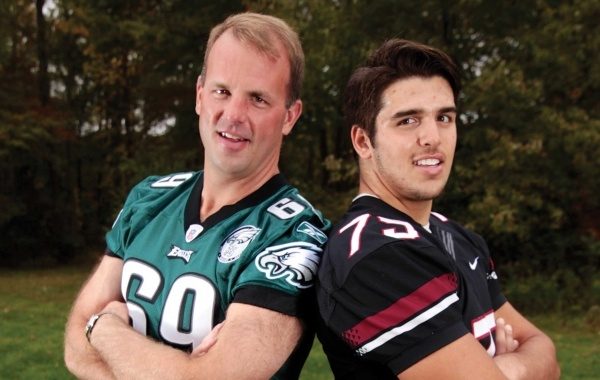

Young men often want to follow in their fathers’ footsteps. But what if your dad is a beloved NFL star-turned-congressman, or, say, a local legend who was portrayed on the silver screen by Mark Walhberg? Imagine the size of those footsteps.

Vinny Papale and Jon Daniel Runyan, sons of former Eagles players Vince Papale and Jon Runyan, are primed to represent SJ on the college gridiron next season.

Jon Daniel, a senior at St. Joseph’s Preparatory School in Philadelphia, has already committed to the University of Michigan, his father’s alma mater, where he will continue his burgeoning career.

“I remember growing up, Michigan was always a part of my life,” says the 17-year-old 6-foot-6-inch, 185-pound offensive lineman. “I’ve always been around it, and it’s always been in my head. I think it was pretty much my only choice.”

“I remember growing up, Michigan was always a part of my life,” says the 17-year-old 6-foot-6-inch, 185-pound offensive lineman. “I’ve always been around it, and it’s always been in my head. I think it was pretty much my only choice.”

Jon Daniel sees the university as an opportunity for athletic and academic success. But for his father, the school represented an escape from the difficulties of his adolescence.

“Football was a way to get out of the situation I was in,” the elder Runyan says.

“For my generation, growing up in Flint, Mich., as the auto industry was falling apart, things were pretty bleak. Your high school guidance counselors would tell you, ‘You need to find a way out of here, because you’re not getting a job in the factories.’ There were times when we were flat broke, we were on food stamps, we were closing off the second story of our house so we didn’t have to heat it, just to make ends meet.”

Runyan, who graduated high school at 6 feet 7 inches and 330 pounds, saw his physical stature as his ticket to a better life, but he had to work hard. As he saw his son beginning to develop the same physical attributes, he urged him not to depend solely on his size.

“I’ve always been one of the most athletic kids I know, and in grade school that gives you a false sense of security,” Jon Daniel says. “You know you’re better than everyone, but really that’s such a small percentage of the athletes you’re going to meet and play against. In high school, there are a lot of kids who are more athletic than me, but I’m more driven, and I work harder.”

Vince Papale says that for his son Vinny, a wide receiver and defensive back in his senior season at Bishop Eustace Preparatory School in Pennsauken, the athletic ability comes naturally.

“Vinny never has to worry about people making a comparison between him and the athlete I was at 17,” Papale says. “He is clearly the athlete in the family. He’s better than I was on so many levels.”

Jon Daniel says he tries to block out comparisons between himself and his father, who played 14 seasons in the NFL, nine of them with the Philadelphia Eagles.

“I just want to prove everybody wrong who says, ‘It’s all because of your dad,’” Jon Daniel says. “I feel like people think that all the time. I’ve worked just as hard or harder than everybody else. I think that’s paid off, and people are starting to see what I can do.”

Like his dad, the teenager hopes to join the NFL after Michigan. “It makes sense that he would follow my same path,” Runyan says. “I know all the pitfalls. I have all the connections, and I know who to talk to and what to say. It’s the same as a father whose son is following him into real estate. The father knows all the big brokers and has all the leads. It’s about connections, but it’s also about them. They have to want it.”

Runyan also wants to make sure Jon Daniel understands the risks of playing a grueling sport at the professional level.

“I say it all the time around him; you do that for a living and you’re making really good money, but every time you go out there you’re taking days off your life,” Runyan says. “I’ve had five major concussions in my life – who’s to say something neurological won’t happen to me? At what point do my knees fail or my back gives out? It’s like anything else in life – the more risk you take, the more you’ll be rewarded for taking it.”

Jon Daniel says that while he’d be honored to be drafted into the NFL like his dad was in 1996, he takes those warnings seriously.

“Always hearing these stories of players and the injuries they have, it makes you a little hesitant,” Jon Daniel says. “But of course growing up, playing in the NFL is what every kid wants to do. I’d really like to play at that level, but it would take some time and thinking to decide if I really want to. If I’m good enough, and I’m in a position where I’m offered that chance, I feel like I would, but I don’t feel I have to do it just because my dad did.”

Jon Daniel says he’s putting off thoughts of the NFL in favor of daydreams about getting to college, where modern technology and social media have given him a jumpstart on building a social circle.

“It’s going to be very comfortable because I already know most of the guys on the team,” he says. “We have a group chat on our phones and we follow each other on Twitter. You get to know your teammates, how they talk and respond to things. It’s nice because then when you actually meet them you understand them and know their interests.”

Vinny also dreams of playing professional football, but he plans to take things one step at a time. He was named to the prestigious U.S. National Football Team this year, and says playing with teammates from across the country has made him eager to join a college team. Vinny has verbally committed to University of Delaware to play for the Blue Hens. In February, he’ll sign a letter of intent in Dallas alongside his national teammates.

Vinny also dreams of playing professional football, but he plans to take things one step at a time. He was named to the prestigious U.S. National Football Team this year, and says playing with teammates from across the country has made him eager to join a college team. Vinny has verbally committed to University of Delaware to play for the Blue Hens. In February, he’ll sign a letter of intent in Dallas alongside his national teammates.

“The NFL is a dream of mine, but right now my ultimate dream is to play college football and get a great education,” Vinny says. “The education is so important to me, because there’s got to be a life after football. If the chance to play in the NFL comes, of course I’d love to. In the meantime, I want to study business and find out where that will take me.”

Vince Papale says he tries not to think about how soon his son will depart for college. For the time being, he’s just enjoying being a father and a coach.

“I’ve been his coach since he played Cherry Hill youth football,” Papale says. “When I was asked to be a volunteer coach here at Eustace, I said I had to ask Vinny first and get his permission. There’s a balance you have to find between coach and parent. He knows that when he comes home, whatever he did at the football field stays on the campus. This has been the best year of my life, and I love coaching, but I tell all the kids: ‘When I’m here, I’m the coach, but when I leave the field I’m just Vinny’s dad.’”

Though Runyan isn’t Jon Daniel’s coach in an official capacity, sometimes he can’t help but give his son a tip, or remark on a misstep Jon Daniel made in practice. The younger Runyan says this doesn’t bother him – he sees it as an opportunity to get better.

“It’s a helpful thing,” Jon Daniel says. “It’s another set of eyes, and someone who can tell you what you did wrong and what you have to do to fix it. He tells me those things, but he doesn’t put pressure on me. The pressure comes from myself and my team. I put pressure on myself to do my job, so I don’t let anyone down, especially not the person I’m playing next to.”

Runyan says he plans to see as many Michigan games as possible next season, and he’ll continue to point out Jon Daniel’s missteps – infrequent as they may be – and support his son in every way.

“After my sophomore year at Michigan, I started taking stuff for granted and doing stuff like not showing up for off-season workouts,” Runyan remembers.

“The strength coach pulled up next to me when I was walking down the street and said, ‘Get in the car, we need to talk.’ So he took me to his office and sat me down, looked me in the eye and said, ‘Listen, if I told you that you were going to win the lottery in the next two years, and all you needed to do was walk down here every day and buy a lottery ticket from the corner store, would you do it?’ And I said, ‘Of course I would.’ And he said, ‘Then get your ass in this weight room every single day.’ I was fortunate to have the right people around me at the right time to set me straight, and if [Jon Daniel] ever needs that from me, I hope I’ll be there at the right time.”

College athletes are celebrities on campus, but for Jon Daniel and Vinny, being recognized on the street is nothing new. Their famous fathers have prepared them for a life in the spotlight. Vince Papale is now an author and public speaker, and Jon Runyan just left the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served from 2011 to 2014.

“I don’t try to be the center of attention, but you just learn to deal with it,” Runyan says. “When I started running for office, people asked how my kids would deal with it, and I said, ‘My kids will be fine. Eagles fans are far more vocal than any political opponent in South Jersey will ever be, and their peers at school know way more about football than they do about politics. They’re used to it.’”

Jon Daniel says he’s aware of his place in the public eye, and as his star rises, he plans to maintain his integrity, along with his public image.

“I think today we put people like celebrities and athletes on pedestals and we cherish them, but as soon as they do something wrong we tear them down,” Jon Daniel says. “That makes people who don’t like what they’re doing with their lives feel better. People are always looking for something to get you in trouble with, so I just don’t get involved with anything I feel isn’t good for me or could put me in a bad position.”

Vinny first felt the heat of his father’s spotlight as an 8-year-old, when the movie “Invincible” hit theatres in 2006. The film told the story of Papale’s journey from Philly kid to a walk-on Eagles wide receiver.

“There was a lot of attention brought on by the movie,” Vince says. “It was mostly good and mostly positive, but it wasn’t always a great experience for the kids, because of other people’s jealousies and insecurities. Vinny and his sister Gabby are so successful, in the classroom and athletically, sometimes people say, ‘Oh, they’ve got the edge, because someone made a movie about their old man.’ Vinny wrote about that for his college essay, and I was so proud. That kid is his own man. He has his own identity, and everything he’s ever done he’s done on his own. He gets out on that field, and I’m not there. He’s out there on his own, doing the work.”

Vinny is aware of the attention his name brings, and while he feels he has a responsibility to that name, he also tries to make his accomplishments and abilities his more noticeable traits.

“I do feel like because of my last name, I’ve always had eyes on me, and everyone knew who I was,” Vinny says. “I know how to respect my name, and how to carry myself. I know people are watching. I know what I have and what I could lose. I just go out and play, and I’ll keep going out there, and keep playing and just keep being who I am.”

“Vinny’s mother and I have pushed all the right buttons, and now we just let it run. We sit back and listen to the engine purr,” says Vince.

Jon Daniel doesn’t have any reservations about the next chapter of his life either. Full of youthful optimism, he’s eager to carve his own path.

“I feel like if I just keep doing what I’m doing, I don’t have to worry about anything, and it’ll all fall into place,” he says. “I’m excited to get up to Michigan in less than a year and start playing ball. I just want to be the best that I can be. If you’re not trying to be the best at something, there’s no point to doing it. I’m proud of myself and what I’ve done, but I’ve got a lot more to do and a lot more to accomplish. I’ve only lived a very small portion of my life.”