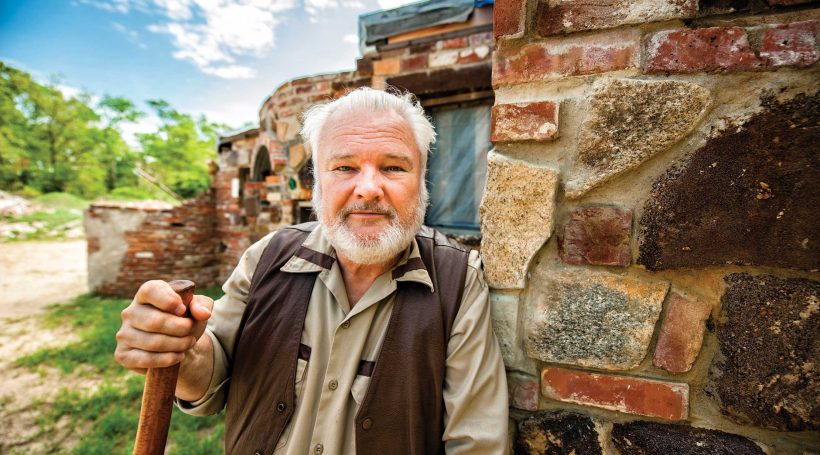

Kevin Kirchner is building a castle.

On Mill Road, just outside of downtown Vineland, there’s a nearly finished building that, at first glance, looks like an enormous pile of rubble. This is the Palace of Depression; a local legend, a community’s passion project and a monument to the man remembered as Vineland’s most intriguing resident.

In 1929, a man named George Daynor walked into town. He’d come on foot from New York City, having been left nearly penniless by the stock market crash. Before that, he’d lost his home in San Francisco to the earthquake of 1906, and before that, he’d made a fortune mining gold in Alaska. Or so he said.

“The first mystery of Mr. Daynor was who he was and where he’d come from,” says Patricia Martinelli, curator of the Vineland Historical Society and author of “The Fantastic Castle,” a book on Daynor. “I don’t think anyone will ever really find the answer. I tend to think he was really a builder from the Doylestown area, but how much of his other adventures were true, I don’t think we’ll ever know.”

Daynor used his last $7 to buy four acres of land, sight unseen. The parcel was a swampy junkyard, and Daynor owned nothing but the property and its contents.

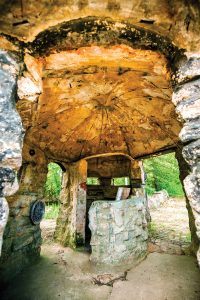

“He spent the first three years getting the land cleared,” Martinelli says. “Then he started to build. He laid a foundation and started to build walls out of concrete and car parts. He used everything he found in the junkyard. Pretty soon there were spires and parapets, he landscaped the grounds and had all kinds of weird statuary and things he’d found on display. It really wasn’t that big, but because of the underground rooms and the layout of the house, it looked much larger than it was. People thought he must be crazy. They’d periodically go over and ask for a tour, and he’d say, ‘Sure, it’ll cost you 10 cents.’ That’s how he got the idea to make it a tourist attraction.”

The walls were constructed with stones and bricks from demolished structures around Vineland

It worked. The Palace of Depression, so named because Daynor wanted to demonstrate that even those most affected by the economy could be successful, put Vineland on the map, drawing more than 250,000 visitors over the next two decades. In 1938, Daynor made a film about the park titled “The Fantastic Palace,” which was shown in theatres all over the country.

Daynor’s success hit a breaking point in 1956 when a young boy was kidnapped in New York. Daynor called the FBI and reported having seen the boy and his kidnappers at the Palace.

“When they found out he’d lied, that he was just looking for publicity, they threw him in jail,” Martinelli says. “While he was in prison, the Palace was ransacked by people who believed the stories that he’d hidden his Alaskan gold in the walls.”

Daynor died a pauper in 1964, and not long after, a fire destroyed most of the decaying Palace. Vineland bulldozed the rest in 1968.

“There were people who tried to fight the demolition. They tried to preserve it, but it was an uphill battle,” Martinelli says. “It was considered a nuisance, and it was razed.”

The land, which had fallen under ownership of the city, remained empty for 30 years. Enter Kevin Kirchner, a now-retired municipal building inspector.

“When I was working for Vineland, I’d have to sign off on every city-owned piece of property that came up for sale,” Kirchner says. “So in 1998, they were going to sell this piece of land to a developer to build housing. For whatever reason, I just couldn’t sign off on it. I kept putting it aside, and finally someone called me and said, ‘Hey, you need to sign for that sale!’ Right then, off the top of my head, I said, ‘I think I’d like to try to rebuild the Palace.’”

Kirchner gave a presentation to the mayor and council, and with 400 people committed to donating time or money and $12,000 already raised, the plan was approved.

“Most of that initial money was spent getting permits to build on the wetlands,” Kirchner says. “When we started it took two whole years to clear the land. It had turned into overgrown, dense forest.”

Kirchner wanted to replicate the original Palace, but all that remained was the ticket booth, a small, round cinderblock structure. Kirchner studied photographs and the film to learn how Daynor’s home was constructed, but it was Vineland native Jeff Tirante who turned it into a work of art.

Tirante, 56, is too young to have visited the Palace in its heyday, but he says he’s felt drawn to the property throughout his life.

The original ticket booth remains on the property

“When I was a kid, I watched what was left of the Palace being torn down,” the artist says. “They left the ticket booth, and at night we’d come out here and sit and play guitar. Little kids came and played here – it was their fairy castle. In 1986, it was my wedding chapel. Even if you didn’t know the real history of the place, if you grew up in Vineland, you have some memory of the ticket booth.”

At 65, Kirchner vividly remembers his own long-ago visit to the Palace and his encounter with Daynor.

“I came here with my family when I was 4 or 5,” Kirchner remembers. “I saw George Daynor with his white hair and his crazy beard, and I thought he was a werewolf. I had nightmares about this place for years. Funny, isn’t it, that I’d end up here doing this?”

Over the last 10 years, Kirchner and Tirante, with a team of a half-dozen regular volunteers, have painstakingly built what is not only a near-perfect replica of the original structure, but also a feat of engineering brilliance. Kirchner has constructed the rambling Palace entirely with salvaged parts, like the steel beams from a collapsed bridge that serve as supports for the first floor, while keeping the building in line with fire and safety codes.

“Daynor built it with car parts and things he found in the junkyard. Because I was a building inspector, it’s been easy to get materials. Every time a building got taken down, they’d bring everything here,” Kirchner says. “The only difference between the original castle and ours is that ours will be wheelchair accessible. We found ways to keep everything up to code. There will be electricity and accent lighting, but it’ll mostly be knob and tube wiring, which is what Daynor would have had.”

Like the original, the walls of Kirchner’s palace are embellished with scavenged odds and ends. Empty liquor bottles set into the mortar at eye level cast multi-colored light into rooms. A carved bird statue is cemented near the ceiling at the entrance; Kirshner and Tirante argue over whether it’s an eagle or a raven. The walls are dotted with colorful pieces of blown glass – the cast-offs of nearby Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center.

“We take a lot of their faults,” Kirchner says. “If they make something like a paperweight and it has a tiny bubble in it, they throw it away. So instead, we cart it out of there in five-gallon buckets.”

Other decorative items came from members of the community, who Tirante says often stop by the site with something to add to the Palace.

“When we first started, people would show up with a marble or a knick-knack of some kind and ask us to put it into the walls,” he says. “We’ve tried to find everything a spot in the wall, because that’s how Daynor built the thing. It’s really special that so many people have contributed the bits and pieces of this.”

Local artist Jeff Tirante has sleeping quarters on-site for night-guard duty

The finished building will be three stories high with a metal roof, and furnished with a collection of antiques and replica appliances and furniture. Kirchner says the Palace should be complete in 2017, and a visitors’ center on the property will be finished this summer.

“When I first presented the idea, I thought it would take three years,” Kirchner says. “Then the first three years, we’d build from April to November, and then kids would come out and knock down the walls we’d put up. But now we’re getting close.”

Once the Palace is completed, it will be open to the public year-round. For now, the only event the property hosts is an annual haunted house near Halloween. It’s not difficult, Kirchner says, to make the place seem spooky. While the rooms on the main level are airy and well-lit, there’s a natural air of the macabre in the underground rooms, where cramped tunnels shoot off into darkness. This is where Tirante spends a great deal of time – often sleeping on a cot in the small space. He’s the first line of defense against thieves, scrappers and vandals, and when local teenagers sneak in late at night, Tirante finds creative ways to dissuade them from coming back.

“I’ve had the most fun in my life being down here,” he laughs. “I’ve had kids come down at two, three in the morning, and they’re trying to look down into the tunnel. They have no idea I’m sleeping right on the other side of the wall. One kid will say, ‘Hey, give me the light, I want to see what’s down there,’ and I’ll sneak up behind them, strike a match and say, ‘Will this do?’ They’re pretty sufficiently freaked out.”

Tirante is quick to recount a number of inexplicable experiences he’s had in the Palace. He sees the occurrences as proof of a spiritual presence. Kirchner is more reticent, though he admits there are some things he can’t explain.

“I don’t believe in the paranormal. I never did,” he says. “But you know, it’s starting to get me. When we were laying the concrete foundation, we had this flash rainstorm come out of nowhere and flood everything. We had to send the concrete back and re-dig the footings. The next day, a chunk of concrete fell out of the side wall. I picked it up to throw it out of the hole, and on the other side was the date – August 1929 – and George Daynor’s handprint. If we’d poured the concrete the first day, I’d never have found that.”

Kirchner stops short of believing there are ghosts at the Palace of Depression, but he does feel George Daynor’s spirit lives on in his work. He certainly shares the same passionate dedication; since his retirement, Kirchner spends about 80 hours a week at the Palace.

“I think he was just a man who had a vision and wanted to build something special. I think that’s me, too. I didn’t really notice until my wife pointed it out, but she says I’m turning into him,” Kirchner says.

“What’s weird is I almost look like him; especially when I grow my beard out. I don’t think I meant for this to become my biggest project, but I guess I got hooked, and now I just have to see it through. I said we were going to bring the Palace back, and that’s exactly what we’re going to do.”