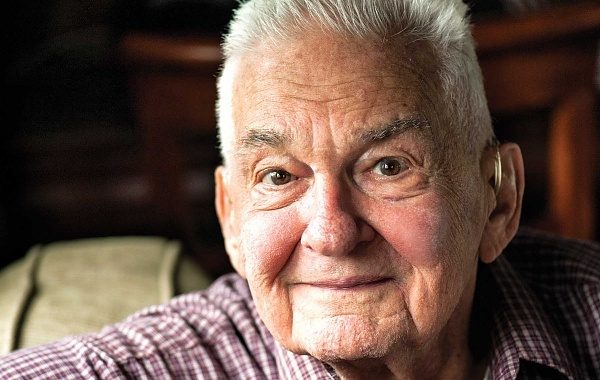

It all started when John Lauriello’s cardiologist wrote him a check for $1,000.

The 92-year-old Marine Corps veteran had been invited to go back to the tiny island of Iwo Jima, where he’d landed during the war 70 years earlier, but had brushed off the trip as an impossibility. On a whim, Lauriello asked his cardiologist if the doctor thought he was up to making the trip.

“It was just a regular checkup, and before we left, I asked, ‘Do you think I could go?’” Westmont’s Lauriello says. “He said, ‘Do you want to go? Then go. In fact, I’ll give you $1,000 toward the cost.’ And that was the start of the whole thing.”

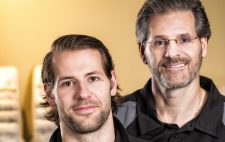

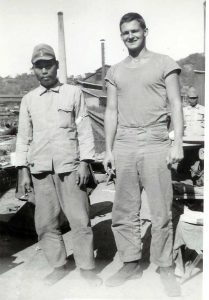

John Lauriello was 21 when he first landed on Iwo Jima, and he returned this year with his son Paul and grandson Talon

Lauriello’s travel costs were covered by the Iwo Jima Association of America, which takes a small number of veterans, chosen by lottery, back to the island each year for a ceremony to commemorate the five-week battle that took place there in 1945. But at 92, Lauriello couldn’t travel alone, and his son Paul, 46, would need $6,000 to make the trip.

“We’ve always looked at the trip back to the island and thought, ‘There’s no way, the price tag on it is just too high.’ We’ve never seen it as a possibility,” says Paul, a Medford resident. “But then they called my dad and said, ‘Your name’s been chosen, your trip is covered.’ But he can’t go alone, and that’s a predicament because I can’t afford it. I told him, ‘Dad, I don’t have $6,000 in the first place, let alone $6,000 to spend on a trip halfway around the world to this godforsaken island.’

“So I’m getting ready to call my dad and tell him I just don’t think it’ll work, and the cardiologist tells him, ‘Dude, you’re 91, go!’ and writes him a check for a thousand bucks. In 24 hours the whole thing snowballed out of control.”

Lauriello’s story went viral, first through local news coverage, and then when it was picked up by national newswires. Money began pouring in from supporters across the country. In two weeks, the family had raised more than $20,000 – enough to send both Paul and his 15-year-old son Talon. They used part of the leftover donations to sponsor another Iwo Jima veteran, a Navajo code talker from Arizona named Samuel Holiday, along with his granddaughter.

That gesture was particularly poignant for Lauriello, who vividly remembers his friendship with another code talker, Paul Kinlacheeny.

“Paul and I were on a ship in the Pacific together for 50 days, sleeping toe to toe,” Lauriello says. “One night, there was a food delivery we were unloading. Paul comes up with a can of sliced peaches, and he kind of looks at me and I give a little nod. He stashed them in the beams above our bunks. Well, a little while later they come over the loudspeaker and say, ‘Attention! Twenty-five percent of the food that was delivered is unaccounted for!’ They never did get any of it back. So Paul looks over at me and says, ‘John, I feel like eating some peaches, what do you say?’ I said no, because I thought they might do a surprise inspection, and I kept saying no for the next few days.

“The morning we landed on Iwo Jima, we were going over the side of the ship and Paul said, ‘I’ve got the peaches in my pack.’ I said, ‘Good, maybe we’ll eat them tonight.’ We got down on the beach and he said, ‘John, what should we do now?’ I never heard it, never saw it, but when I turned back to answer, he was gone. I finally found him at my feet, shot through the ribs. We’d been on the island less than a minute.”

“The morning we landed on Iwo Jima, we were going over the side of the ship and Paul said, ‘I’ve got the peaches in my pack.’ I said, ‘Good, maybe we’ll eat them tonight.’ We got down on the beach and he said, ‘John, what should we do now?’ I never heard it, never saw it, but when I turned back to answer, he was gone. I finally found him at my feet, shot through the ribs. We’d been on the island less than a minute.”

Lauriello named his youngest son after his deceased friend, but Paul says his father didn’t talk about the war for most of his life.

“He was 21 when he landed on Iwo Jima. He came home and just kept quiet about it for 40 years,” Paul says. “It’s really only in the last couple decades he’s been opening up a bit and letting people in on the story.”

Lauriello says the reason he didn’t tell many war stories was that there wasn’t much he remembered clearly and what he did remember was nothing short of terrifying.

“It was death from the sky,” he says. “They were firing from both ends of the island, right on top of us. You could see the trackers from the machine guns, and there were artillery shells exploding above your head. They were firing mortars – they were so accurate they could drop one of those in your dungaree pocket. There was so much noise – bodies and limbs everywhere. When you think back, you’re aware of transitions. I remember landing clear as day, and I remember leaving like it was yesterday. Everything between is a blur. I don’t remember eating or talking. All I know is when the battle ended, I was standing.”

The Battle for Iwo Jima is considered one of the bloodiest in Marine Corps history. An estimated 27,000 Marines were killed or wounded. The unlikelihood of his father’s survival hit Paul as he stood atop Mount Suribachi – where Joe Rosenthal snapped the iconic photo of Marines raising the U.S. flag – watching his son Talon on the beach below.

“You’re standing there, looking at that spot where he landed, and you realize there’s just no way they should have won that battle,” Paul says. “The Japanese had the high ground, they had every advantage. It’s a miracle anybody survived. You stand there and you look at that – really see it – and you start to think, ‘I’m not supposed to be here. My kid is not supposed to be here.’ It’s overwhelming.”

“You’re standing there, looking at that spot where he landed, and you realize there’s just no way they should have won that battle,” Paul says. “The Japanese had the high ground, they had every advantage. It’s a miracle anybody survived. You stand there and you look at that – really see it – and you start to think, ‘I’m not supposed to be here. My kid is not supposed to be here.’ It’s overwhelming.”

Talon, a freshman at Shawnee High School, missed two weeks of classes and state testing, but he considers his trip to Iwo Jima a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

“I was a little scared about missing two weeks of school, and I thought, ‘What’s the principal going to think?’ He actually agreed this was the trip of a lifetime, and that far outweighs school,” Talon says. “I realized this was way more amazing than anything in a textbook, and I needed to go. My dad and I kind of said to each other, ‘It doesn’t matter, we don’t care, we’re going.’”

While his father and grandfather looked on, Talon sprinted up the beach on the route Lauriello took 70 years ago. He says he gained a newfound respect for the actions of his grandfather and other veterans of the Battle for Iwo Jima.

“I was so moved,” Talon says. “It was so hard to run up that beach, I thought I wasn’t going to make it. Tons of people on the trip reminded me that the Marines who landed here weren’t much older than me, and that’s so insane. I can’t even come close to doing this stuff – putting on a 50-pound backpack, carrying a rifle and trying to keep it dry, all while being shot at? I don’t know how he did it.”

Though an annual commemoration ceremony has been held on the island for the past 16 years, this year marked the first time Japanese cabinet officials joined the American visitors. Lauriello was introduced to Tsuruji Akikusa, a Japanese man who’d survived the American invasion by hiding in underground tunnels and caves before eventually surrendering. The former enemies shook hands and spoke through an interpreter.

“Now that was emotional,” Lauriello says. “We talked for about five minutes, and I leaned over to his interpreter and said, ‘I want you to tell him that I consider the two of us to be the luckiest bastards on this island today.”

Lauriello’s voice sticks in his throat when he tries to talk about the men who didn’t come home from Iwo Jima. He says being back there was at times very painful, but also gave him some measure of closure.

“The plane we took to Iwo from Guam circled the island, and the first thing I noticed is that it’s so green,” Lauriello says. “The last time I was there it was this raw, bombed-out rock. It’s difficult to explain the feeling of having been there in the height of battle, and then to return and see that little island so lush and quiet. And then to be there with my son and my grandson – I just have so much to be proud of, so much good that’s come in the last 70 years. It just put me at peace.”