro tackle Stan Walters famously asked him, “Are you trying to kill the first 45 players to find the last five?” He wasn’t trying to hurt us, of course. He was trying to see who wanted it the most. His thinking was that the guys who endured eight weeks of that torture would be the best conditioned, most disciplined, most passionate players in the league. They would be ready to endure any heat, cold or fatigue to win because they’d already done it in camp! Coach Vermeil put a lot of pressure on himself and his assistants during this time. As hard as we were working, they were working even harder.

The survivors started to say to each other, “He can kill us, but he can’t eat us.” When training was over for the day, we had to walk a half a mile up the street from the fieldhouse to the clubhouse. We called it the Bataan Death March. We weren’t allowed to drive our cars to practice, though sometimes fans would drive down and take us to the clubhouse. You’ve never seen anyone more grateful than an Eagles player after a Vermeil practice getting into an air-conditioned automobile. Sometimes kids would come down and carry our helmets for us; one of my “helmet boys” is now the PA announcer for the Philadelphia 76ers, Matt Cord. We’d give the kids tape or whatever we had on us, and they loved it.

I would go into training camp at 198 pounds and come out at 180. I would lose six to eight pounds in water weight in a single day. We’d all go to this place called the Campus Casino and drink beer right out of the pitcher. Then we’d go to the special teams meetings a little light headed.

The thing is, as punishing as those training camps were, they made us better. The players who survived and made the team had a feeling of camaraderie, because we knew we’d endured something that most people couldn’t. We knew we were fitter and tougher than any other NFL team. Personally, that 1976 camp made me work out even harder in the subsequent off-seasons so I could come to camp in peak shape and have a slightly easier experience. Even though we didn’t win a lot of games those first couple of seasons, there was a lot of pride. We knew we had put in the work and were giving it everything we had, and eventually it would pay off.

Invincible Moment

Spiritual teacher Matthew Joyce shares an extraordinary Invincible Moment from when he was just a kid: “When I was 11 years old I was skiing with a schoolmate. We came across a man in the snow with lots of blood everywhere. Three adults stood around the man in shock, doing nothing while he was bleeding to death. My friend and I asked what happened and learned he had taken a jump and impaled himself when he landed on the sharp end of his ski pole.

“Being Boy Scouts we set to work immediately. We sent one adult down to the lodge to get the Ski Patrol, one to block the jump so no one landed on the man, and the third to hike up the hill to direct the Ski Patrol. Then we treated the man for shock and applied pressure to stop the bleeding. All the while the adults were telling us what couldn’t be done. But we had our first aid merit badges, we were boy scouts, and we were prepared. We didn’t listen because we felt invincible.

“We ended up saving the man’s life. He’d punctured his femoral artery and if not for our immediate actions would have bled to death before the Ski Patrol arrived. We later received commendation from the Ski Patrol, from the Boy Scouts, and were written up in the newspaper. It was a long time ago, but it changed my mindset about what is possible.”