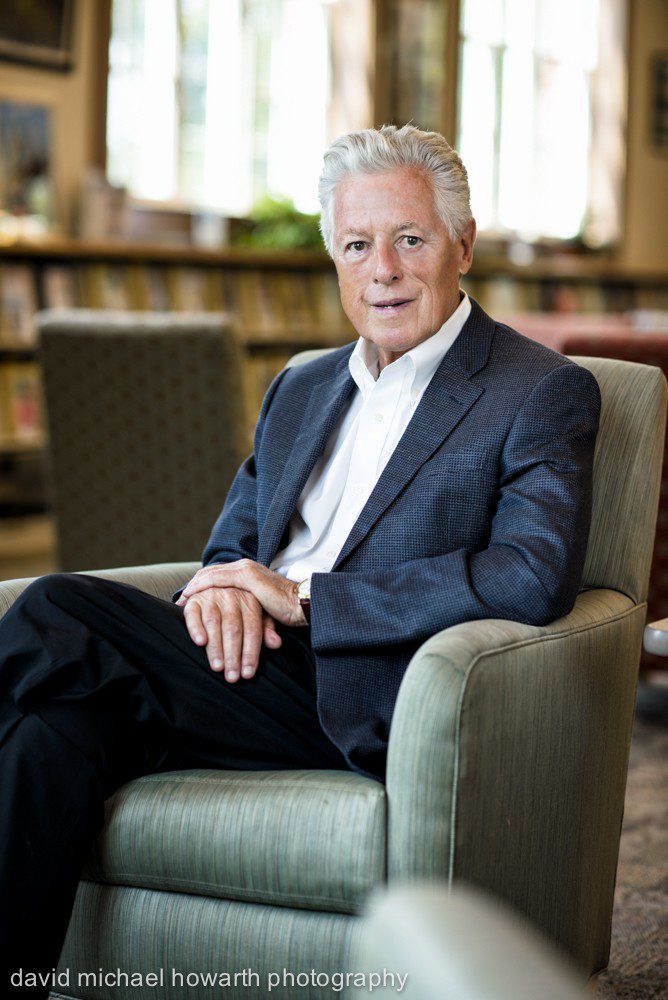

Photography by David Michael Howarth

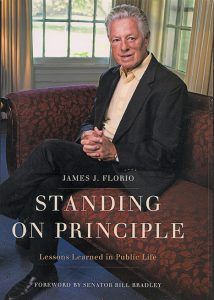

Former Governor James Florio has released his memoir “Standing on Principle,” which describes his career in local, state and national politics. Having served 15 years in Congress and four years as New Jersey’s 49th governor, Florio has a long list of stories, anecdotes and opinions to offer readers. His book is a personal account of political happenings many readers may remember, although not with the behind-the-scenes narrative only Florio can provide.

Former Governor James Florio has released his memoir “Standing on Principle,” which describes his career in local, state and national politics. Having served 15 years in Congress and four years as New Jersey’s 49th governor, Florio has a long list of stories, anecdotes and opinions to offer readers. His book is a personal account of political happenings many readers may remember, although not with the behind-the-scenes narrative only Florio can provide.

In the selected excerpt below, Florio describes his role in the well-known FBI sting called Abscam.

Then there was Abscam.

I was one of several members of Congress approached by a guy named Joseph Silvestri, who told me he represented a group of Arabian sheiks who were requesting my assistance. He suggested that I meet with the sheiks and some of their representatives in Georgetown. If I agreed to help them, he said, they would return the favor by helping me obtain funding for projects in Camden.

What really turned me off about this guy was how he bragged that he “owned” Congressman Rodino and Senator Williams. I knew that Harrison Williams had a drinking problem, and I worried that Silvestri might actually have something on the senator. But I also knew that Peter Rodino was above reproach, and I didn’t believe for a minute that this guy, or anybody he represented, “owned” the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. I wanted nothing to do with him or his sheiks, so I didn’t go to meet with them in Georgetown.

My colleague from the neighboring Second Congressional District, Bill Hughes, had the same experience. We talked about it later, about how this guy had approached us, and how neither of us wanted anything to do with him. But I thought later how easy it would have been to get ensnared in Abscam – which, it turned out, was an FBI sting. I might have taken the meeting if I hadn’t been so turned off by Silvestri’s brash and boastful attitude.

Yet I certainly wouldn’t have taken a brown bag with $50,000 in cash from the undercover FBI agents, as Congressman Michael “Ozzie” Myers of Pennsylvania did – for which he was expelled from Congress, convicted of bribery and conspiracy, and sentenced to three years in prison. But Senator Williams and New Jersey Congressman Frank Thompson of Trenton got “stung” in a different way.

Neither of them took a bundle of cash in a brown paper bag. Instead, they were convicted of using their office to further a business venture in which they had a hidden interest or otherwise aiding the Arabs (or, as it turned out, the FBI agents posing as Arabs) with certain immigration problems in return for money for projects in New Jersey. To this day, I am certain that alcohol played an outsized role in both

Senator Williams’s and Congressman Thompson’s downfall. I do not believe that either of them, had they been sober, would have betrayed the public trust as they did.

Back in New Jersey, Angelo Errichetti’s downfall wasn’t caused by alcohol: it was the product of sheer hubris. Serving as both mayor and a state senator at the time, he bragged to the undercover FBI agents that he could use the sheik’s money to get a gaming license for a group of partners in Atlantic City. He said he would use the money to grease the palms of politicians and state officials to ensure the success of the casino application – a boast that led to his conviction on bribery and conspiracy charges, removal from both his city and state offices, and a six-year prison term, of which he served thirty-two months.

“I can only blame myself for the tremendous ego I developed, the kind of ego that gets a politician into trouble,” Errichetti was quoted as saying on his release from prison. Earlier, having learned that I had spurned the overture to meet with the sheiks, he was quoted on tape dismissively referring to me as a “Boy Scout.” That is a badge I have always worn with honor.

Let me share one final thought about my fifteen years in Congress.

Washington has always been a partisan place, but it was not nearly as combative and divisive in the 1970s and 1980s as it is today. My primary interest was in accomplishing things for New Jersey, and that meant working with my Republican as well as my Democratic colleagues in the state delegation.

There were many issues, of course, on which we did not all see eye to eye. I sometimes found myself in profound disagreement with Republican congressman Ed Forsythe, whose district abutted mine and included large portions of Burlington and Ocean counties that fell within the Pinelands National Reserve. But we worked together to find as much common ground as often as we could. In 1989, I ran for Governor against another fellow Congressman, Jim Courter, and while that race was hotly contested, there were any number of issues on which we had earlier cast identical votes for the benefit of the citizens of New Jersey.

Our delegation came together to preserve the Pinelands; to clean up hazardous waste sites; to protect the Jersey Shore; and to provide federal aid to our cities, our schools, our police departments, and other institutions important to our state. I believe everyone in the New Jersey delegation can point with pride to the actions we took in those years, collectively, to benefit our citizens.

I had very cordial and mutually respectful relationships with Republicans

in the New Jersey delegation, on my committees and subcommittees, and across the aisle of the House of Representatives as we worked together on environmental, transportation, health care, and other policy issues. That, in large measure, is how and why we got things done in Congress in the years I spent there. In my judgment, the loss of cordiality and mutual respect is, regrettably, a major reason things do not get done today.