Laura Dern is known to step into a role and truly inhabit the characters she plays. That’s the only way to explain how the tall, blond iconic actress so convincingly pulls off the look and feel of a depressed suburban housewife in “Cherry Hill: A Childhood Reimagined,” a memoir by her close friend, photo- grapher Jona Frank. As Frank, a Cherry Hill native explains, Dern “becomes” her short, dark-haired mother in this unique work of art. But there was never any doubt that would happen.

Jona Frank with Imogene Wolodarsky, portraying a teenage Frank who’s almost afraid of the telephone, which always seemed to ring with bad news.

Laura Dern is not herself. The actress has just stepped into the southern California kitchen that her close friend, photographer Jona Frank, is using as a set. She’s in costume – a dark wig in a long bob with side-swept bangs and a sleeveless, floral button-down dress.

Laura Dern is not herself, but Frank recognizes her right away. She’s Rose, a Cherry Hill housewife, circa 1972, who fills her days with coupon clipping, baking, and the business of suburban motherhood. For Frank, it’s a jarring moment. The transformation goes much further than a vintage dress or hair and makeup artists alone could take it. Dern has become, even in near-invisible ways, Frank’s mother.

“She took on characteristics of my mother. Specifics I didn’t tell her to do,” Frank says. “Certain things she did with her lips – I felt like I was the only person in the world who saw my mother do that. A certain way she’d hold her shoulders, and I could look at them and tell her mood – Laura did all of that.”

“She took on characteristics of my mother. Specifics I didn’t tell her to do,” Frank says. “Certain things she did with her lips – I felt like I was the only person in the world who saw my mother do that. A certain way she’d hold her shoulders, and I could look at them and tell her mood – Laura did all of that.”

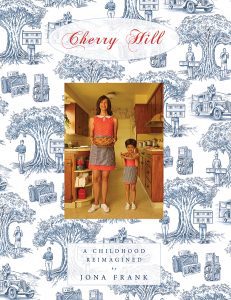

Frank’s new memoir, “Cherry Hill: A Childhood Reimagined,” blends photos and essays to tell her story of growing up in 1970s South Jersey – in a family that commended conformity – and realizing she didn’t exactly fit in. She wanted to be an artist. It’s a project Frank, a prolific portrait photographer with 3 previous books, has been developing and discussing for a long time, especially with Dern. The pair have been close friends for years – their sons, now both 19, befriended each other in preschool. Frank knew she wanted the photos to feel “as cinematic as possible,” so when it came time to cast someone to play her mother, she thought, “Why not have a screen icon?”

And Dern certainly is that. For more than 4 decades she’s been enamoring directors – Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Clint Eastwood and David Lynch – with a spellbinding onscreen presence and a face that is, as writer Christine Smallwood called it in a 2019 New York Times Magazine profile, “superelastic.” Her roles are all vastly different – she’s always chosen carefully, to avoid typecasting – they do tend to have some things in common.

Laura Dern portrays Frank’s mother as the quintessential 1970s homemaker who can’t always keep it all together. When she was in middle school, Frank writes, her mother began to periodically “shut down.”

“They’re often women struggling to find their own voices,” Dern said last year. “They’re women in completely different positions and moments in their lives, who don’t feel that the world has given them room to have a voice or opinion, or to matter.”

Those are characteristics Frank saw in her mother, and Dern’s innate understanding helped fuel the transformation.

“She doesn’t look anything like my mom,” says Frank. “My mom is 5’2″ – Laura’s tall and blonde. But I saw her in this movie “99 Homes,” and she’s a mother who’s extremely disappointed. There’s this scene when she walks across the room and she just looks like she’s falling in on herself, and I remember thinking, ‘She could play my mother.’”

Frank’s book is beautiful – awash in 1970s patterns and warm light – but its narrative is often painful. A young Frank agonizes over disappointing her mother, feeling responsible when “the bedroom door doesn’t open and it’s 2 pm, and you know something’s wrong. I worried about my mom. I think I learned that there was a certain amount of conforming I had to do to avoid upsetting her, to avoid setting something off that could lead to depression. But no one ever said the word depression.”

The cover of Jona Frank’s “Cherry Hill”

Frank chafes against the expectations of her community and her parents, who’d “found what they wanted, and satisfaction in Cherry Hill.” The memoir details what she considers her escape – first to college in Boston, then to California and a career in photography.

And this childhood story Dern is helping Frank tell is not a critique of suburbia, the photographer says. “I feel nostalgia about Cherry Hill. I did have to escape. I had to see a bigger world, a bigger picture. It’s a perfectly nice place to grow up, but I wanted to roam, wander. I wanted to drive around.”

A career in the arts seemed unconventional, at best, to Frank’s parents, but that wasn’t Dern’s experience. In fact, it was quite the opposite. Dern was in movies long before she was in movies, as the daughter of actors Diane Ladd and Bruce Dern. In 2010, she and her parents received neighboring stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

By the time she was a teenager, Dern’s talent and ambition were obvious. A 1986 New York Times story calls her “a teenager to take seriously,” and quotes then-19-year-old Dern wondering “what it would be like to have a normal childhood.”

But while it may seem that the 2 upbringings – Dern’s among her parent’s uber-famous friends in Malibu and Beverly Hills and Frank’s quiet suburban existence in Cherry Hill – took place on different planets, they shared more than it would seem. “I was raised very strictly by my mom and my Southern grandmother,” Dern has said. “There was no rebelling at home.”

For both Frank and Dern, the whole project is wrapped up in tangled threads of memory, nostalgia, dreams, disappointments, childhood and motherhood.

Patterned wallpaper symbolizes the family’s mundane routine

“If we’re trying to be authentic and present in our failings and our efforts as parents, the story of our own childhood comes up,” Dern told The New Yorker in a late 2020 piece about “Cherry Hill.” “I’m reevaluating the many faces of motherhood. These things that seem perfect, everything should feel great, but nothing is fun.”

Frank’s work has “all been about the notion of becoming,” she says. “What I did in ‘Cherry Hill’ was turn the camera on myself and say, ok, I’m going to tell you my story. All these years I’ve been asking people to allow me into their world to photograph and now I’m going to flip that toward me. These pictures to me are not about proof that something happened. They’re about memory, and creating a feeling with images of a time period. It’s a sense of looking in on something, watching my mother from outside. It’s not about Kodak moments; it’s about the record of our lives that we carry around.”

Throughout “Cherry Hill,” Frank’s photographs feature three actresses (Violet Settecase, Jaya Elyse, and Imogene Wolodarsky) who play her from childhood through her 20s. The story winds through years of Frank going through the motions of a safe, suburban routine – “dinner at 5:30, TV at 8, church on Sunday” – all the while feeling stunted and trapped.

In 1990, after college, Frank left Cherry Hill to see the world, and to photograph it. “It was all too much for [my mother],” she writes in the book’s final pages. “It was not her plan for me. She told me if I left and traveled it would ‘destroy her.’ I knew if I compromised who I was any longer, it would destroy me.”

Frank’s parents never left South Jersey, though they did move out of Cherry Hill. Her mother is 92, lives in Mays Landing, and hasn’t seen the book yet. Frank says it’s something she wants to show her in person, but the pandemic has kept the two apart. Frank wonders whether Rose will look at the images and see herself, or Laura Dern. Maybe it’ll be both.

With “Cherry Hill,” Dern and Frank have created – or at least advanced – a surprising new genre. It’s a cinematic narrative that unfolds one page at a time, honest and relatable, raw and the tiniest bit whimsical. The magic is in the interaction between Frank and Dern: the artist who lived it and the artist who brought it to life.