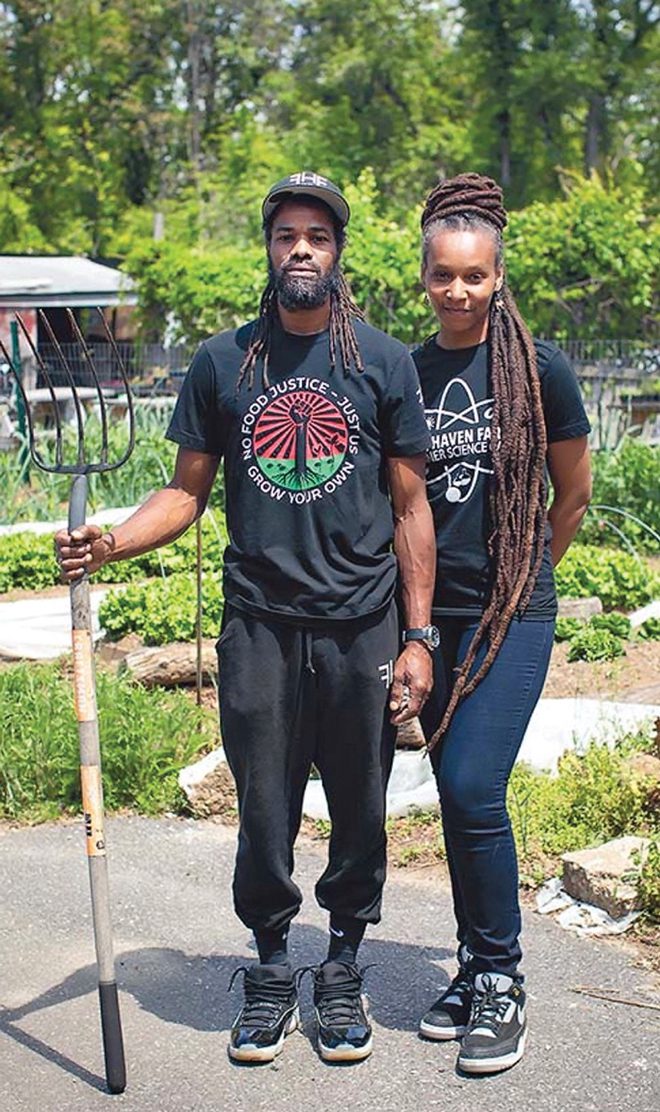

Photography by Clay Williams

It began with a grocery bill.

Lawnside native Dr. Cynthia Hall and her husband, Micaiah, were living in Atlanta while Hall finished graduate school at Georgia Tech. When they had their first child in 2006, eating healthy food suddenly became a priority. “We were a young family, and Micaiah was working, but between the mortgage and a baby, we didn’t have a lot of money,” Hall says. “Organic produce was really expensive, and we were trying to figure out where we could cut back to survive. That’s when Micaiah suggested, ‘Hey, I can grow some of this food we’re buying.’”

Soon, a small garden in their backyard was feeding not just the Halls, but their friends and neighbors. When Hall finished her degree and the couple relocated to Philadelphia for a professorship at West Chester University, the garden moved too.

“At the place we lived in West Philly, he put a garden in our front yard,” Hall says. “I entered him in a city garden contest through the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society – I didn’t even tell him. He won first place and had to go get honored and get an award, and for him that was really the switch that changed gardening from a hobby to more of a passion and career.”

“At the place we lived in West Philly, he put a garden in our front yard,” Hall says. “I entered him in a city garden contest through the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society – I didn’t even tell him. He won first place and had to go get honored and get an award, and for him that was really the switch that changed gardening from a hobby to more of a passion and career.”

He became manager and, eventually, director of a farm in Philadelphia. Hall, whose work in geochemistry meant plenty of study on soil and sediments, developed similar interests.

“As a professor, I was incorporating urban agriculture into my research,” she says. “We were getting interested in providing access to fresh fruits and vegetables, especially for communities that don’t have access. Once we moved to Philly, we saw a different part of the food system that we didn’t really experience before, and that’s where the mission part came in. That’s when we decided, hey, let’s start our own farm.”

In 2015, the couple began looking for the right property in Lawnside. They found it on Williams Street: a one-acre plot that needed plenty of work, but offered the space they needed.

“My family’s been there – I’m fourth generation in Lawnside – so it was really important for me, especially, to come back and do what we’re doing there. In 2017 we officially started Free Haven Farms,” says Hall. “We named it after the original name for Lawnside – Free Haven – based on its history as a stop on the Underground Railroad, and being a haven for African Americans trying to start a new life. That was like a metaphor for us trying to grow food and provide this access.”

Once things got growing, the farming couple took their produce to local farmers markets, and launched a CSA box program. They partnered with a farm in Pemberton, leasing five more acres to grow on.

Once things got growing, the farming couple took their produce to local farmers markets, and launched a CSA box program. They partnered with a farm in Pemberton, leasing five more acres to grow on.

As part of the wider mission to reconnect the community with their food, Free Haven launched a series of regular workshops on the Lawnside farm.

“People can come and learn about different topics within gardening,” says Hall. “We do soil workshops, workshops on planting, on harvesting; it’s a lot of listening to people about what they’re interested in learning about. Like last year, we had a specific workshop on growing watermelons, and we did a seed-saving workshop.”

During the pandemic, the workshops moved online, and Free Haven reached an audience all over the world. “That really opened up our impact,” Hall says. “We’ve had students from various countries on our Zooms, and that’s been very cool.”

One of the even bigger community impacts, Hall says, comes from Free Haven’s summer camps (hosted on the farm, for kids 5 through 12) and work with high school students. Hall, now a professor at Rowan University, also brings in interns from the college.

“In particular, we work with the Camden city school district,” she says. “It’s been really cool to meet people where they are and just introduce different aspects of gardening, environmental science, nature – all these different things we think are important for students to learn about and just to be more in touch with, especially now that they don’t have as much interaction with nature. It’s important to do these programs to just keep that connection. A lot of people don’t have experience being on farms and understanding the process of where our food comes from, because our food is just becoming more and more processed.”

“The kindergarteners, they run outside. They want to be out there. That connection is in them early. But by middle school, you have to coach them through it. But it’s a beautiful thing to be able to cultivate that.”

In addition to the impact of seeing how their food grows, Hall says she sees a big change in kids who spend most of their time in an urban environment. “It’s been really cool to see during summer camp, when kids are there every day for a week, how they grow,” she says. “Certain kids, at the beginning of the week, they’re literally screaming and crying because of a beetle. By the end of the week, well, maybe they’re not the one holding the bugs, but at least they’re not crying anymore.”

The younger her campers are, Hall says, the more comfortable they seem spending time outdoors. The farm’s programming focuses on helping older kids rebuild that passion once it’s been lost.

The younger her campers are, Hall says, the more comfortable they seem spending time outdoors. The farm’s programming focuses on helping older kids rebuild that passion once it’s been lost.

“The kindergarteners, they run outside,” she says. “They want to be out there. That connection is in them early. But by middle school, you have to coach them through it. But it’s a beautiful thing to be able to cultivate that.”

After all, she says, some of the biggest physical and psychological benefits come from simply spending time in a place where things are growing.

“Right now, we’re focused on Camden, but we know this work is needed everywhere,” she says. “Even in suburban areas where we have yards, you don’t see kids playing in them as much. And we’re losing green spaces, even in the suburbs, because there’s so much development. The little bit of nature we have left in these small towns is disappearing, so it’s more important than ever to be able to get more kids out to the farm.”

With the help of young interns and campers, and a small staff that includes their three children (ages 18, 16 and 13), Free Haven Farms produces an incredible amount of produce: enough to fill about 500 food boxes each week to be distributed by the Food Bank of South Jersey to families in need across Camden, Burlington and Gloucester counties.

“This is really where we see our work needed,” says Hall. “They’re able to get these boxes we put together – the same CSA box our customers purchase – at no cost. We want our work to be directed toward folks who don’t have access. We’ve been growing with that in mind: this is who we’re growing for, and why we’re growing this food. It makes it that much more meaningful.”