Ellen J. Green

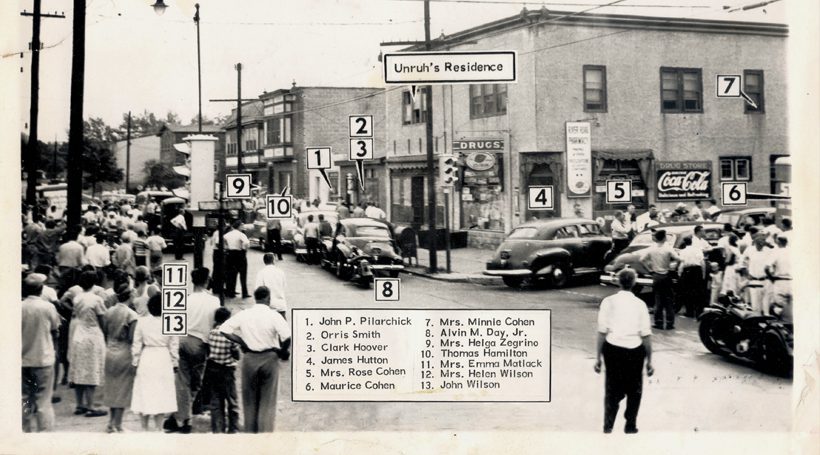

Before Columbine and Sandy Hook, before tragedy regularly graced our nation’s headlines and fueled the grief of our collective consciousness, there was Howard Unruh. On September 6, 1949, this soft-spoken 28-year-old picked up a semi-automatic Luger and proceeded to gun down 13 of his South Jersey neighbors. It was the first recorded mass murder in our nation’s history. Not only did no one understand it, no one saw it coming.

The chilling story is told in Ellen J. Green’s newest book, “Murder in the Neighborhood.” It’s a true story that reads like fiction, perhaps because Green is a fiction novelist.

“I really had no intention of writing this book,” says Green who resides in Haddon Twp. “I had finished 4 suspense novels, and was playing with different ideas for the fifth. I had heard about the Howard Unruh incident in Camden from my mother. Because I live in the area, a lot of people know about it or are connected with it. It always intrigued me.”

Green is a mental health professional who has worked in the Camden corrections system for 19 years now. She couldn’t seem to get the story out of her head and decided to get in her car and visit the crime scene. Green met the owner of the building where 3 of the murders took place, and even got a private tour.

“Those apartments had been sealed for 60+ years,” she says. “Nobody had been in or out. The doors were still there but they had cemented the windows. The new owner had just unsealed them and she took me through. It was like walking back in time.”

That was the turning point. Green was fascinated. She spent the next 2 years researching the story. She poured over records and interviews. She tracked down people at the scene and family members. She enlisted the help of a forensic psychiatrist, Dr. Peter Brancato, to analyze Unruh. Then she sat down to write the book. That’s where she hit a snag.

“I tried a straight nonfiction approach, and it wasn’t clicking,” she says. “I started and stopped several times. Through it all, the name Raymond Havens kept coming up. He was a 12-year-old boy who was friendly with Unruh because his father traded stamps with him, and Raymond was used as a conduit.” Green tried telling the story through Raymond’s eyes. The words flowed freely. At her editor’s suggestion, she later added the perspective of Unruh’s mother.

Howard Unruh, as Green learned, was gay. “The people I interviewed knew he was gay but it wasn’t anything that was discussed back then,” she says. “They called him names, such as sissy or Mary. He was a decorated war veteran and still they made fun of him on a regular basis.” That constant taunting took its toll.

The day before the murders, Unruh headed out of town to meet a male friend at the movies. The bus was late and they missed each other. Unruh sat in the theater alone.

“He felt as if he had failed every way a man could fail in 1949,” says Green. “He was never going to get married and have a traditional life that was going to make him happy. He was having difficulty finding and keeping a job. He was sitting in the theater stewing about the fact that this guy wasn’t there, and he didn’t know how to get in touch with him. He got on the bus and went back home.”

That’s when Unruh discovered something upsetting. The gate that he and his father built had been torn down by neighborhood bullies. It was the last straw. Early the next morning, he dressed in a brown suit, bow tie and combat boots.

He loaded his Luger pistol and waited for the shops to open. Then he walked downtown. “He cut through the back lot and he started with the cobbler shop,” says Green. “He just walked in and shot the cobbler in the head. There was a little boy who was there. He didn’t shoot the little boy. He went into the barber shop. He shot the barber. I believe from looking at all the evidence, he didn’t intend to kill the kid who was on the hobby horse. He didn’t know he’d shot him, but he did. He killed the little boy who was 6 years old, and he shot the barber. Then he headed for the drug store because he wanted to make sure that he got the Cohens. They were his primary target, and he knew the police were coming.”

Unruh shot James Hutton as he was coming out of the pharmacy to see what happened. Then he went upstairs and killed the three Cohen family members – Maurice and Rose Cohen and the grandmother, Minnie. He did not shoot 12-year-old Charles Cohen, either intentionally or because the boy was (presumably) hiding in a closet. The rampage continued. In all, 13 people would lose their lives that morning.

“When the police arrived, they seemed to be confused because this wasn’t a typical thing,” says Green. “There was certainly gun violence in 1949. But it was usually secondary to robbery or domestic disputes. People just walking down the street did not randomly shoot people.”

Green reflects on the tragic incident. “There were a lot of things that contributed to the superstorm that erupted that day,” she says. “I’m not saying that he’s not responsible but there were a lot of pieces that fell into place to make it happen that day.”

Unruh was ultimately diagnosed with schizophrenia and put in the Trenton Psychiatric Hospital where he remained until his death in 2009. Charles Cohen was sent to live with relatives in Philadelphia. He didn’t talk openly about the experience, and it wasn’t until his granddaughter Carly Novell saw a photo of her great grandparents that he shared the story.

She went on to attend Marjory Stoneman Douglass High School and was there the fateful day of the Parkland shootings. Novell hid in a closet with her friends for over an hour.

“All she could think about was that 68 years, 6 months and 20 days before, her grandfather had sat in a closet, probably much smaller than the one she was in, alone without the comfort of a hand to hold or a cell phone to communicate, while his entire family was being murdered within earshot,” according to the account in Green’s book.

“It is generational trauma,” says Green. Novell was grateful that her Pop-Pop didn’t have to see Parkland. He had passed away 9 years earlier. “He might not have survived it,” says Novell’s mother.

“This story of the first mass shooting in the U.S. holds the essence of every story of a mass shooting/mass shooter in this country,” says Green. “A person had access to weapons when they were feeling very disenfranchised, angry and wanted to vent in a way that would be felt by the largest number of people possible.”

“In Howard Unruh’s case, he killed 13 people in 12 minutes,” she says. “We have to have a national conversation about gun control and mental health, particularly concerning young people. We need to be asking the right questions: Why are these people feeling disenfranchised, particularly when so many of these shooters are coming from communities that provide opportunities? How can we target these people at the earliest stages and provide intervention? How can we better screen these people so they don’t have access to weapons? Why is this happening now at such an alarming rate? And how can we do this in a bipartisan way to affect actual change?”

“I don’t think I have the answers,” says Green, “but I think the answers are there.”